Crimson Dreams

A conversation with curator Sona Stepanyan about Tarantula: Authors and Art's inspiration for January, Sergey Parajanov

Crimson red splashed across my screen like spilled blood. A woman’s face appeared beneath a red, pointy hat, echoing folklore from a country unknown to me. Her dark eyebrows and eyes were framed like a painting. I was watching a video by the Iranian band Kiosk; their song Yarom Bia belonged to my then-favorite film soundtrack, from A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night by Ana Lily Amirpour. I later learned that the surreal images—some of the most beautiful visual poetry I had ever seen—belonged to Armenian filmmaker and artist Sergey Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates.

Despite never having seen the film in its entirety, even now, when I close my eyes, its images flash behind my eyelids; they have become part of my interior design. As a non-Armenian, the footage does not carry the same historical meaning for me, but it serves as a reminder of the highest form of creativity and of the potential of imagination and dreams.

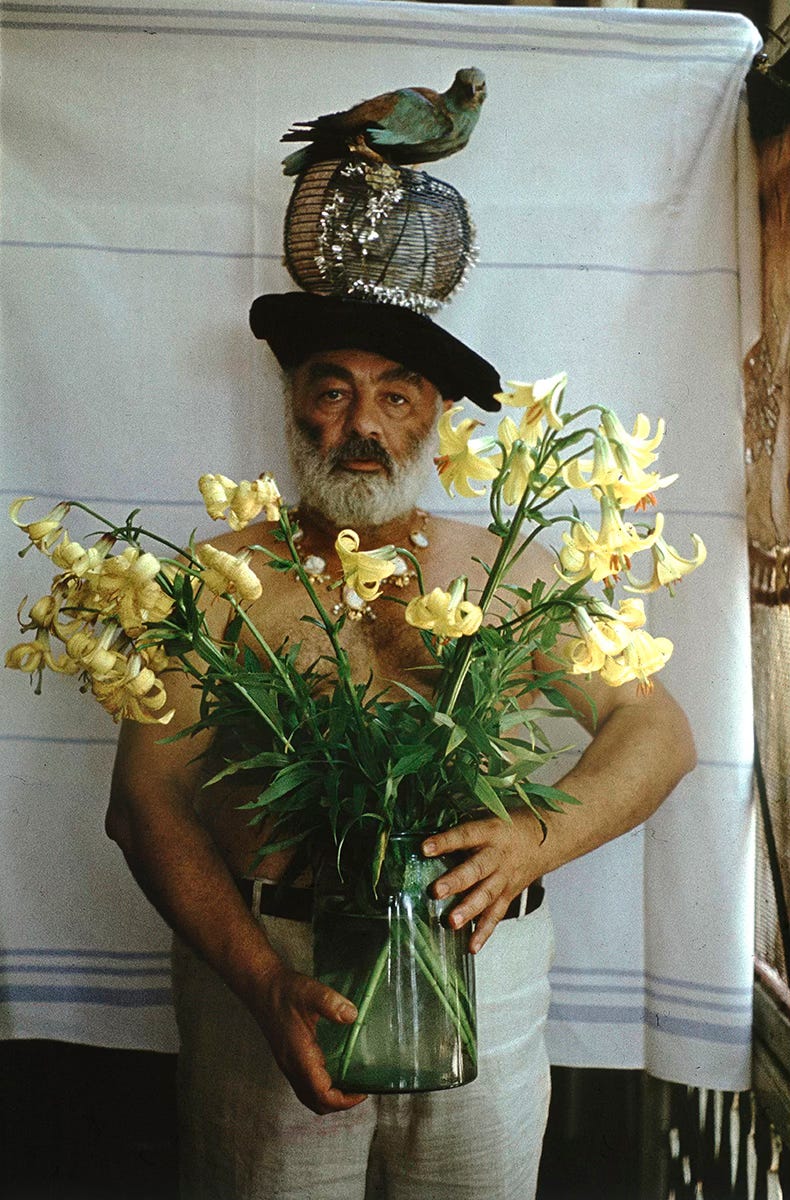

When my friend Malin mentioned a retrospective of Parajanov’s work at Södertälje Konsthall, I joined her on the train from Stockholm, unaware that I was about to fall in love with the artist-filmmaker. At the museum, housed in a beautiful old Swedish building, Armenian-born curator Sona Stepanyan—with her firsthand knowledge of the culture and remarkable storytelling skills— led us through Parajanov’s life and artistry. The exhibition included not only his films and photographs from his private life, but also censored footage, collages, and drawings from imprisonment.

