A 100 Muses

A conversation with Tarantula: Authors And Art's Inspiration for May, Dragana Jurišić

Dragana Jurišić is a Dublin-based visual artist whose long-term relationship with photography began with a loss. One Sunday evening in September 1991, during the war in Croatia, her family apartment in the small town of Slavonski Brod burned down, along with all the prints and negatives her father, an ardent amateur photographer, had accumulated. The next day he took his camera for the last time to document the damage caused by a shell that landed on their building.

Where her father left off, Jurišić continued, finding her inspiration in that triangle of photography, memory and identity. This was triggered by the loss of personal memory encapsulated in those burned photographs as well as by the loss of identity with the dissolution of the country in which she was born.

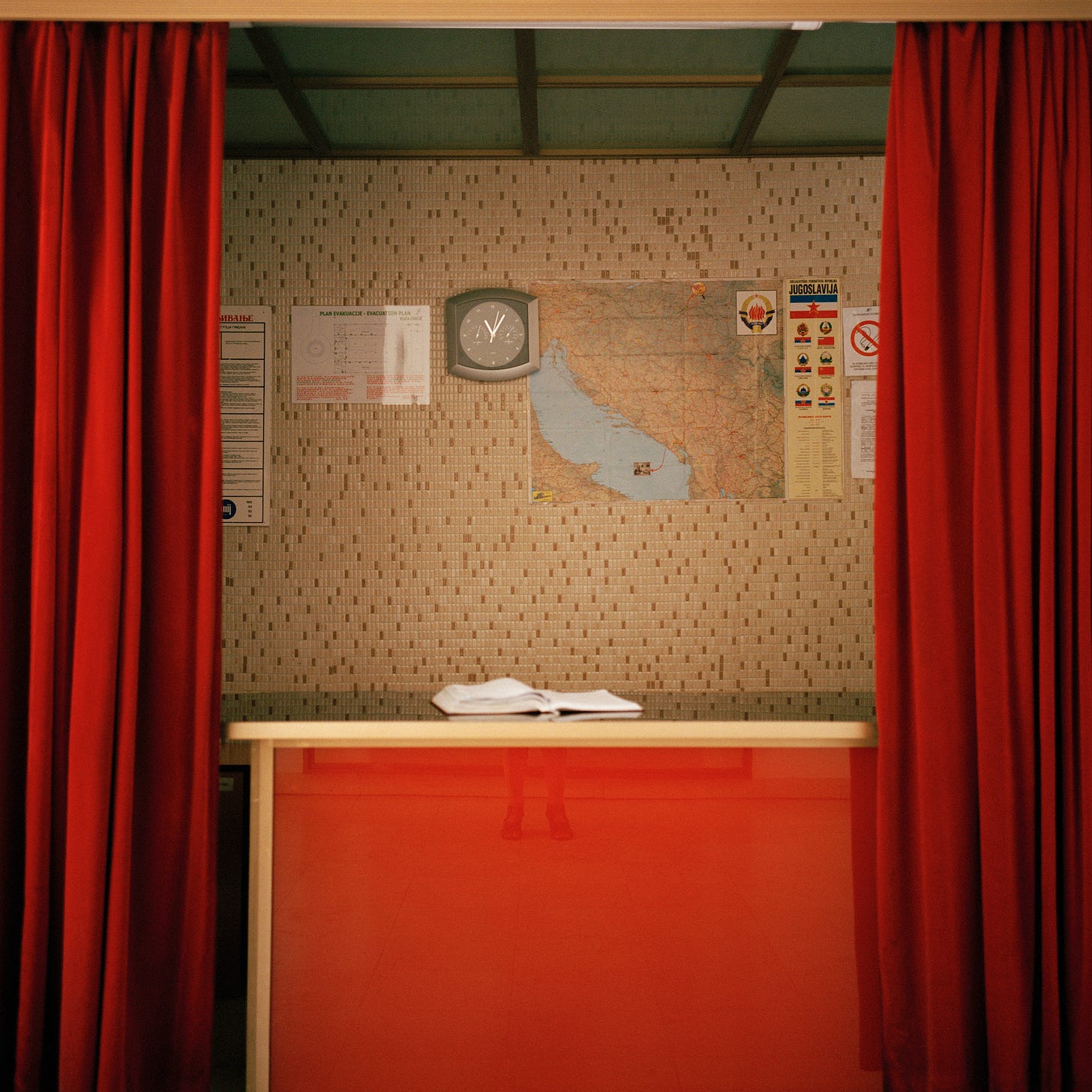

Her successful project YU: The Lost Country addresses that lost identity by attempting to re-examine the conflicting emotions and memories of the once-existing country. Using Anglo-Irish writer Rebecca Westʼs acclaimed book Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941) as a starting point, Jurišić embarks on a two-year-long journey retracing Westʼs steps across former Yugoslavia, re-living her own memories and re-interpreting Westʼs impressions through photography and text.

Yugoslavia remained a great source of inspiration for Dragana Jurišić. In one of the chapters in her new book, Her Own, just released last December in the Photo Museum of Ireland, Jurišić reconstructs the story of her aunt Gordana Čavić who fled rural Yugoslavia in the 1950s in search of freedom and a glamorous life in Paris. The mystery surrounding Gordana Čavić involves false identities and espionage.

The book's third chapter is dedicated to female muses, and since Muses are the topic of Tarantula: Authors and Art’s first printed edition, we chose this remarkable work for our cover.

In contrast to the cliché female nude that pervades the history of art and photography dominated by male artists, Jurišić invites women to pose and participate actively in this exchange between the artist and the model. Women were given two props, a chair and the veil, and they chose how to pose, which image represented them and whether or not their image was published at all.

Sandra Vitaljic: Could you share with our readers about the 100 MUSES production process and how it affected the women who took part as well as yourself?

Dragana Jurišić: The 100 MUSES chapter started as an experiment which evolved into an unexpected, two-way therapy session, which was more fortifying to me personally than anything else I had done before or since. I photographed 4 to 5 women a day, during a period of five weeks. I am not sure why I condensed this experience as much as I did, but it all made sense in the end.

