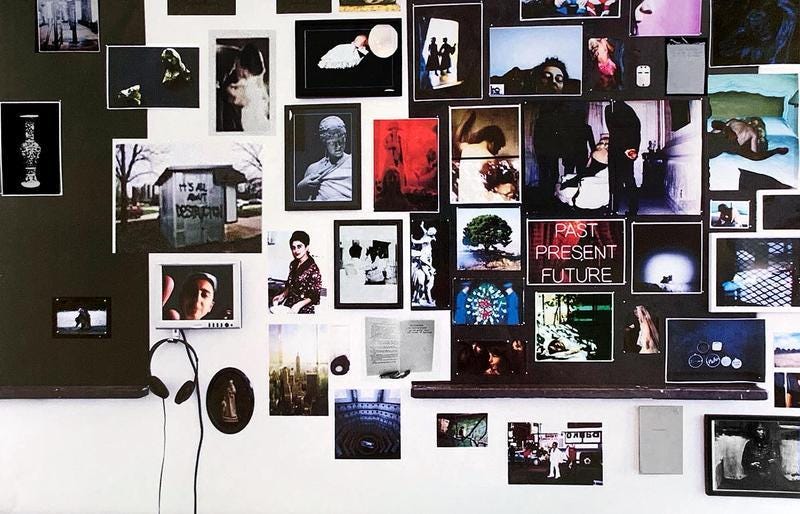

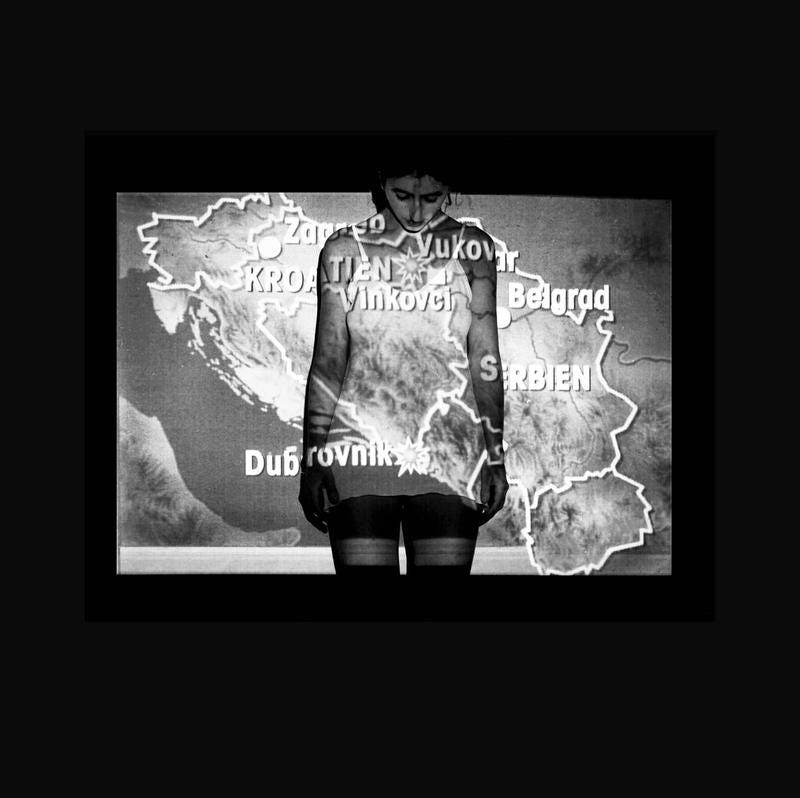

If you are a regular or have just discovered Tarantula: Authors and Art, welcome. Snezana Vucetic Bohm, a Yugoslav-Swedish artist, is our April inspiration. Her use of self-portraits in photography to understand her own identity prompted our writer, Lidia Oshlyansky, to search through her own family albums for answers to who she is and where she comes from. It isn't so simple.

If a friend forwarded you this article, welcome; if you like it, share it or why not subscribe?

“Where are you from?”

I hate that question! I’m American. Sort of. I sound it. I have a passport, a history of schooling and friends and homes and people from Ohio and Illinois, swag with university logos, yearbooks from high school. With that hair in my senior yearbook picture, only the Gods might understand why I cut it that way and agree with me that identity isn't always that easy to define. It’s not always a clear cut, one word answer and for many of us it includes multiple places, multiple experiences and multiple loyalties.

When I look at old family photos there are distinct eras. There are the mostly black and white photos from before I was six and the colour photos from then on. The old black and white photos are distinctly not American.

Black and White Photo:

A chilly, misty, autumn day in central Moscow. People with their warmer coats and some big fur hats. A petite elderly woman walks through the crowds leisurely with an excited little girl.