As artists and filmmakers often feel the need to stay true to one form, it was lovely to see that Parajanov was unafraid to experiment. He created deliberately kitschy collages, gluing plastic bead necklaces and bracelets onto them. Stepanyan explained that under Soviet rule, these beads may not have held monetary value, but they symbolized small luxuries—and, above all, beauty - within the system’s grayness. When they broke, people would bring them to Parajanov so he could preserve their memory.

That same devotion to aesthetics, however fragile or defiant, extended far beyond these small gestures. It is hard to imagine that with such beauty, color, and symbolism, his films were the very reason he was imprisoned three times. His visual language influenced cinema across the world — even Lady Gaga drew inspiration from it for her video 911 — yet the regime did everything it could to erase his name.

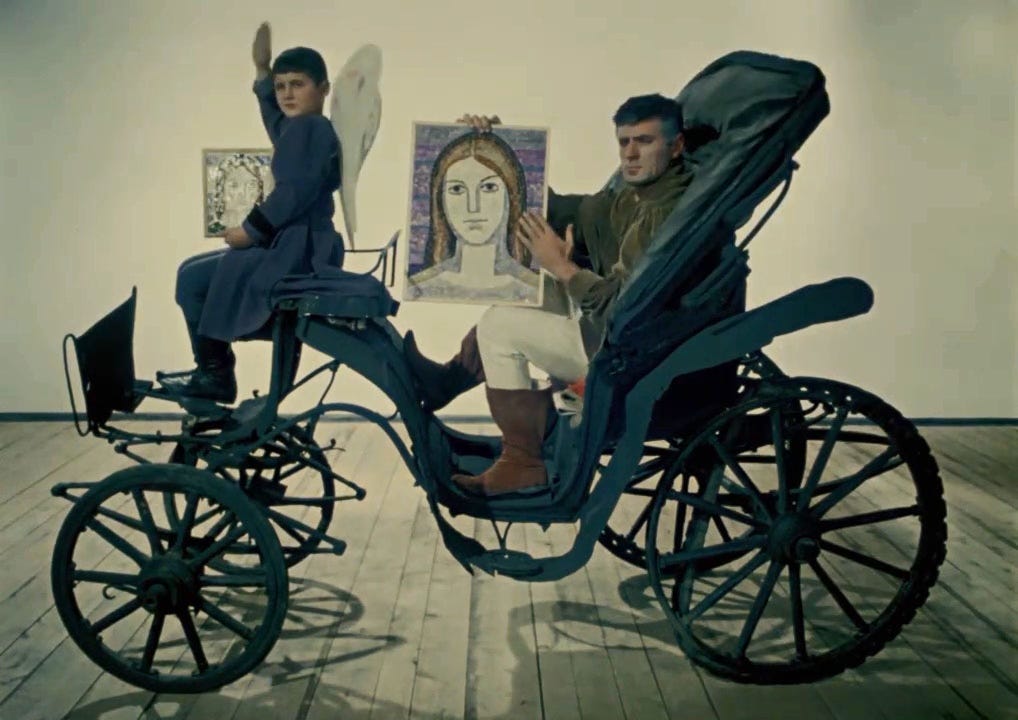

I came to the exhibition with images of The Color of Pomegranates, but I left most affected by The Kyiv Frescoes, commissioned by the Soviet government to commemorate WWII. Instead of worshipping soldiers, Parajanov presents them as civilians in the aftermath of war—changed, marked by trauma. How contemporary, I thought. He was a true visionary.

The traumatized soldiers appear in dreamlike sequences, and I hope that even in those darkest moments they knew that, even if everything was taken from them, they still had the right to dream. To dream, to imagine—this is where new worlds begin and old regimes start to crumble. From imagination, protests are born: from the insistence on making dreams real, and from the desire for the crimson color to finally represent love.

What do you see as your role as a curator, and what kinds of themes are you most drawn to exploring in your work?

I am primarily drawn to learning from and with artists — this is where I most strongly locate my role as a curator. I am led by artistic practices themselves. Depending on context and historical conditions, curators are often expected to assume more managerial or logistical functions or be mediators between art and the audiences. When that becomes necessary, I prefer to approach such responsibilities through the lenses of contexts, systems and institutions rather than purely through operations.

You are Armenian, like Sergey Parajanov, whose work you curated at the Södertälje Konsthall. Were you influenced by his work early on? If so, how?

Absolutely — in many different ways, and at many different moments of my life and age. The experience was never singular but layered: fear and fascination, crying and laughter, longing and rejection, admiration and shame. Parajanov does not produce one emotion, one memory, or one lesson; he produces a field of feeling that keeps changing as you change.

