It’s not often that we get a chance to get up close and personal with our featured artists. So, when we realized that Nina Buesing, Tarantula’s featured artist of July, has known our featured artist of November Andrea Chung for almost 15 years, we invited her to step into the role of the interviewer. After running into each other in the art world, they became friends when both became mothers a few years later, bonding over the challenges & comedy of parenthood.

“Andrea is a person as profound and caring as her art. Upon seeing Andrea's work, I knew she was the real deal. Andrea has the gift to transcend language and time through her work. While speaking with and to specificities, her reach is universal,” Nina Buesing shared with us.

What follows is an excerpt of the conversation between Nina Buesing and Andrea Chung.

NINA BUESING: Thank you for taking the time to answer these questions. I know this is a busy year for you! In a conversation with Photographic Arts Council LA's director Bayley Mizelle, you said that you came from painting but stopped painting. You talked about being “force-fed” Eurocentric art history and how that turned you off painting. Can you speak about that?

ANDREA CHUNG: I realized that I'm just not a painter. I love the physical act of painting, and I miss it at times, but I'm not a painter. I don't have a love for it the way some of my friends who are painters do. Like Firelei Baez, for example, she loves painting! First, she can draw her ass off, but she really is masterful in her painting, and she has a recall for painters and their techniques. I just never had that kind of training as an undergrad. I've always been more interested in conceptual work. But I didn't know that until I was in school and learned about conceptual work. So, I think that's why I work in various formats. I like painting, it is a very relaxing, physically therapeutic thing to do, but I just don't love it as other people do! You know what, it's not just that I'm force-fed Western art history, it is also that I don't want to have to think about that history when I'm painting. Like, why can't I just paint for painting?! I love painting, but I just want to avoid having to consider what some old Renaissance racist was thinking about when they were painting! I just want to paint because I love it.

And I think when you're an artist of color, you don't really get the chance to just enjoy it in that way. You always have to contend with the history of it – and that may not even just be for artists of color; that might be for like anybody who's a painter, a contemporary painter. I don't want to deal with that. And I think that the kind of sculpture that I do is more ready-made. And that it’s a little younger in terms of the format. So, I think that anything goes (in that format) and that that's more my speed. You can sort of play with different things, and you don't have to contend with the history.

Your choice of materials was (originally) influenced by what was available to you.

Yeah, I was broke during grad school. We had just gotten married. We didn't have any money, and my husband hadn't quite found a job when I was at MICA (Maryland Institute College of Art). So, it was more of “what are the cheapest materials that I have around me?” I had black paint, and I had white paint, and that was it—and butcher paper because I couldn't afford anything different. I think starting from nothing and not having many materials allows you to build a strong foundation and (shows you) what you're capable of doing with minimal materials. I took that painting background and then tried to find a material that was more suitable for my historical interests, and that's how I started painting with sugar and then; from there, that led to doing sculpture with sugar.

When did Sugar enter as a material into your practice?

2007

You did some residencies abroad. Did that experience bring sugar into your practice, or was it a more cognitive process? Did you consider sugar an analogy for all these things you were contemplating?

No, it started when I was in grad school. I had never had a studio, and I never had the resources I now had at MICAH. That was a new experience for me. Being in the setting of having other artists around was very different from my undergrad experience as well. I was doing many drawings and paintings about my family and really thinking of my family's history. My grandmother died while having her second leg amputated. She had that surgery because she had gangrene from diabetes. When I was a kid, my dad had to go to diabetic education classes because his blood sugar was high, even though he was really thin. Sugar has a huge role in my family. A lot of my family members have diabetes, and it's very common in the Caribbean because a lot of the food there is very starch heavy. You can attribute that to colonialism because of the foods that were brought there and that people ate to survive. They're starchy, like breadfruit, for example, which is one of my favorite things to eat there, but it's full of starch! Starch kept people full and energized with the ability to work, so it wasn't something that I didn't just like to happen upon, but rather it is a part of my family; it's part of my DNA.