At first, I didn’t have a strategy. It was the first volunteer who pointed me in the right direction. And that was to give the women both directing and editorial power. I was nothing more than a camera. The women chose how to move in front of the lens, and they chose the image that will represent them in the world.

At the same time, and this is the part I haven’t anticipated, the topics that the women talked about during the session, were heartbreaking. The amount of self-criticism and self-judgment, particularly directed to their own bodies, sometimes to the point of hatred, was very sobering. The stories of pain inflicted upon the bodies some of the women were also as battlegrounds, with wars waged harrowing, ranging from rape and domestic abuse to stillbirths and miscarriages. Women’s bodies as battlegrounds, with wars waged both internally and upon them. The resilience and strength that takes to survive these kinds of traumas is astounding.

As a result of having over 100 women mirror back to me my own experiences; I now have a new admiration and compassion for my own body and its strength, for which I am very grateful. Many of the women who took part in the project, reported to have had a similar experience. In some way, participating in the project made us realize that we can, at the very least, control what we think and feel about our own bodies and offer ourselves some kindness and grace.

In your work, you are often drawn to female characters that refuse to conform, such as Croatian writer Ivana Brlić Mažuranić or your own aunt Gordana Čavić whose mysterious story you are tracing in your book Her Own. Could you please tell us more about it?

I am drawn to women who want to be free. Sometimes they pay a high price for it. Ivana Brlić Mažuranić, for example, battled with herself to the point of suicide. Married at 18. Seven children. Four Nobel nominations. She wanted to write and create, which contradicted her conservative view on what meant to be a respectable wife and mother, at the turn of the 20th century. At fourteen, she wrote in her diary:

“For now, you should know, my plan is to become something." (...) You enjoy your semi-life. Vegetate and be! I am not giving up. I will not give up. I want to live. I want to make. Not make with a cooking spoon or a needle because I have no interest in that. I want to do something useful. I want to escape that sad life.”

Half a century later she wrote:

"I want to, and have to stay at home, because I lived from my 18th year to 64th for it, for my children, for my husband, for the idea of a family, just like any other honest woman. My literature, that favourite pastime of mine, was done secretly, away from others, taking one hundredth of my time. I believed so much in the complete duty of a woman to dedicate herself till the end to her home!”

