Blaxplotation, From The Heart of Bogota

Tarantula Authors And Art collaborates with LA Art Stockholm to bring our featured artist of May, Edgar Jiménez

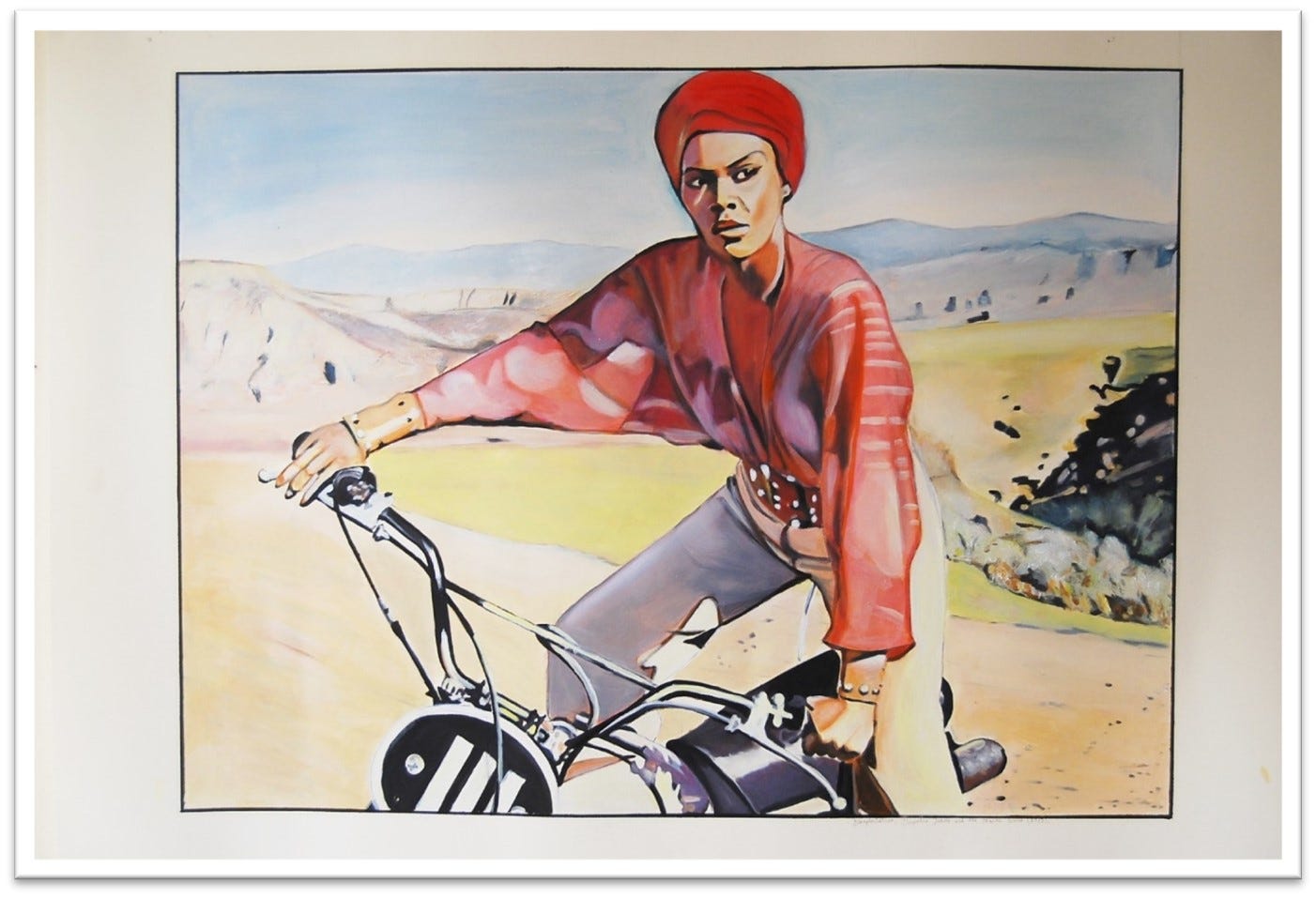

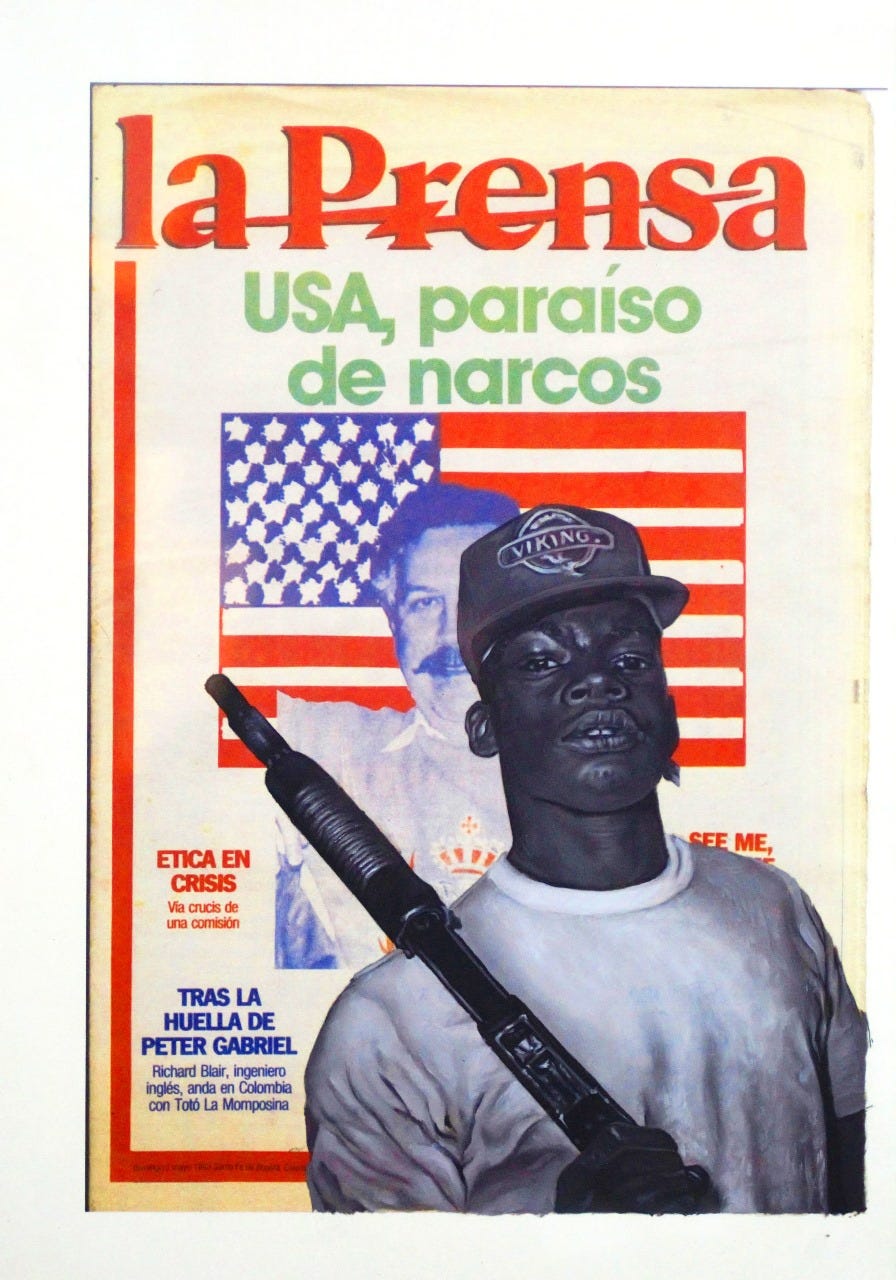

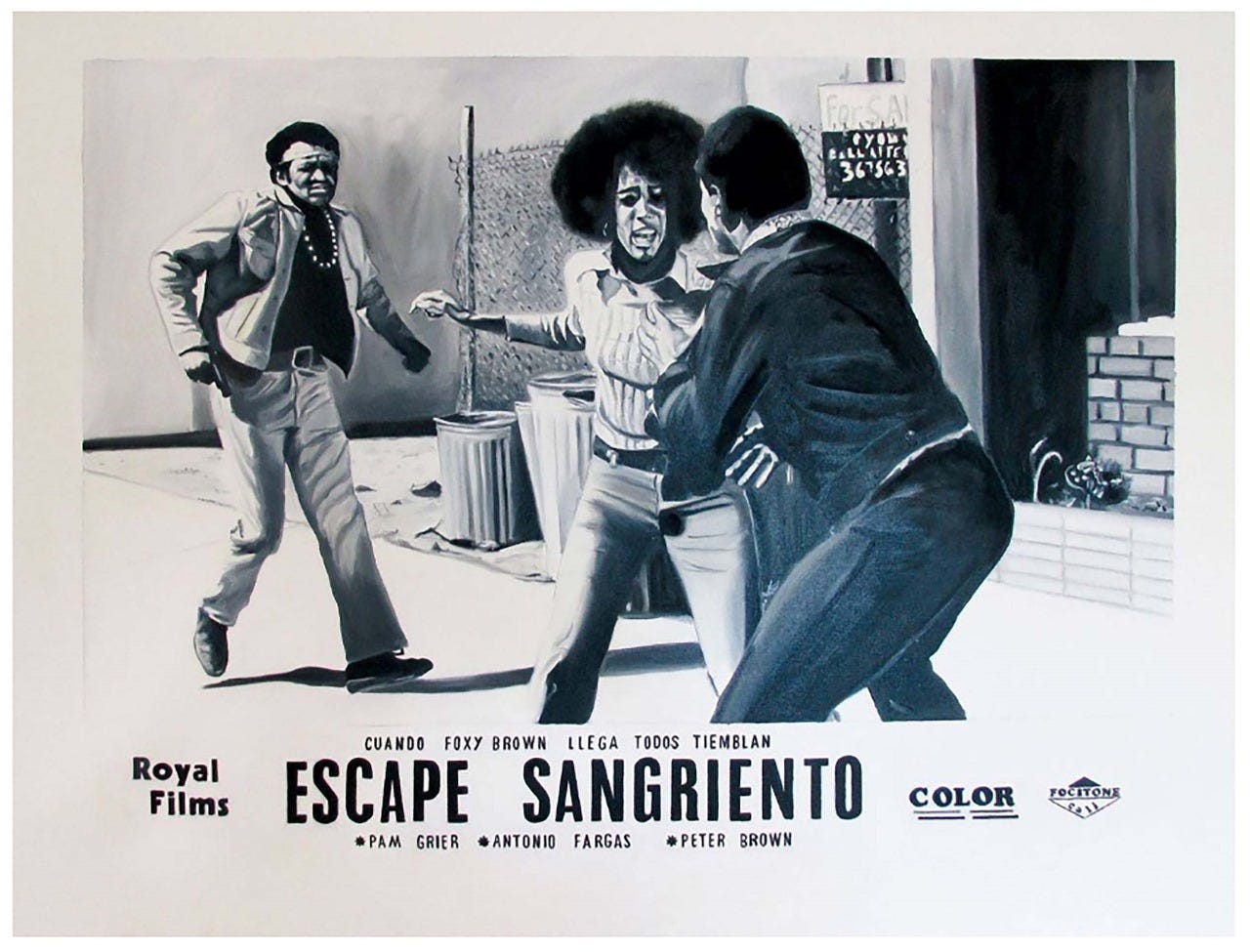

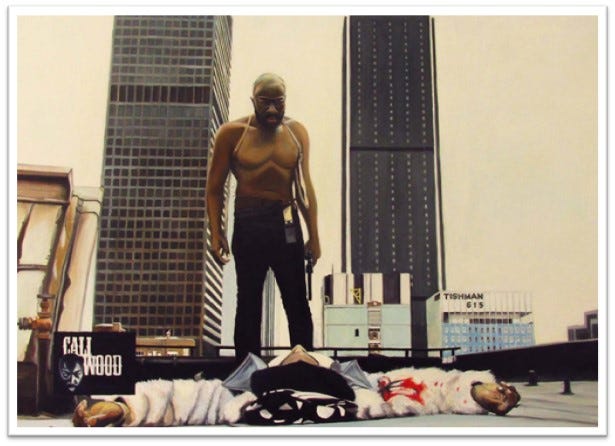

Colombian artist Edgar Jiménez takes B-side film posters to the next level. For over ten years, he has made paintings about racial segregation, employing an interplay between light and shadow to elevate the pieces to the point where the eyes get fooled and wonder, "Are these real?"

Moving from engineering into the arts and combining his love of cinema into his painting method, he touches on themes such as blaxploitation, punk, trash drawings, and more throughout his work. Jimenez has a lot to share with the world, and here is a look into his backstory.

Lorena Parada (of LA ART): Let’s start with who is Edgar Andrés Jiménez?

Edgar Andrés Jiménez: I am llanero from my mom’s side and Caleño from my dad’s side. We call people llanero who were born in the Orinoquia region of Colombia. My grandfather on my dad’s side was an empirical mechanic; I know that he repaired John Deere tractors between Bogota and Villavicencio in the 1950s. My grandfather on my mom’s side shared cambuche (a colloquial word for tent) with “Tirofijo” during the years of violence in Colombia (1948), even though all he did was try to escape from violence.

