Muhammad Ali, The Artist

A conversation with Tarantula: Authors And Art's Inspiration for March, Muhammad Ali

I am late for the interview with Muhammad Ali, so our meeting started with a sense of urgency. We quickly get a coffee and head into his studio. It feels that there is much to say and no time to waste. As if time and space might slide away from underneath our feet at any given moment.

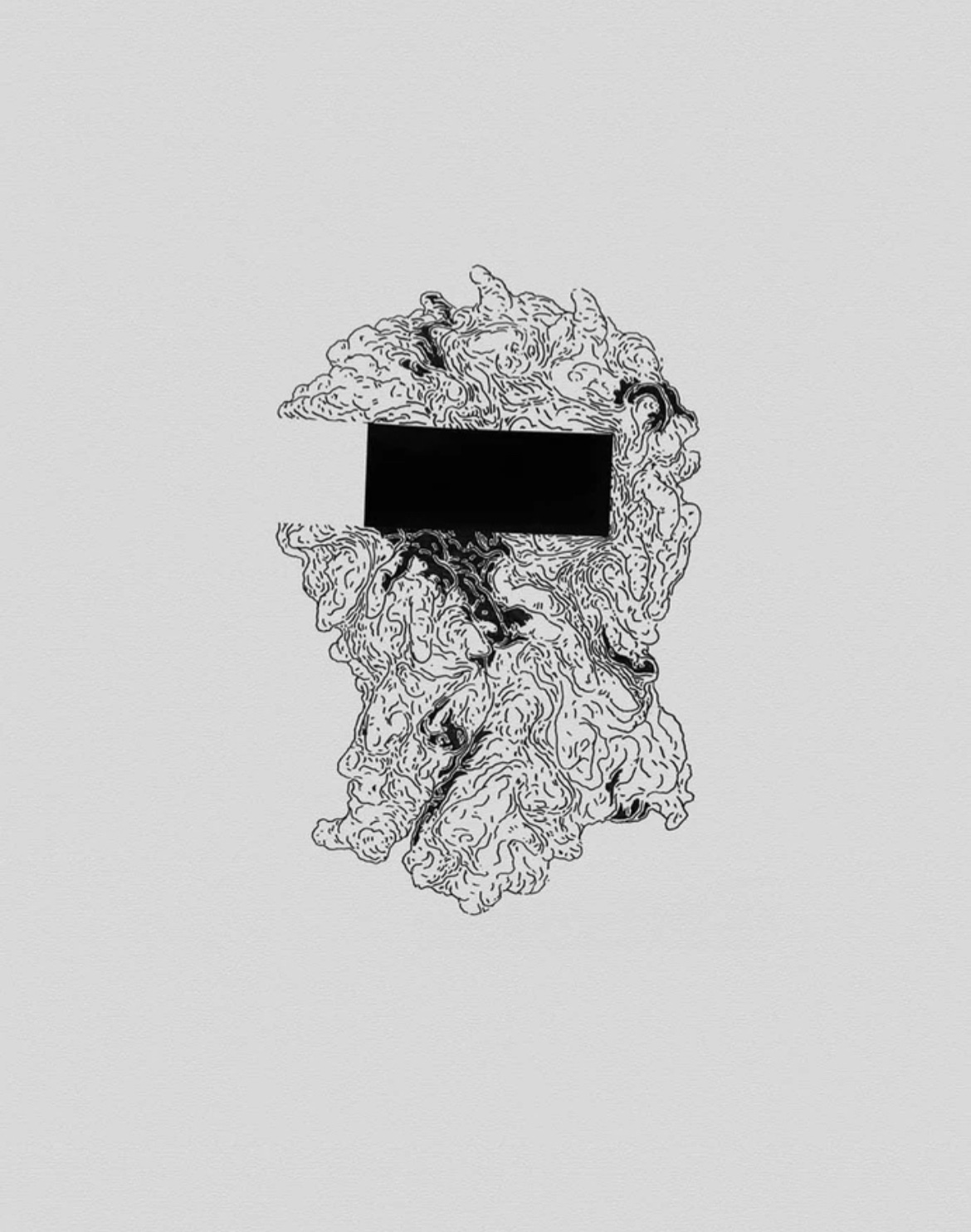

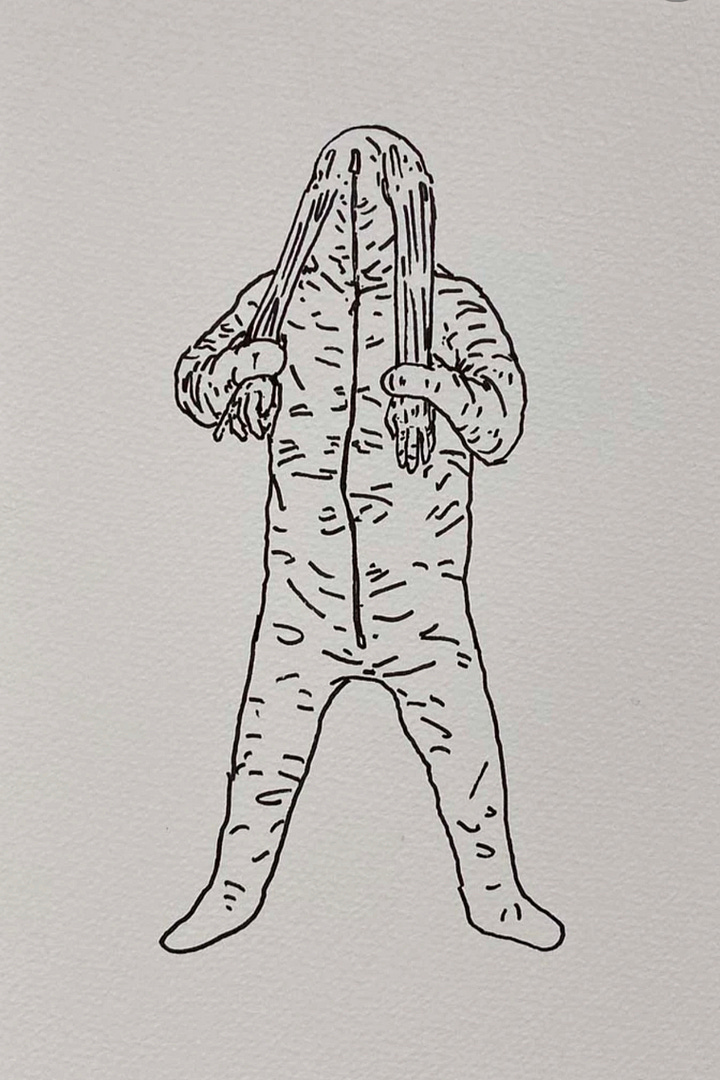

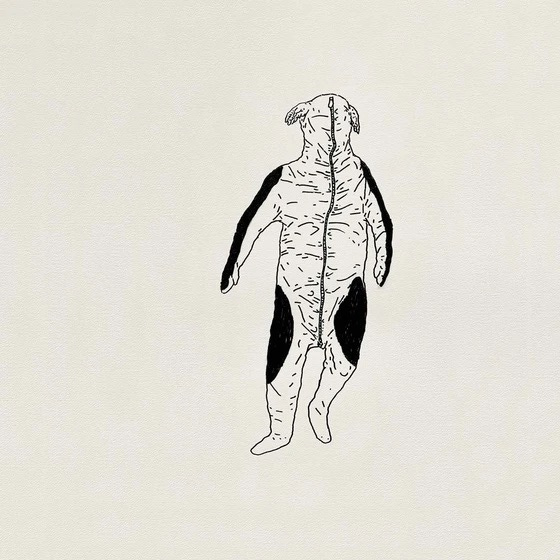

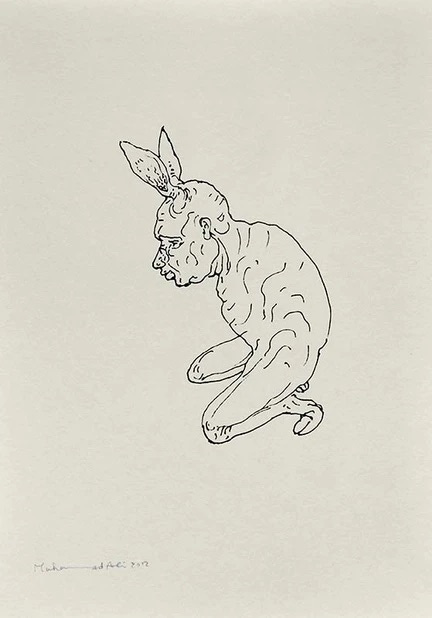

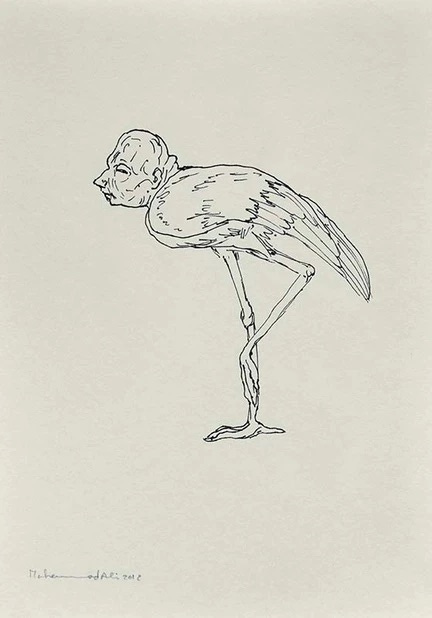

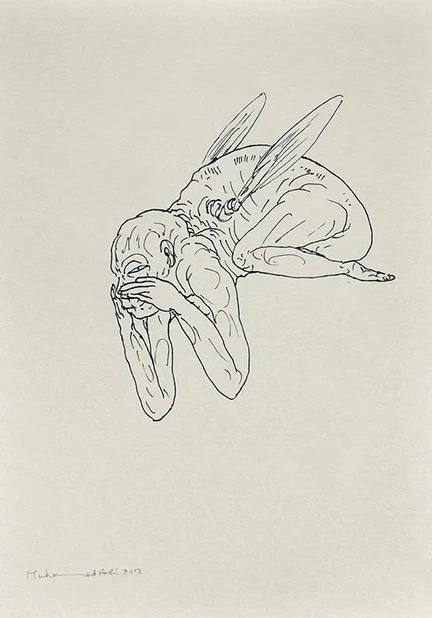

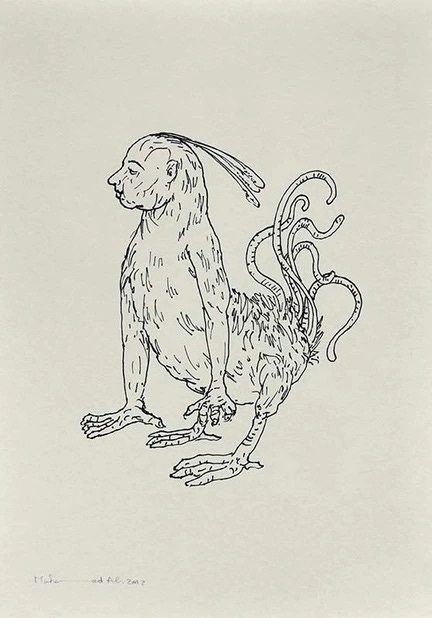

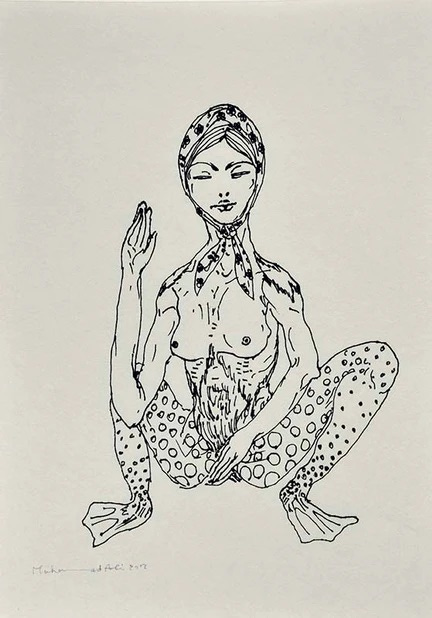