I love the impermanence of your sugar sculptures. I love that it is not for prosperity. I always chuckle a little when I think about collectors buying, not knowing if it is stable.

Yeah, I like the ephemerality of it. You know it is somewhat twofold, like in some ways it's like f-you art world; I wish you would try to commodify this! (Laughs). But at the same time, these materials that I use have their lifespan, and I like that they have their history. I'm investigating their history, and then the work itself has its history; the work will constantly change over time. As a collector, you have to be willing to be invested in the work and committed to knowing that in this work, a sugar piece will eventually fall off and that you accept that. That's part of the work. You are a witness. I'm thinking of a few pieces I did, particularly Cyanotypes. These works were submerged in sugar and then crystallized. This work will change over time. But if you're really invested and truly believe in the work, you're willing to deal with that. The people who buy those pieces to me are my favorite collectors because they are invested in seeing how this work is going to change over the course of time. You know, you either can live with it or you can't. It is nice to see those pieces sold.

My response to your work initially was aesthetic. I liked what I saw, which drew me in, and then I discovered another aspect of the work. To me, the impermanence of your work ties it to the traditions of passing on stories. The idea of not having any real control, so you are doing what you can to transmit your story -

AC: That's an interesting way of looking at it. That is the very first time I've ever had anyone say that; that's an interesting perspective I hadn't considered!

NB: Your subject, and your themes, connect to the idea of folklore. Folklore in the traditional sense of passing on stories. Especially in the context of colonialism. Enslaved people’s options were so reduced in passing on stories.

AC: That is a really perceptive way of looking at it. I have never really considered that. That makes me feel really good that you could put that together and see that in the work is such a huge compliment.

That's what I took from it.

That is a unique read that I have never had anyone say, and that’s very meaningful. I hadn't considered my work in that way, and that's special because, like you said, I do talk about a lot of traditions that are oral and passed down, but I never considered the ephemerality of the work in that way, which is a really beautiful way of thinking of it. I appreciate that.

I think I am not the only one that responds to the aesthetics of your work. Many people will viscerally respond to it because it's visually beautiful. Everyone loves your collages with the beads for example. They are exquisite visually. But then there's this whole other layer to work! This is a great way to communicate: You engage the viewer, and then they are open to sit with the work.

I guess seduction has been part of the work that I never really thought about. It was never intentional, but I think that there is something to the beauty of something, like sucking you in, and then you realize how grotesque it is. I kind of like playing with dualities in that way because you understand the horror of what you're looking at. Even if it visually looks beautiful, you start to really see the messed up nature of the thing, and to me, that's interesting.

I was telling someone today that making jokes is my defense mechanism, and I think it's because there are things that are very painful, and the only way you can get through them is to laugh and make jokes. I think I approach that aesthetically by making something aesthetically pleasing. I won't say the work is beautiful because that's never what I'm going for, but I think it's aesthetically attractive, but when you really think about the conceptual aspect of what I'm making that there is something like horrifying or f–ked up about it. I like that because I think it makes people really think about what it is I'm asking you to consider. I feel that we are in a time of instant gratification, looking at things really fast. I hope that people will spend time with the work.

Absolutely! Your lionfish are like that too.

Lionfish are stunning to see in person, but my visceral response to them is the opposite. We saw one at the beach, and I freaked the f__k out. I was like, oh my God, okay, just like go away, and I inadvertently was pushing closer to it, but I knew they were poisonous, so my initial response was to run and get away.

I have one of your lionfish, a small work, in my house and somebody said how beautiful it is. Then I told them how the lionfish is an invasive species and an analogy to colonialism and slavery, and the person’s whole mood changed.

That's hilarious! I just ruined somebody's life.

I like that kind of response because it does stay with the viewer. I bet that if they go to an aquarium and see a lionfish, they'll probably never look at it the same way again. They'll think about that conversation you had with them, and that's kind of the goal - to stay on your mind, not to just you look at a piece and like it and then just walk away because then I feel like I didn't do my job.

