Entwined in Time: Viola Sparre's Portrait of Family

A conversation with Tarantula: Authors And Art's Inspiration for November Viola Sparre

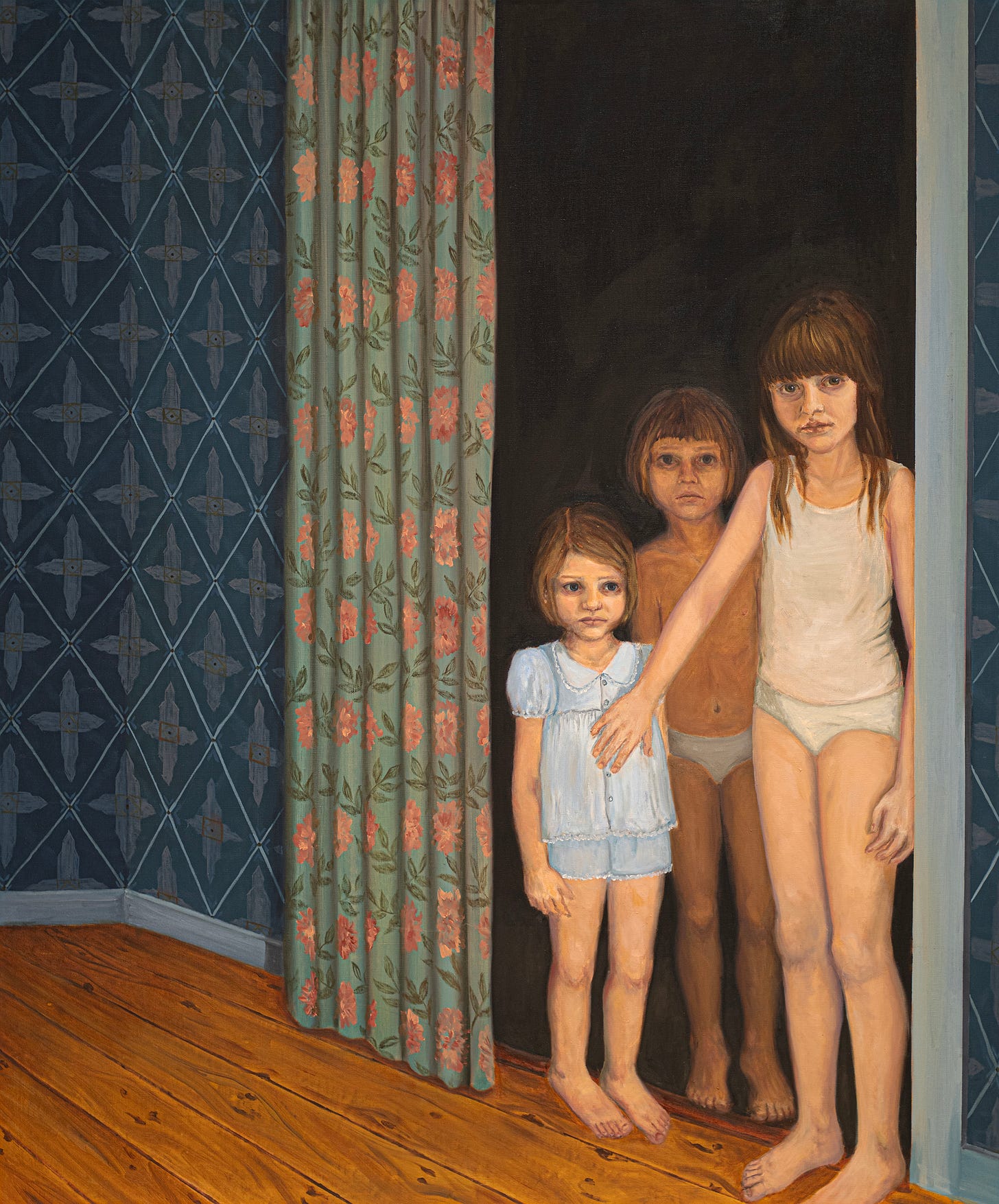

Three generations of girls share a single frame in one of Viola Sparre’s captivating large-scale paintings. They appear to be just a few years apart, but after a closer look and a conversation with the artist, one realizes the complexity of her vision. These girls represent different stages within a family line—mother, daughter, grandmother—all brought together in a surreal yet intimate “time warp” that bridges generational divides. By positioning them as contemporaries, Sparre invites her audience to reflect on the deeply rooted connections that define family bonds, hoping that this imaginative merging of ages might foster a deeper understanding between generations.