When you come from the same places and share the same languages — linguistic, bodily, visual, political — your perception becomes more precise. You begin to hear what is not said, to register silences, pauses, and other codes. Over time, this attentiveness becomes a way of living with the work, not just encountering it.

You shared at the viewing that many Armenian parents made their children watch The Color of Pomegranates. What did that film symbolize for them?

I will begin with my own family and people I have known. For children, the film is meditative and often not immediately engaging. Yet Parajanov himself enters Armenian life very early: his name is familiar from childhood, schools regularly bring children to his museum, and he becomes part of one’s first encounters with culture and history.

What I meant when speaking about Armenian parents is not a single fixed generation, but rather several overlapping ones—shaped since 1969, when The Color of Pomegranates was released—people who lived through very different conditions: the Soviet period, life in the diaspora, and later the years of independent Armenia. Across these shifting contexts, Parajanov seems to have occupied a singular place. He appears not only as a cultural figure but as a kind of reference point through which questions of identity, memory, and belonging are continuously reworked.

His importance for Armenian culture feels difficult to measure, and at the same time unmistakable. He carries and, in many ways, reshapes a contemporary cultural sensibility. His influence extends far beyond Armenia, into the broader history of cinema and visual language. At the same time, from the position of a curator working with visual art, it feels important to acknowledge how much of his work — especially his visual practice — still remains insufficiently studied, insufficiently written about, and insufficiently present in major European museum collections. In that sense, Parajanov continues to exist in a space between recognition and invisibility, between what is known and what is still waiting to be understood.

You curated the Parajanov exhibition currently on view at Södertälje Konsthall and titled it The Right to Dream. What is our right to dream?

It is the only right that cannot be taken from us when all other rights have already been taken away. The title itself is drawn from Parajanov’s own words — from his diaries, letters, and interviews — especially when he speaks about his experience of imprisonment.

You described it as something of a miracle that a small institution like Södertälje Konsthall was able to present Parajanov’s work, given that he is usually shown in major museums worldwide. such as Moderna Museet. How did this “miracle” come about?

There are several reasons why this project came together in the way it did. Whether we want it or not, we are living in a time shaped by war — not only the ongoing invasion of Ukraine, but also the two brutal wars Armenia has experienced in the past five years. Exhibiting art has never been separated from questions of logistics, borders, routes, resources, and escalating costs. In the present moment, this interdependence becomes especially visible. Institutions are increasingly forced to work within tightened constraints, relying on what is locally available, negotiating rising costs, shrinking routes, and fragile infrastructures.

Against this backdrop, it truly felt like a miracle that we were able to realize a solo exhibition composed entirely of museum loans. It required an extraordinary degree of trust and courage — from the Parajanov Museum in Yerevan, from the small but deeply committed team at Södertälje Konsthall, and from all partners involved. Together we produced a project with the scope and complexity of a major institutional exhibition, including multilingual materials, publications, and an extensive public program.

Several broader conditions also shaped the moment. The exhibition almost coincides with the centenary of Parajanov’s birth, which has been widely commemorated in Armenia and internationally. At the same time, Södertälje itself is a city with a large and multi-layered Armenian community, including members of older diasporas from Lebanon, Syria, Iran, Iraq, and even Poland. The city plays an important cultural role, supported in part by the active work of the Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Mary, where educational and cultural programs are continuously developed.

Finally, there is the contemporary relevance of Parajanov himself. His life — marked by exile, censorship, migration, and the continuous reconstruction of both artistic and human identity — resonates strongly with current cultural debates in Sweden around artistic freedom and the limits of state intervention in creative practice. For all these reasons, the project emerged not simply as an exhibition, but as a meeting point of historical memory, present urgency, and shared cultural responsibility.

In what ways did Parajanov’s refusal of borders - sexual, national, and artistic - become both the cause of his persecution and the source of his artistic freedom?

Parajanov’s life and work were built on radical openness. His refusal to submit to rigid identities — whether sexual, national, or aesthetic — directly challenged the ideological machinery of the Soviet state. This defiance made him dangerous in the eyes of power, and therefore subject to persecution. Yet the very same refusal liberated his imagination. By rejecting imposed boundaries, he constructed an artistic universe that remains unmatched in its freedom, hybridity, and emotional intensity.

Parajanov began his career making films in a more conventional cinematic language. At what point did he decide to radically change that language and move toward a more Dadaist or surrealist approach?