I was born in 1980. An incredible number in regard to historical events. I like that I was born this year. Now that I think about it from a distance, I was born in the year I wanted to be born, one year after my parents got married. Classic rock had already established its legacy. When Kubrick, Truffaut, and Fellini had already left incredible cinematic pieces for humanity...

I was the first child of the marriage. A sister arrived five years later. My childhood was amazing. I was interested in the sensible world since I was a child and I enjoyed reading, writing, painting, and finding fossils. I did all this naturally, but it never crossed my mind to become a professional in these fields. That is how I finished high school, and I went on to gain admission to electronic engineering. I studied for three years, which was not too difficult; I had incredible experiences, and most importantly I met people from other regions of the country which made me feel fulfilled. I had something of an anthropologist and something of a sociologist in me.

It sounds like you had good reason to pursue an engineering degree, how did arts cross your path?

I remember that when I started losing my interest in the degree, I became a frequent visitor of the library and the film club. I enjoyed spending lengthy hours on the campus of Valle University, an important public university in Cali and Colombia. I enjoyed hanging together with the alternative crowd—rock fans and sociologists. We talked about books and movies, and it evolved from a hobby into a question at the age of 22: What if I dedicate myself to this? What do I need to study in order to work full-time in this field? These are the questions I had. It could refer to literature, languages, or the arts. Arts? How do you study art? Where? How do you get into it? My curiosity was already sparked by art. Colorful cables, condensers, and electronic circuits had become a cold world for me.

I came home determined one day. I called my parents and told them it’s over; I am no longer studying for this degree and will look for something else. They continued to look at me without saying anything against it. “Let’s see what else is there that you find interesting,” is what they said instead. They were understanding after all. So, without further ado, I enrolled in the school of arts of the city; I was admitted, and that was the beginning of my full involvement.

Determined is the way to go. Your art practice, while diverse, is heavily focused on poster-style paintings; what subjects or circumstances inspired you to create them in particular?

Subjects and processes have always been linked to my current experience. It relates to my lifestyle, including my breakfast and lunch choices. Making art is a really immersive experience for me. That is why, if we go back to 2000–2010, while I was studying in Cali, you will find me discussing films all day. Films changed my existence. I was also very lucky since there were seven or eight film groups available Monday through Friday at the university. I had no way to escape! I went to the movies on Mondays at 6 p.m. with the elderly and AA. I went on Wednesdays with the Goths and those who went to see Zombie movies at Luto’, an artist from Cali and the creator of Videodromo, a movie club that specializes in B-movies. On Fridays, I would travel to Valle University to view essay movies (3-hour long) in a room with no audience.

That's how I spent the 2000s until landing a job at a video store. That was the laser disc's final kick. And I had a great time because people would come in asking for this or that film they had been instructed to watch, and I would give them a review, chat to them about the author, and they would leave intrigued and return two days later, incredibly thrilled with my recommendation. I became a movie critic. Of course, I brought a lot of VHS oldies with me from the store. I then created my own movie club, which is another long story from those days.

I loved documentaries. I liked the idea of making a story on the go as you gather material, characters, and testimonies. I believe that editing the videos brought me closer to painting.

I took as much as I could from Cali, my home city. I worked on a film shoot the year before moving to Bogota. I filmed a few documentaries and was a member of the collective Casamata together with Marcel Narvaes. I created free murals and a lot of great things for the city. And then I left!

You left for Bogotá. What has changed?

My Bogota stage is what I consider to be my professionalization period. Even though it sounds cliché, it was here that I discovered what I could and couldn't achieve, as well as the scene's limitations. Even if you are an outstanding artist, you cannot work on an empty stomach. But I'm not complaining. It didn't go badly. I began painting in full, to "produce artworks" as they put it, and as I became acquainted with the artistic environment, I understood that this could be an exciting city.

I had a lot of stuff in my bag from Cali. The most of them come from Cali's alternative scene: Rayita (the drawings about stray dogs), being a melomaniac, chit-chatting with people, and tropical goth. In the 1980s, readers of poets Edgar Allan Poe and Horacio Quiroga created the tropical gothic genre in Cali - a vampirism resulting from an excess of Rolling Stones, speed, and Nembutal. It is related to refusing to understand that childhood and adolescence are periods of life that must be left behind. That is when your brain goes crazy.