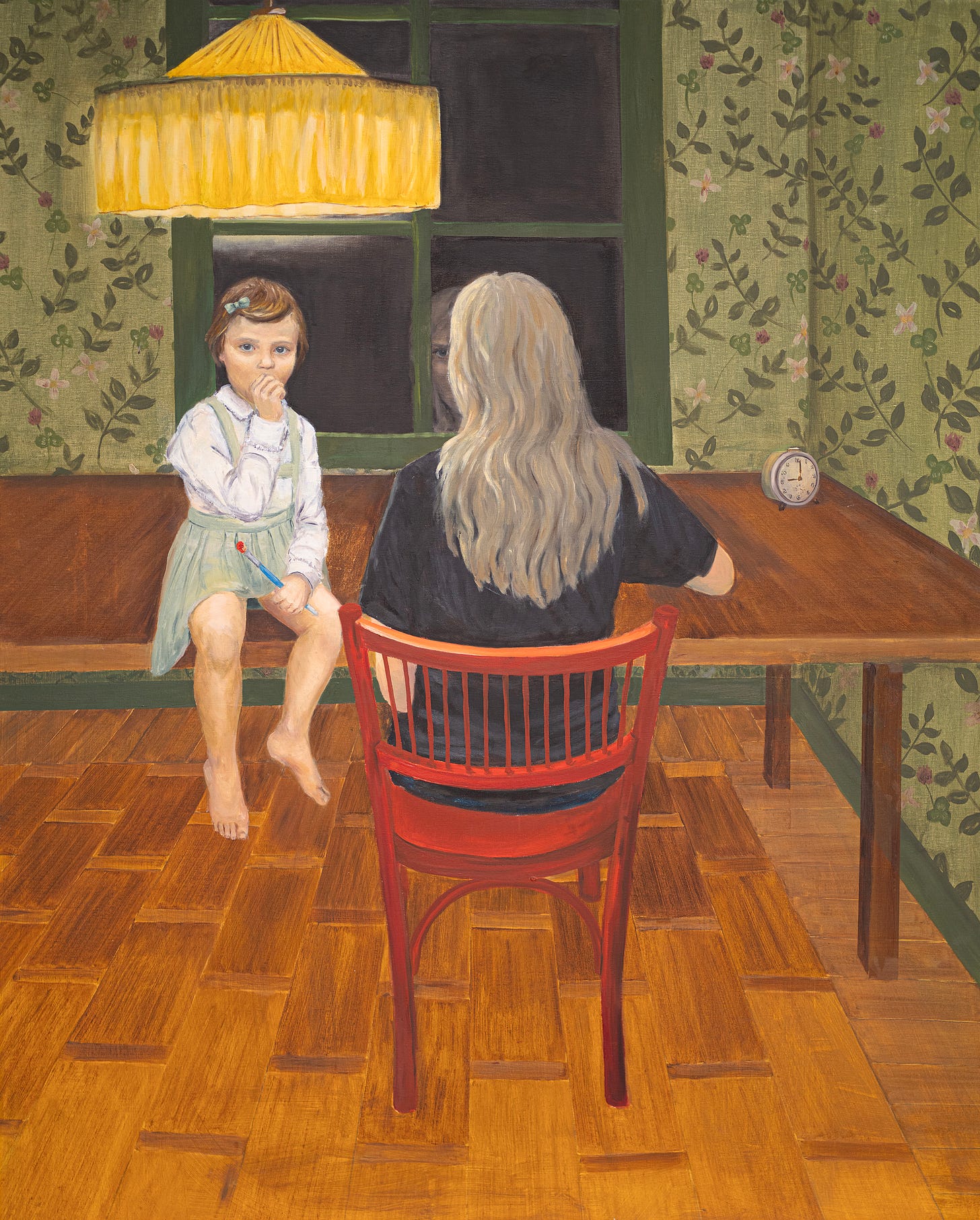

Sparre’s approach offers viewers the rare chance to reimagine family relationships outside of linear time, suggesting that healing can occur when we can ‘meet’ our family members in their younger selves. Imagine being four years old and meeting your grandmother at the same age—what questions would you ask? This provocative concept invites audiences to contemplate not only what could be learned but also how such dialogues might influence our understanding of family roles and emotional inheritance.