Definitely. We have these pieces of information in our minds, and we often don't access them. Your work puts little seeds in people’s minds that grow and allow people to put two and two together.

I try to. I'm not good at asking leading questions, which is why I'm a terrible interviewer, but I try to do that in the work. I don't want there to be a “yes” or “no” answer to anything that I make. I want it to be a leading question where you have to think about your response to the work. I'm not effective at it verbally, as I am a shitty writer, but I will post those questions visually.

You talked a little bit about how painting is just fun. In general, your topics are so heavy, so I wondered if your work brings you joy.

I would say yes. I try to make it fun. If I don't, I'm not going to do it because I'm lazy like that, and I have to enjoy it somehow. I think that's why I hop around from material to material. Because every time, I try to find something new that I want to learn. I really did like weaving. I thought that it was a lot of fun to work with the baskets, and I thought I could do this. I could weave my own furniture.

But there's something about the repetitive nature of some of the things that I tackle, the tediousness of it. I'll complain about it as I'm doing it, but at the same time, there's something meditative about it. I don't know how to meditate. So, I think that's really good for me to do. Now, I'm beading, and beading is hard. It is probably the hardest thing that I've ever tried to learn how to do because it's easy to mess up the knot. You have to think about tension and certain patterns that you must master. I'm just not good at sewing, so beading is quite challenging. But again, it's this repetitive nature that's therapeutic; I can just sit with the TV on and just sit there and bead and bead and bead. And I really like that every time I take up a new material, I think about what could be done with it.

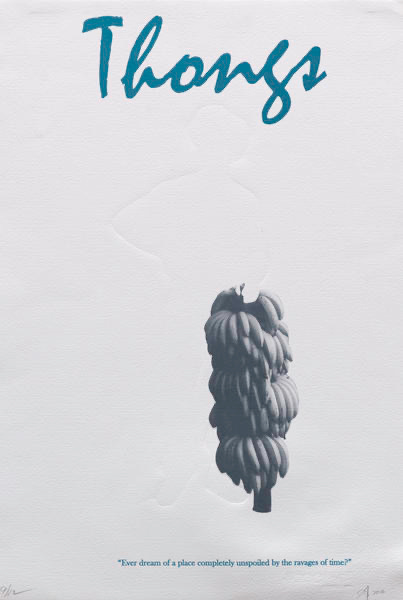

“Ever dream of a place completely unspoiled by the ravages of time?”

How has travel influenced your work?

Traveling to Mauritius on my Fulbright was impactful, and I think that made me think globally about how former colonies, particularly island nations, have many similarities. I've started meeting different people from other islands in Oceania, and the similarities are kind of unnerving because some of them are not great things for us to have in common. Still, there's also a sense of pride that, I think, is really interesting. Certain Islands look to each other for strength, which is cool.

The history of Jamaica has impacted Mauritius in particular. I thought that it was really interesting how Jamaica looks to Mauritius as an inspiration. Economically, Mauritius looks to Singapore because they're a cyber Island, and they're trying to define themselves in the same way, so it's really it's interesting how different colonized places are looking to each other as different examples of what are the possibilities of becoming less dependent on these former so-called mother countries. I keep thinking if we could just all bond together and just take over the world, it would be awesome.

Like England's an island. What if we just went over there and took over the whole island?

If travel was simple right now, and you could just go somewhere to take a break, where would you want to go or what do you want to see?

I like water; water is restorative to me, so it would have to be someplace by the beach. Mauritius was a great place to be; it's just far enough from the rest of the world.

There's a lot of beauty there, and it's the safest place. I've never lived with people that are so incredibly friendly. Any place with clean-looking water is restorative for me because sometimes I just need to sit in it and recharge my batteries.

To find out more about Andrea Chung’s work, visit andreachungart.com and andreachungstudio on Instagram.