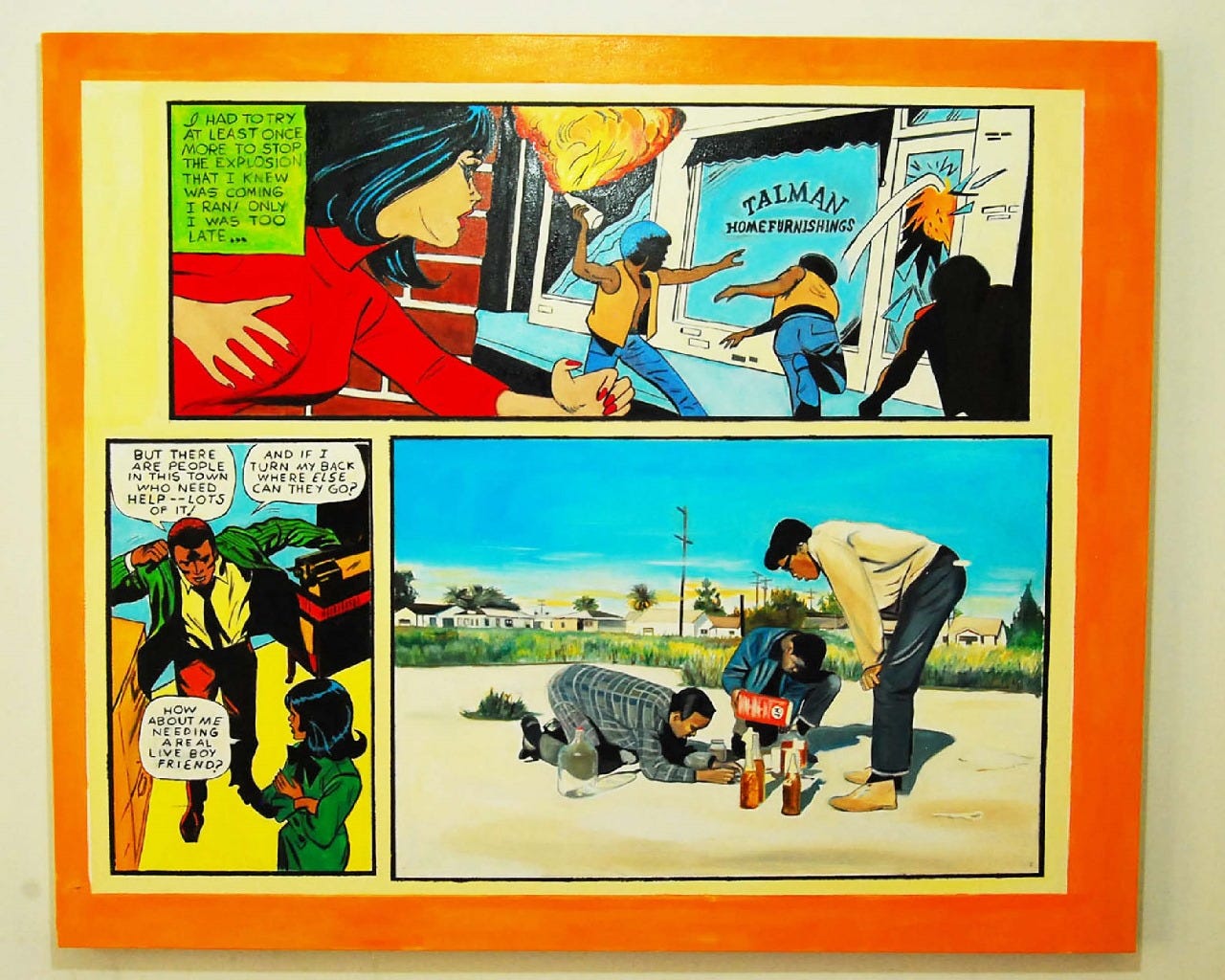

I got lucky in Bogota. I quickly connected with a group of incredible artists, such as Alex Rodriguez, Fernando Pareja, and Julio Acero, and I encountered Blaxploitation, which was a crucial theme in the creation of my work. At Alex's studio, I learned about the focus and devotion required to attain your goals. That nothing changes from one day to another. Also, motivation, because if you're going to paint from one side to the other on a two-meter-wide canvas, you have to be completely convinced of what you're doing. With all that going on, my processes have accelerated.

You said Blaxploitation was key in your work. Please tell us more.