Rooted in her own experiences growing up as the fourth child of nine siblings, Sparre's work reflects her unique perspective on caregiving, where the traditional roles of parent and child blur. With her older siblings often acting as caregivers and, in turn, Sparre caring for her younger siblings, she experienced a dynamic in which generational roles shifted fluidly. These experiences have become a powerful source of inspiration in her work, questioning and reimagining what it means to nurture, connect, and understand across ages.

In painting the women of her family as ageless contemporaries, Sparre presents a nuanced commentary on the shared struggles, triumphs, and emotional legacies of motherhood, childhood, and beyond. Her work encourages viewers to consider their own familial histories, inspiring a journey inward to explore family dynamics and, perhaps, to find healing within themselves.

Tarantula Authors And Art: If we were doing this interview live in front of our readers, what would they see and/or how would they feel? Can you shortly introduce yourself to our subscribers?

Viola Sparre: I am in my Konstfack studio, sharing a room with a classmate who, like me, does incredibly colorful paintings. The space is a bit messy, but I think a painter's studio should be like that. With paint on the walls and floor, it is a well-organized chaos.

I am currently in the first year of my Master’s in Fine Arts at Konstfack. I’m usually pretty messy too; I have blue overalls on from an old cinema; they are also covered in oil paint. Before my BA in Fine Arts, I worked various odd jobs including as a silversmith and goldsmith. When I discovered painting as a medium for creative expression, I was hooked and haven’t worked with metal since.

I am the mother of three children. I am from Stockholm and was born into a large family; among nine siblings, I am number four.

Your paintings explore themes of childhood and motherhood, often blurring the

lines between them. You also said the line between your private life and art is thin. Who are your muses? As an artist, how do you strike a balance between revealing your muses and preserving their narratives?

My muses are definitely my children, but I also create many paintings in which my mother plays a prominent role. I usually portray them as small children, thus the portraits are often based on memories or stories from my family’s history. Even though I frequently blend the timelines together and have family members meet at the same age, I think that the family history plays a significant role.

Since I paint the people closest to me, the question of what is personal and what is private is crucial. I create personal images because that is what I am most interested in, whether I’m looking at other people’s art or working on my own. I think paintings become more interesting to me when there is this kind of nerve that arises when you can truly feel what happens on the canvas as the artist experiences it. I enjoy digging where I stand at the moment, but there are some downsides. I don’t want to invade anyone’s personal life. It’s important to state that the stories I tell through my artwork are my stories and my own truth.

Since I obviously can’t get inside someone’s head, I work from my own perspective and present the story as I see it. I suppose, as always, my portraits are a kind of self-portrait. I also never really tell the entire story; it is important for me that there is room for the viewer’s own interpretation. Therefore, I feel like “the answers,” if any, are separated from the artwork.