The turning point came in the mid-1960s, particularly with Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. From that moment onward, he increasingly abandoned narrative realism in favor of a language built from ritual, image, rhythm, and symbolic composition — a cinematic grammar closer to collage, poetry, and dream than to classical storytelling.

There was a striking contradiction in his relationship with the Soviet authorities: he was censored and imprisoned, yet repeatedly invited back and commissioned to make grand, state-sponsored films celebrating events such as World War II. Brezhnev, who sent him to a labor camp for five years, reportedly asked upon signing his release papers, “Who is Parajanov?” How do we understand the fact that he continued to be hired despite being labeled an ‘enemy of the state?’

This contradiction reflects the deep ambivalence of Soviet cultural politics. Parajanov’s genius was undeniable, and the state both feared and desired it. While he was punished for his independence, his talent was also exploited when it suited ideological spectacle. The system could not fully erase him, nor could it truly tolerate him.

Kyiv Frescoes was commissioned to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the victory in World War II in 1965. Instead of glorifying soldiers, Parajanov chose to depict the aftermath of war—nightmares, trauma, and PTSD. He must have known this would lead to another ban. How did he justify making the film, knowing that his message might never reach the public? When and where was the film first shown?

The ideological expectations surrounding this commemoration were extremely rigid: the film was meant to glorify military heroism and the victorious soldier. Parajanov did something radically different. He chose to place at the center of the film not the soldier, but the person — a civilian figure moving through Kyiv on Victory Day. His original concept consisted of a series of “cine-frescoes”: poetic, fragmentary tableaux unfolding across the city. Among the central figures were an unnamed Man, also a war Widow, a Longshoreman, and other everyday characters. The city, its artworks, its people, and their private memories become the true protagonists.

Rather than celebrating war, Parajanov was contemplating its aftermath: memory, loss, disorientation, survival. He was already fully aware that such an approach would be unacceptable to the authorities, yet he continued working. For him, the ethical necessity of making the work clearly outweighed the likelihood of it ever reaching the public.

The project was soon shut down by the studio, the negatives destroyed, and only about fifteen minutes of screen tests and fragments survived. These fragments were later preserved and circulated internationally as an independent short work, offering a rare glimpse into the visual language Parajanov was developing just before The Color of Pomegranates. In this sense, Kyiv Frescoes exists today not as a completed film, but as a powerful trace of what his cinema was already becoming — and of the cost at which it was made.

Though not religious, Parajanov repeatedly used religious imagery. Was it a means of connection—or a provocation against the Soviet state?

I think it was a way of connecting the vast continuity of art histories with the fleeting span of human life.

How did Parajanov discover collage, and why did it become such an important part of his artistic practice?