I am an Afro-American descendant, and I have always understood that you cannot discuss racial issues indirectly. Or maybe I just wasn't interested in tackling it that way. Racial segregation has been a direct affront against the black people, and as a result, the subject will not accept mild color ink. That's how, one day while traveling through Bogota, I came upon old movie posters featuring Afro-American actors. It took me a few days to investigate the subject because there are very few sources on Afro-American history in Colombia, but I eventually found them.

My visual process with Blaxploitation developed naturally. Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Edward Hopper, and all North American Pop Art are represented in these works.

Unfortunately, I understood that Pop Art was a movement that reduced "Afro-American Art" to a subgenre reserved for minorities. They don't mention Jacob Lawrence or Kerry James Marshall at university; you have to look them up yourself.

Until the 1950s, blues and jazz were music by and for Afro-Americans; this is how they viewed Afro-American arts in the North American scene, particularly in modern times. In the 1970s, a group of activists and Afro-American artists began making Afro-American films without requesting permission and following in the footsteps of jazz musicians.

It's intriguing how I tackled the race theme in my artwork by including foreign references. But that's how it happened; that was the only open door for me.

It seems only natural that your series Riots, Gangs and Crack followed up Blaxploitation

I switched from Blaxploitation to Riots in 2016, which also has a heavy historical background that fascinates me much. Then, in 2018, I began working on the Gangs series, always thinking about how to approach the subject from a local perspective. And, as I already stated, Latin American schools and universities do not teach Afro-American history. Coloring history with white is an old practice that dates back to Argentina and Panama. So I needed to dig a lot. I encountered the texts of the writer Manuel Zapata Olivella, who brings out many facts about the history of Afro-American descendants in Latin America.

You have made murals as well.

While I was reading Olivella's texts, one caught my eye. It is "He visto la noche" (I have seen the night), in which Olivella travels around segregated North America in the 1950s and witnesses the battle of African-Americans against racial segregation. There is a visceral portrait of what it was like to be black in rural North America, particularly in the southern states, where people were hanged and lynched publicly. The home of the KKK. Olivella opened my eyes, but I remained inquisitive since I didn't know how to relate to this in my own context.

I was then living in the heart of Bogota, a beautiful area rich in history and architecture from several eras in Colombia. Bolivar Square, Salmona Towers, the National Museum, iconic theaters, old school booksellers, coffee shops, and historic structures rich of history. At the same time, Plazas de Mercado, emerald dealers, and individuals from all over the country flocked to Bogota to conduct business and rebuscársela (rumming for a living). The term rebusque (rummage) refers to looking in places where others have looked before.