This was the year she hanged herself in the attic of Zagreb’s sanatorium.

Gordana Čavić, on the other hand, did not care for appearing respectable. She put everything on the line to escape the oppressive existence of a farmer’s wife in the 1950s Yugoslavia. Gordana Čavić, an uneducated girl from a small Slavonian village somehow clawed her way to Paris. But they got her there. She was never able to truly escape.

How do you see women today; do we still face similar challenges, caught between the other people’s expectations and our own creative urge?

Yes. The types of challenges vary depending on where you live, but they do exist. Some women are fighting for basic human rights, survival for themselves and their families, for body sovereignty. The ‘war’ is waged upon them. Once that battle is over, as in some Western counties, the war shifts to internal geographies. The rise in cases of body dysmorphia, eating disorders and general mental health issues, in our digital age, is evidence for that.

Why are you drawn to nameless female characters like L’Inconnue de la Seine?

For your readers who aren’t aware, l’Inconnue de la Seine was the name given to a young woman whose body was allegedly recovered from the river Seine and whose death mask was cast in an attempt to identify her and as well as that, to preserve her beauty. The death mask inspired artists such as Man Ray, Albert Camus, Anais Nin, and many others, who projected their imagined identities on mass-produced piece of plaster. I was drawn to L’Inconnue de la Seine for similar reasons, she is a tabula rasa, a blank page on which you can project any identity to serve your story. However, in my latest book HER OWN, I attempted to give her a voice with agency.

What connects l’Inconnue de la Seine and Gordana Čavić?

What connects l’inconnue de la Seine with Gordana Čavić is, and this is of course, in l’inconnue’s case, based on alleged events, that these two women arrive to Paris from provinces in their youth, one decides to end her life because she does not want to live it in a way that was forced upon her, and the other, Gordana Čavić, does everything that’s in her power in order to survive. It’s the tale of two paths.

Have you discovered any traces of collective identity while traveling through what was once Yugoslavia?

That was a difficult journey. A little grey, but mostly black and white. Our collective past and identity were either demonized or idealized. Yugoslavia exists in memories of people, but we all know how unreliable memories are. Like compressed jpgs. Each time you retrieve the memory it loses information and is slightly restructured and changed. I guess the politicians who came to power after the civil war(s) were successful in achieving what Dubravka Ugrešić wrote about in her book The Ministry of Pain (2008): “With the disappearance of the country came the feeling that the life lived in it must be erased. The politicians who came to power were not satisfied with power alone; they wanted their new countries to be populated by zombies, people with no memory. They pilloried their Yugoslav past and encouraged people to renounce their former lives and forget them. Literature, movies, pop music, jokes, television, newspapers, consumed goods, languages, people - we were supposed to forget them all.”

How was this piece received by the global audience?

The work was received very well. It has been touring internationally since 2013. Everywhere I showed the work, people drew parallels. The first exhibition took place at Belfast Exposed in December 2013. The identity struggles in Northern Ireland are known to most people, so it’s not surprising that the work was well received. It received a similar reception in Barcelona. Many people from the ‘old country’ visited the exhibitions in Australia, Italy, Sweden, Holland, etc. and wrote letters and emails about their own memories of Yugoslavia. The only negative experiences were from anonymous trolls who left comments in The Guardian(which they had to shut down after an hour); and in Croatia’s daily Jutarnji List. None of these people had ever seen the exhibition or read the book. Merely using the word ‘Yugoslavia’ incited hatred.

What has brought you to Ireland? What object have you taken with you from 'home'? I am referring here to your work Something From There, which you created in collaboration with the National Gallery of Ireland and asylum seekers in Ireland to explore the notion of home and examining the significance of personal objects brought with them.

I came to Ireland to visit friends with whom I lived with in Prague in the late 1990s. Soon after, I fell in love with the people and decide to stay. I brought a heavy leather-bound Bible and a large pair of scissors with me. To this day, I do not understand why the Bible – religion was never my thing. Perhaps, it was a bargain with God; please let me live, and I will be a good person?” Still working on it.