It's 1978, my grandmother Maria and I are visiting Moscow from our home in Kyiv to see my uncle Garik (Gary in later years, after he’d moved to the US). It's just months before we will immigrate to America and leave behind Soviet controlled Ukraine. It is our last chance to see him and his family for what will prove to be 10 years.

As we stroll through the crowded streets of Moscow I notice something yellow on the sidewalk. A bright spot of colour in the grey.

BANANA!

I’m 5 years old and elated. (think Minion excitement here).

Grandma, there are bananas!!! We must find them!

As a 5 year old Ukrainian (Soviet) kid, trust me when I tell you, bananas were very important and special because they were a scarcity in Soviet era Kyiv, and as they were all over the Soviet Union.

What follows are several hours of wandering the autumn streets, shop to shop, My poor grandmother forced to shlep the Moscow street in a fruitless search of the mystical shop that had the bananas. We never found them.

Black and White Photo #2:

An inconsolable, crying child returns to her uncle and aunt's house. Once there, several adults will listen to the search for bananas being cried out. They will ply me with the second best to bananas Polish chocolate covered plums which were also scares but more find-able at the time. I will play with my young cousins, be allowed to watch cartoons and go to sleep with, you guessed it, bananas on my mind.

First Colour Photo:

Autumn 1979. Bananas are everywhere. Every grocery store, every convenience store, every school cafeteria has them. They are cheap (99 cents a pound), they are in every state of ripeness, you can have them anytime you want. They are in fact an encouraged healthy snack given to every American kid at any time of day. I am now one of these lucky American kids.

Colour Photo #2:

I eat two, three, four bananas a day if I can. By age 10, I don’t want to eat bananas ever again. I’ve overdosed on bananas. I’ve turned completely anti-banana. It will take me another 8 or so years to eat them again and then only because they are the most “grabbable” item in the university cafeteria and come in their own handy wrapper (peel).

I still have a rather ambiguous or even ambivalent relationship to the fruit.

I am American, proudly so and yet these early stories from Ukraine are intrinsically part of me and how I think of myself, the little girl obsessed with bananas, or their scarcity. I am proudly Ukrainian, maybe especially so in the last couple of years as the horrors of Russian invasion pervade the news. There are several banana stories. American friends find them amusing and silly but there is no relatability to them. Recently I was mentoring a young Ukrainian designer who works for a company that makes health and fitness apps. We got on the topic of eating habits and how they differ by culture, age etc. Somehow I end up telling him one of my banana stories. He burst out laughing “my mom has a story that sounds just about the same! Were you two friends!?” His mom is my age and like me grew up in Soviet era Ukraine. She would completely identify and relate to my banana stories.

So, do my banana stories make me more Ukrainian? Does my absolutely ridiculous 80s hair, as featured in my highschool yearbooks, make me more American? Does the fact that after many years in the UK I write / spell in British English make me somehow less American?

So when people ask me where I’m from, my brain goes through a series of steps, I say “how far back do you want me to go?” Well like many other people on the planet I was born in one country (technically it no longer exists, because back then Ukraine was firmly in the hands of the Soviet Union). I grew up, and spent all my formative years from age 6 to age 30 in another country, the US. I spent years in the UK (just over 8) and I’ve spent the last 12+ years in Sweden. So, where am I from? Who am I? I feel very much me, and am completely secure in my own sense of “me”. I just find it occasionally tough to explain it to others who are much more firmly rooted in one place and one loyalty.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, like so many in the Ukrainian diaspora, I was devastated. My friends Elena and Katia took me to brunch on day 3 and just let me cry and cry and cry. They were also from various places in the Soviet Union and like me, left as children, fellow refugees from a hated regime. Neither is from Ukraine but they understood my devastation like few other friends could. They understand my banana stories.

Do they share a part of their identity with me in a way others don’t? I would say yes, but we aren’t from the same place(s). Identity is such an odd thing, being from somewhere and identifying as just one thing has always felt strange to me. A family member of my ex-husbands thought it so odd that I was deeply affected by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine because he couldn’t understand that I could feel both American and Ukrainian. “What is your country?” he asked when I tried to explain why it made me feel so sad. I have more than one, I wanted to tell him but realised he wouldn’t really understand that. His identity is tied to one place and one people, he is Swedish.

Our identities are tied up in our religions, our jobs, our countries in a way where there is a THEM and an US. I wonder if it isn’t better to be able to identify with more than one thing, with more than one culture, with more than one role, more than one people? I look at photos of my family spanning the years from Ukraine to the US, for me, onward to the UK and then Sweden and all of them are now part of where I’m from in some way.