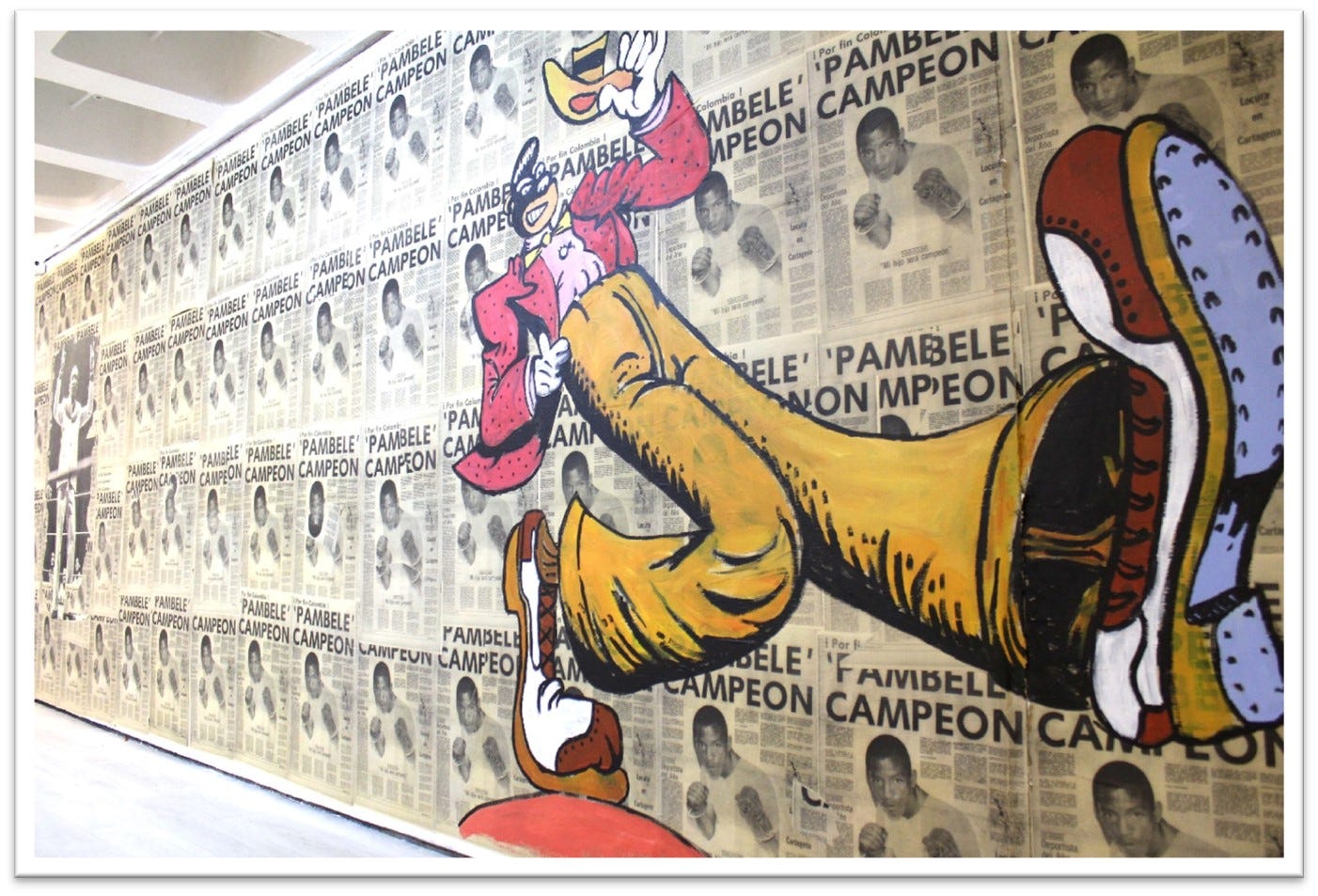

That is how, one Sunday morning, I was wandering through a typical gipsy flea market in Bogota (copper and bronze mingled with 80s porn) when I noticed a strange newspaper ad that caused me to turn back. It was an ancient but intact newspaper with the headline "At last Colombia, Pambelé Champion!" The first page title is dated October 29, 1972.

I took the paper home with me. It was the story of Antonio Cervantes "Kid" Pambelé, an Afro-American who had reached new heights by fighting in rings all over the world. His story began in San Basilio de Palenque, near Zapata Olivella: the first town freed from Colonial America, the town of Cimarrones (Cimarron was the name given to slaves who escaped when they declared a confrontational attitude toward their masters and found themselves usually near a Palenque). Cartagena authorities, acting as representatives of the monarch, enacted a variety of steps to punish fugitive slaves.

Pamblele’s history and its connection to the center of Bogota date back to the 80s and 90s. His life changed dramatically when he won the world championship in Colombia. He went from being a fruit seller in Cartagena to becoming a citizen of Panama. Pambelé became a national hero, appearing in all publications and media outlets. Money and celebrity went hand in hand. Pambelé became a frequent visitor to the government palace, befriending the vedettes and presidents. He drove a Mercedes-Benz, stayed at the best hotels, and dressed in the nicest suits. His life became a roller coaster. He was the world champion for seven years before everything came to an end. His money was over. Nobody could stand him or wanted to care after him; his use of psychotic substances had made him bipolar. He roamed around Bogota's center for a few more years, but he no longer went to the government palace; instead, he went to the drug corners that encircled Bolivar Square. His physical body enabled him to walk and go around the country. Everyone said they had just seen him and that he had passed by. That the officers apprehended him, that someone shattered a bottle on his head, that he was signing autographs at the plazas de mercado, and that he sold his world championship ring to pay for drugs. This is how the legend of Kid Pambelé began.

So, the primary objective of this artwork about Pambelé was to enable the city's history memory, to connect passersby with the intervention in the public space, which is continuously changing, much like the posters of the hero of the moment.

This artwork is called "El Campeón" (The Champion), and it consists of approximately one thousand posters that covered lanes and squares in the middle of Bogota, forming a trail that led to the Colombo American Cultural middle.

You belong to the group Proyecto Faenza, how’s this experience been?

I have been a member of the collective Proyecto Faenza since 2015, and we recently exhibited in Sweden. I feel that when you join a group, various ways of thinking are triggered, and processes or thoughts in the back of your mind are much enhanced. Being in a group makes a lot of sense in Colombia because you actually have to perform all roles to get your artwork across, to make people aware of it, to be judged, and commercialized. However, a collective is also significant since other members can have distinct views on the process of creating an artwork. Sharing space and seminars with other artists has always helped me learn more. That is how I learned about comics and art, visual approaches, and even project management, which is necessary when applying for grants and submissions.