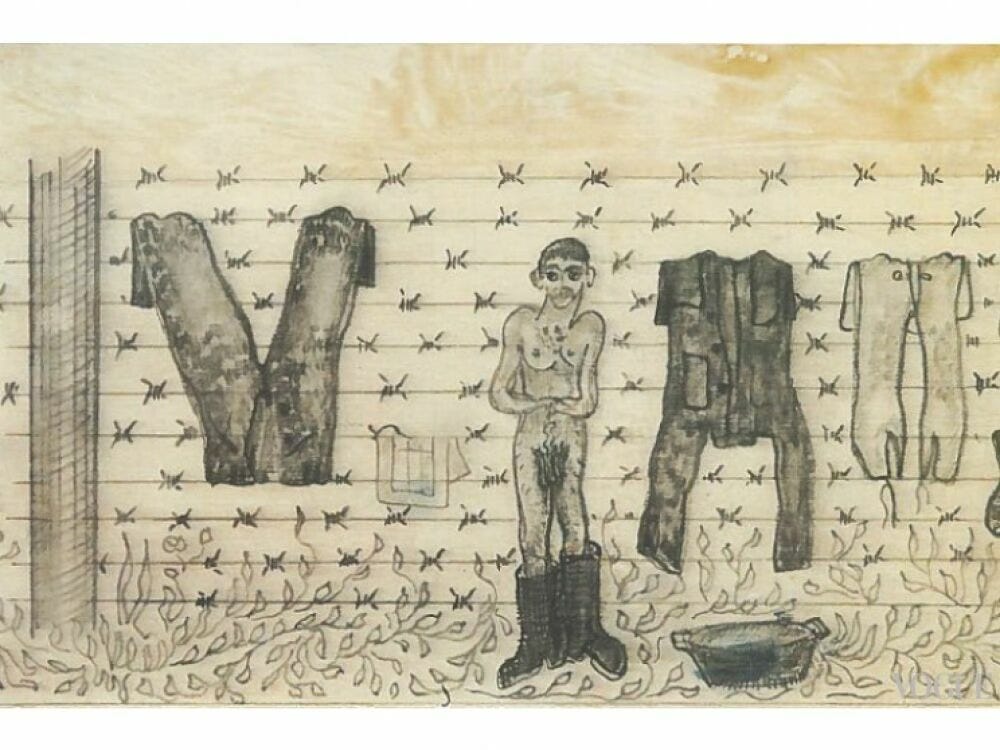

The works Parajanov created during imprisonment and after his release — when he was banned from filmmaking and expelled from the Union of Cinematographers — occupy a special place in his practice. Deprived of cinema for fifteen long years, he turned to what he called “compressed films”: collages. These were not just substitutes for cinema but experiments in building narrative, rhythm, and symbolism through material, gesture, and image.

During his time in prison, Parajanov worked with whatever materials were at hand: scraps of burlap, candy wrappers, matchboxes, playing cards, dried flowers collected during walks, and foil from milk bottles. He fashioned dolls, still lifes, and small reliefs, developing an intensely personal, almost diaristic language. These objects became both survival and resistance — a way to persist in creativity under conditions of extreme constraint. After his release, he returned to collage and painting, revisiting cultural icons such as the Mona Lisa, and transforming everyday materials into carefully composed, intimate visual narratives.

In the exhibition, we do not separate cinema and visual art, because in Parajanov’s case the methods and aesthetics are the same. At the core of both is collage, tableau vivant, and constant references to art history — whether a Renaissance painting, a medieval Armenian manuscript, or a Persian miniature. In that sense, one could also say that he began working with collage long before the physical artworks themselves came to life; the logic, rhythm, and composition of his later collages were already present in his cinematic imagination.

Can you tell us the story behind Parajanov’s Mona Lisa?

It was also in the labor camp that the story of the Mona Lisa first took hold in his imagination. Parajanov reportedly saw a fellow inmate with a small tattoo of the Mona Lisa on his shoulder. Depending on the inmate’s movements and posture, the figure seemed either to smile at him or to weep for him. The image — iconic, enigmatic, and intensely intimate in this unexpected context — left a profound impression. It became a touchstone for his later reinterpretations of Western masterpieces, where fine art is transformed into something personal, poetic, and often ironic. His Mona Lisa works are playful yet deeply reflective, bridging private experience with the universal language of art.

What’s the symbolism behind Parajanov’s crimson and other colors?

For Parajanov, color is never merely decorative; it is a form of language, a way to encode emotion, history, and cultural memory. Crimson embodies life, sacrifice, love, blood, and remembrance — a chromatic condensation of existence itself. Gold evokes the sacred, echoing Byzantine icons, medieval Armenian manuscripts, and Persian miniatures; it carries both spiritual and historical resonance. Blue often signals distance, melancholy, or transcendence, while green suggests renewal, fertility, and continuity.

These choices are deeply informed by the convergence of Eastern and Western visual traditions. A single hue can simultaneously reference Renaissance chiaroscuro, Armenian ecclesiastical illumination, and Persian miniature painting. In this way, color becomes a bridge between codes — a dialogue between different cultural sensibilities, reminding us that images carry meanings far beyond the immediate or literal. For Parajanov, each palette is a meditation on human experience, history, and the shared visual language that transcends borders.

Parajanov lived openly and without borders in a world defined by strict limitations—loving across genders, embracing all nationalities, and responding to hostility with love. How would you describe his way of being in the world, and what can we learn from it today?

Parajanov’s art, shaped by countless cultures and worlds, continues to resonate across deeply diverse and sometimes polarized communities. What matters to me is that the exhibition can become a space where these communities can coexist — perhaps not always in active dialogue, but simply together, silently, in the presence of art. That, in itself, is already a form of learning.

Beautifully said. Imagination feels like the one freedom that truly endures, often becoming, as you wrote, a form of resistance in itself. Also, constraints, as those found in imprisonment, can quietly push us toward new and unexpected creative territories. Thank you so much for sharing your experience.

That point about dreaming being the only right that can't be seized when everyhting else is taken hits hard. I find myself thinking about how Parajanov's collages from prison scraps weren't just making do, but actually a more concentrated form of resistance than his films could ever be. When I was visiting refugee camps few years ago, people kept their creativity alive in similar ways. Maybe thats the real power here, not the grand artworks but the stubborn refusal to stop imagining.