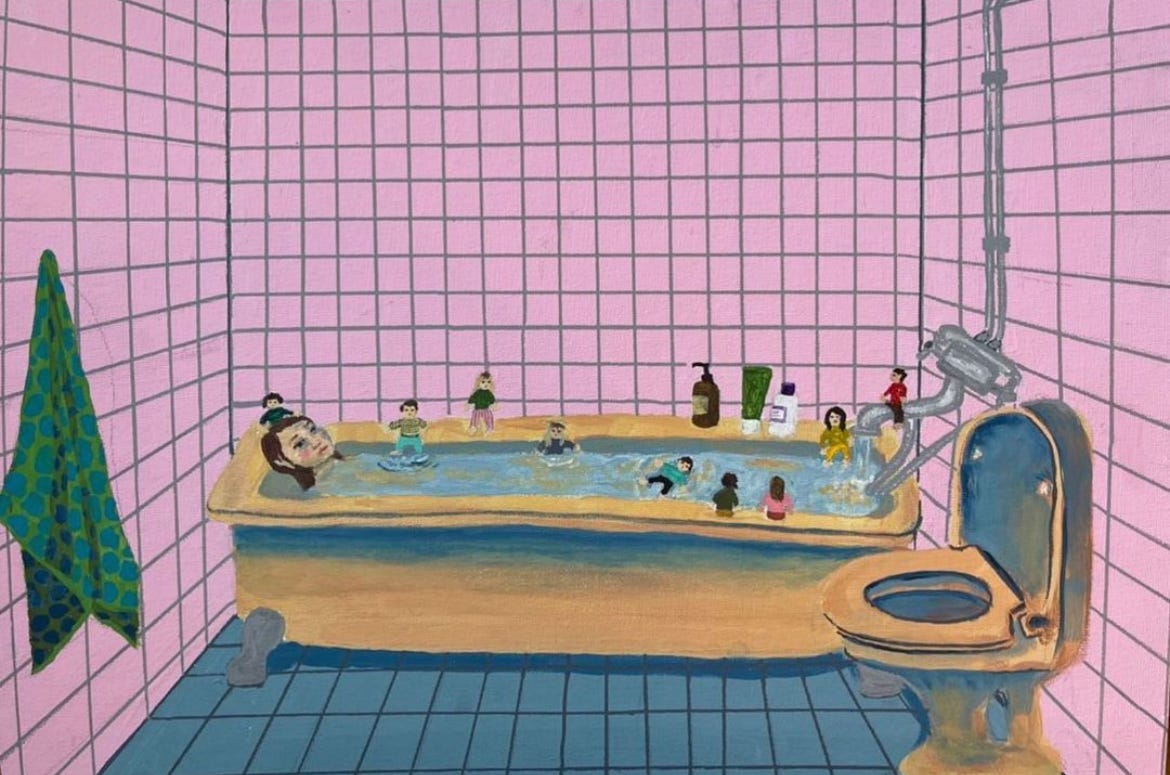

Your paintings depict your childhood through nine smaller figures surrounding a regular-sized child, evoking a sense of wonder, much like Gulliver and the Lilliputians. These figures appear in various intimate settings, such as bathtubs or sleeping together. Growing up with nine siblings must have shaped your perspective, and becoming a mother at a young age adds another layer to your experience. How do you navigate the challenges of privacy while balancing motherhood and your creative process, especially considering that many mother artists struggle to find the time, energy, and space to create?

Being the middle child in a large group of siblings shaped me in both positive and negative ways. I like to start my creative process by looking at family photos, and I found that my oldest sister, who was nine when I was born, is always the one holding me in them. We all play a maternal role for one another; the siblings raised each other because one or two parents cannot adequately care for nine children.

The painting I created with the small doll figures and the normal-sized girl was the first paintings I did. I was really inspired by Lena Cronqvist; she used to paint girls with dolls that symbolized her parents. Her paintings are very attention-grabbing and absurd, yet it was a powerful experience that changed how I view art. It shifted my perception of what art could be. So, I started painting these dolls as me and my siblings, with the girl representing my mother when she was a child. It was an opportunity for me to explore family roles and mother-child dynamics, but I feel like I have moved on from those paintings. I believe it is vital for any new artist to have a few idols to guide them in the beginning, but it is also important to let go and create your own artistic world.

When it comes to balancing my practice and motherhood, it is a tough question. I have read the book Mother Reader, which addresses several mothers' viewpoints on working in a creative field where you do not make much money and the work never stops. You’re never not working; the process continues in your mind. Additionally, there’s a continual feeling of guilt.

In my upbringing and in my life now, I’m rarely alone, so when I first got my own studio space in school, I was so happy, and I still am. Having my own room to think and create felt like such a luxury. However, I always feel compelled to spend as much time as possible with my children, resulting in a continual conflict. I believe I unconsciously paint my children to relieve the guilt of working on something that may not contribute financially but does take time away from them.

Previously in Tarantula: Authors And Art, we had an artist that used wallpaper to speak about female reproductive rights in Ireland. The patterns on your wallpapers, as well as carpets, even furniture, are well thought out. Can you tell us more about how you integrate interior design into your paintings?