What’s cooking?

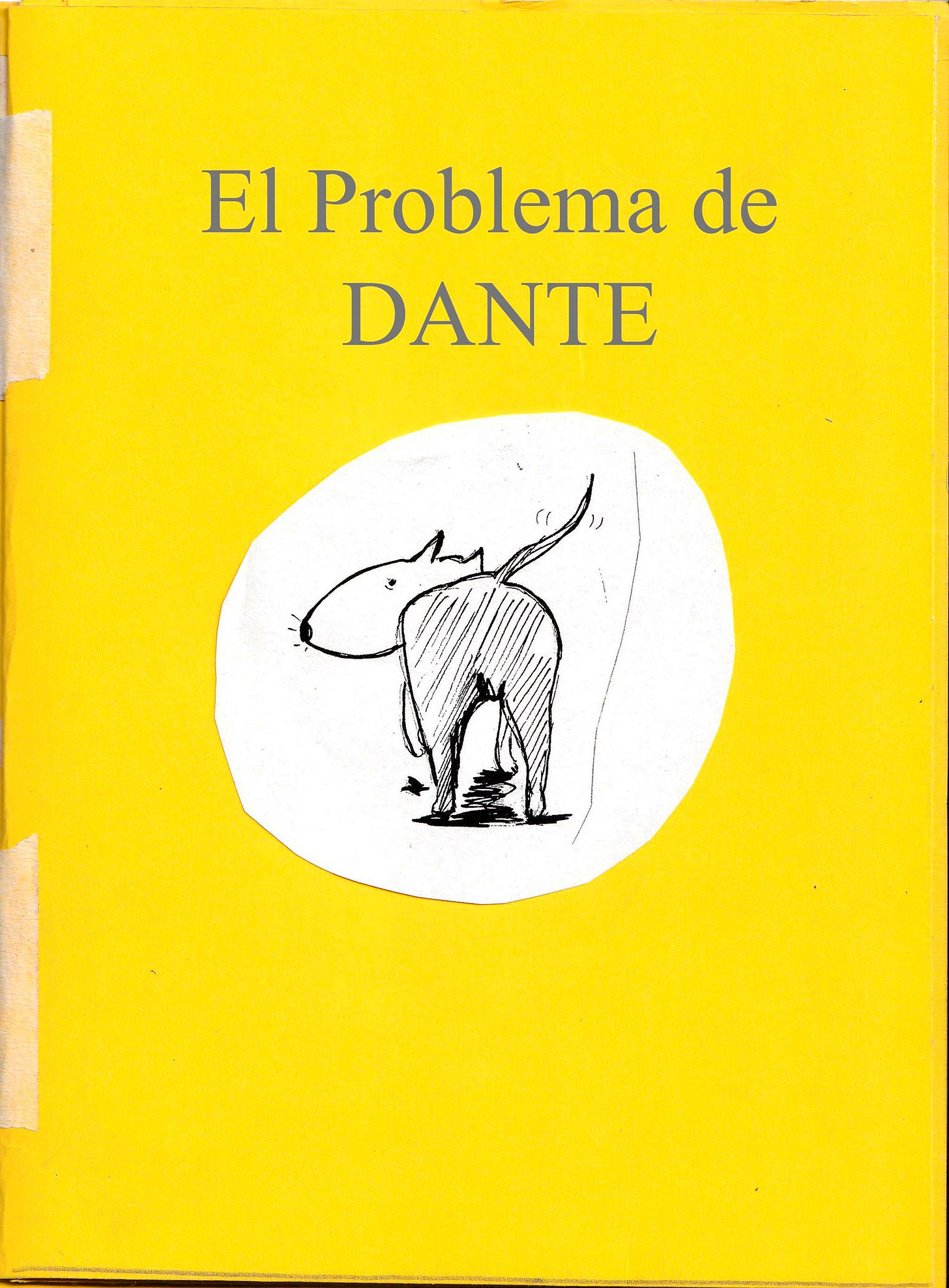

I'm looking for an editorial for "Rayita" and "El Problema de Dante" (Dante’s Issue). I wrote two illustrated books on rescued street dogs in Cali, Bogotá, and Medellín. That's all for now, and I continue painting and drawing as usual.

Thank you Edgar for this proufound conversation. To follow Edward’s work, please follow his Insta page!