Do you remember how it felt when you first arrived to Ireland? What presented the biggest challenge? How long did it take for you to feel at home in the new place?

I discovered how little border guards valued Croatian passports. It was 1999, and Ireland was experiencing an influx of immigrants. I suppose for a small island nation where people tended to leave the country in large numbers for various reasons, they did not know how to react at this reversal. Feeling unwelcome was usually restricted to the airport’s passport control area. If anything, this country, and its people have been exceedingly welcoming to me, and I am so glad that this is my home now. I was surprised to feel a sense of pride the year I got my Irish citizenship which I had never experienced before. I guess this place is a place I chose, whereas the other one was bestowed upon me by birth. Having said that, being born in Yugoslavia provided an endless source of inspiration for my work. How quickly this country disintegrated, how brightly it shone in its heyday, how bloody the end and its reverberations. It’s akin to experiencing, first hand, some kind of historical super nova explosion.

Is Dublin your home now? How do you feel about that?

Dublin is my home. I love the quiet. I love the chats. It feels safe. There is a lot of air here. Sometimes the wind brings an aroma of roasted barley from the Guinness brewery which is close to my house. I can feel the sky. The weather, you become used to it, after a decade or so.

In your work YU: The Lost Country, you are dealing with history, memory, but also personal identity formed in Yugoslavia, the dissolved country where both you and I were born. What impact does this have on who you are today?

I still identify as an ex-Yugoslav. I was born in Yugoslavia, to a Serbian mother and a Croatian father, where I spent the first 16 years of my life until the country was dismantled in a series of bloody wars. Today, it suits me to be a citizen of disappeared country. It has a fairy tale feel to it. As if I am a citizen of Atlantis.

It is clear that you draw lots of inspiration from literature, from Rebecca West, Henrik Ibsen and W.G. Sebald to Paula Meehan. How does literature influence photography? How did you choose photography as your artistic medium?

I learned to read by reading graphic novels and comics, so I would say that ‘image + text’ is a natural way of expressing myself. What fascinates me, is the emergence of the third language when images are juxtaposed with words. Literature has always been more inspiring to me than visual art. Of course, there are many aspects of visual art that I love, and I admire the works of many photographers, but I rarely look to it for inspiration.

Your work often combines images, text and video. How do you present it in a gallery space?

I like to play with installations, creating a world that speaks to a space, both its architecture, and its context and meaning. In the last seven years, I worked with an amazing curator, Natasha Christia, who spends a lot of time getting to understand the work, where it’s being shown and to what purpose, rather than simply creating an installation that conforms to current trends. I learned a great deal from her.

Some of your works are divided into chapters. Is a photo book a more intriguing way to present your work? Is your approach to composing a book different than setting up an exhibition?

I always think in the form of the book, which is why I need help with exhibition planning, design, and installation. It is important to work with talented people who can translate your vision into a three-dimensional space.

In one of your previous interviews you said: "Photographs are important in the creation of self-narratives." Could you elaborate on that thought?

Well, there’s a photo in your identity documents, not your thumbprint. When I was 16, my house burned down. Along with the house, all of my family photographs went up in flames. I barely remember anything that happened before that event. I discovered then the power that photography has over memory. Photographs stand in for memories, they help us recall our past experiences, they serve as physical evidence of the past.

That triangle of photography, memory and identity is constant source of inspiration for me.

What are you working on right now?

I am making a movie about a cult hero, Hari Džekson, a Yugoslav Western director who used local people as actors during 1970s and 1980s. Hari Džekson, was ethnically Albanian Muslim. He disappeared from the public eye in 1992, when his town of Bijeljina was attacked by Serbian paramilitaries. According to the urban legend, Hari Džekson went to defend his town singlehandedly, dressed as a cowboy, riding a horse, shooting with fake colts at the approaching tanks. My intention is to uncover what really happened to him. And a lot more. The film is about the love of process rather than outcomes, about self-mythologizing, about inserting oneself into historical narratives, and about the fallibility of memory, especially in a place that is still traumatised from the war, thirty years later.

You can find out more about Dragana's work on her website draganajurisic.com and her Instagram @dragana23