The artist opens his portfolio folder filled with black and white drawings, a mix of what looks like scribbles juxtaposed with perfect geometry. As I fumble with my phone to start recording, I realize that he has already began his story. I catch him mid sentence.

"... the story was about punishing those who wore masks. During a period when people began wearing masks, criminals were able to hide behind them, leading to increased crime. Those who used a mask went to jail and stayed isolated in a room for several years. The prisoners were unable to see their faces due to a broken mirror in the room, so I believe that eventually they forgot how their true faces looked.”

I wonder if the story he told is real or something the artist created. I quickly find out that it is a fragment of his imagination.

”I mean, who goes to jail for wearing a mask? These stories are all connected to the truths about people, power, and our perceptions of the world and ourselves.”

I finally catch up. The stories he is referring to are actually his drawings entitled “After Mask,” and possibly his entire body of work. But more than the conversation, I immediately understand that I am about to enter a realm between fact and fiction for the next hour, and that I am in for a treat.

Maja Milanovic: You use different mediums to create but your art is predominantly black and white with black blotches of ink. Short, staccato, thin lines show up throughout your body of work.

Muhammad Ali: Drawing is always there whether I do sculpture or kinetic work. For me, drawing is a way of writing. I'm not good at writing, so I use lines and myth as writing methods.

It almost feels as if you are creating your own letters and symbols, have you used them in other works?