With the exception of a few pieces of furniture, almost all of the interiors are fantasy and frequently occur to me while I paint. I want my paintings to exist in a sort of vacuum from the world outside. My preference is for the interiors to be independent of period and socioeconomic class. Nevertheless, I like working with symbols, whether they are well-known or ones that only I understand. I find it satisfying, much like looking for clues. For example, I often include a lot of flowers in my patterns, and the flowers themselves often represent or symbolize different things. Regarding the surroundings and patterns, my mother-in-law's artwork has greatly inspired me. She is an artist who frequently uses patterns in many contexts.

Another recurring image in your work is that of a bed, often set in a room or hospital. This brings to mind Frida Kahlo, who painted from her bed due to her injuries. How does the image of a bed resonate with your own experiences?

The bed is an interesting place for me. Although it should be a safe and restful environment, it is often a source of anxiety for many people. A person sleeping in becomes vulnerable and exposed because of the lack of control when you are sleeping.

I am currently reading a biography about Frida Kahlo’s life. I am deeply affected by her paintings of hospital environments. I have spent time in hospitals with my son, who was born with a rare and severe heart condition. I have a love-hate relationship with hospitals because they fill me with such gratitude—my son wouldn’t be alive if I hadn’t given birth to him at a hospital. But the hospital also scares me, as it constantly reminds me of the fragility of life.

In your paintings, we notice a distinct color palette that enhances the themes of childhood and motherhood. Can you share your thoughts on the colors you choose? What do they represent for you, and how do they contribute to the emotional depth of your work?

Working with colors appeals to me because of my background in metalworking. I have been inspired by cinema, especially by Wes Anderson's ability to bring life to the sets in his films through his vivid color palette. I like the idea of using bright colors as a kind of drop curtain for the darker themes that sometimes emerge in my works. I want the viewer to see beyond what they first encounter in the color palette. For me, colors are a good way to achieve balance in the narrative.

Your paintings capture distinct periods of development—childhood, motherhood, and puberty—while also encapsulating fleeting moments in time. What compels you to focus on these specific moments, and why do you feel it’s important to immortalize them in your art?

I want to investigate the question of how we become who we are. What shapes our personality and relationships with others? I believe that the answers to these questions can be found in our childhood and DNA. Therefore, I enjoy capturing moments in time where I was present, as well as instances before my time, to demonstrate how they may still effect me and my children through generational inheritance.

I also want to capture the innocence and adaptability of children and young people. I regard kids as witnesses of what goes on in the family home, and when they grow up, they will need to digest or evaluate their experiences. Children are malleable and can adapt to nearly anything in their desire for love, but they are also shaped by the environment in which they grow up, with little knowledge of anything else. I am attempting to return to that frame of mind while I capture youngsters through my eyes of an adult. It is vital to me to immortalize them because it gives them a sense of power, and I believe that it is important to consider children's minds.

In your newest exhibition, “Betraktare (Observers),” which opens on November 21st at the CF Hill Gallery in Stockholm, you explore themes of time travel. You mentioned wanting your mother to meet your children at various stages of their lives through your paintings. Can you share more about this new show and the ideas behind it?

I have always struggled with showing or portraying the psychological heritage; therefore I thought it would be interesting if my children or I could meet my mother as a child to help them better understand the psychological legacy. If the dynamic changes, maybe they will be more open to understanding one another. It also symbolizes that the traditional relationship between the responsible parent and the innocent child is not always right, and that the roles can change over time.

This exhibition will summarize many of the themes I have been working on over the last few years. There will be connections to the home environment, motherhood, and the complex relationships that exist within a family. Additionally, there will also be a clear focus on the viewer.

Are there any themes or subjects you’re particularly excited to explore in future projects? What’s on your artistic horizon?

I plan to continue working on the themes of motherhood and the home, but I am eager to delve deeper into magical realism and bring surrealism up a notch in my work. I think I would also like to concentrate more on my son's history as a subject and examine how worry and fear affect a person.

Where can our readers learn more about you?

I’m in the process of setting up a website, but soon, in time for my exhibition, you will be able to read a little about my work at CF Hill’s website.

Thank you Viola Sparre for sharing your artwork and process with us! If you are in Stockholm on November 20th, visit Sparre’s solo show at CF HIll Gallery.

ONLY TWO LEFT: Buy our print magazine by clicking on the following link

https://tarantulaauthorsandart.substack.com/publish/post/129709764

Emotional and beautiful art comes along with wonderful interview.