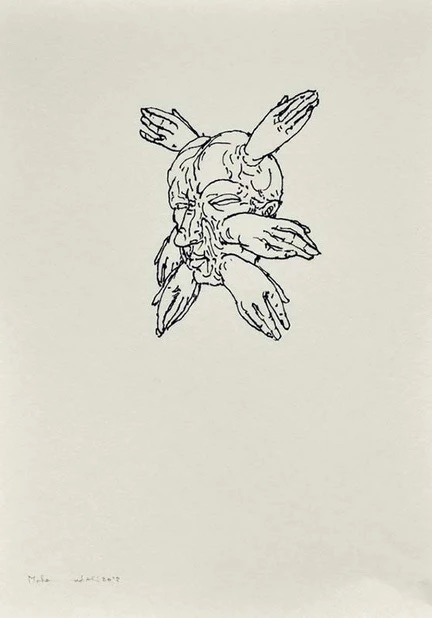

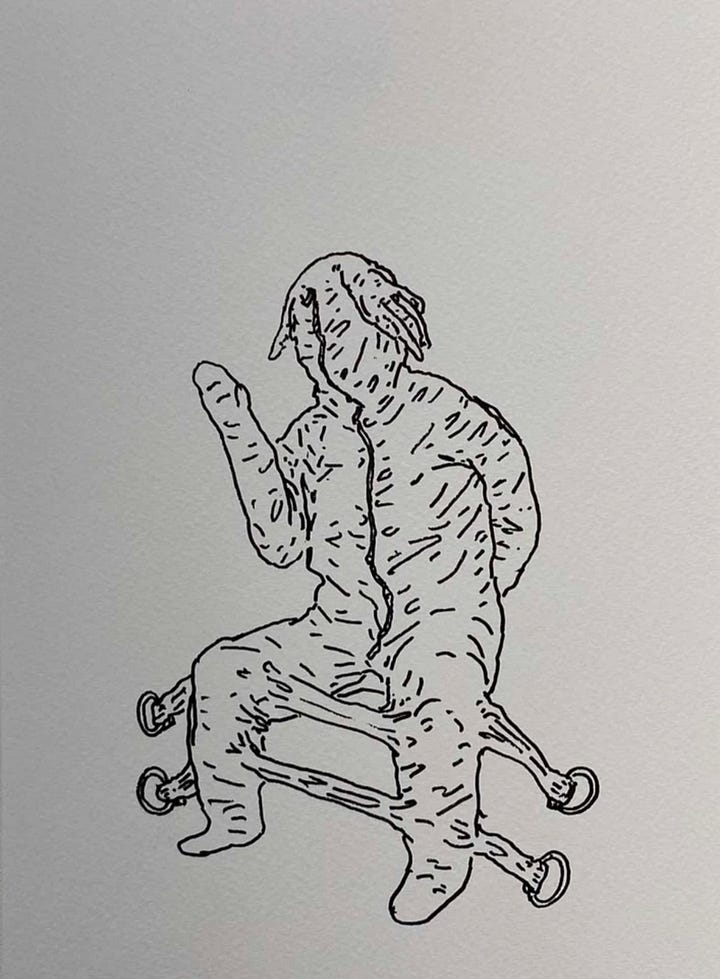

No. If you look closely, in addition to the lines, you see fingers, noses, hands, body parts, head parts.

Tell us about the symbolism behind the body parts.

It's about our physical deformities and our ignorance of them. According to a neuroscientist I read, the brain recognizes no parts of our body and is incapable of understanding language. However, when we repeat an action, it begins to see it as enjoyable.

I wonder if drawing these short thin lines over and over is meditative or painful for the brain?

It is cathartic. I am not only creating art, but also cleansing my body. My spirit. I usually become sick after I finish a project. So it's probably the opposite of meditation or another aspect of meditation because when I'm working I talk a lot to myself. It's more like writing than meditation.

As you draw, you are undoubtedly experiencing all of the emotions as well. One thing I noticed about your work is that it's really empathetic, as you seem to be attempting to convey to the viewer what the other characters in your drawings are going through.

While empathy is a strategy I use to try to connect with the audience, it is not a concept I use in my work. I don't want to narrow my attention to one subject. No, I would prefer to leave it up to interpretation rather than talk about what the outside world did to me. It's comparable to how displaced individuals appear, how they feel, or how you feel when you witness other people's suffering.

Another remarkable thing about your work, your figures look more like salamanders than humans because they don't have hair, they don't have specific characteristics.

They have cancer. A lot of my family died from cancer, my father, my sister's kids, so what I realized is that we become similar when dealing with extreme suffering. When we lose our hair, get chemical treatment, when the color of the skin changes, and the area around the eye.

Does this suffering also extend to war? I can't help but think of your series, “The Diary of a Roamer,” in which you drew what you saw while walking the streets of your town during the war. Many of the individuals depicted in these pieces share this cancer-like look.

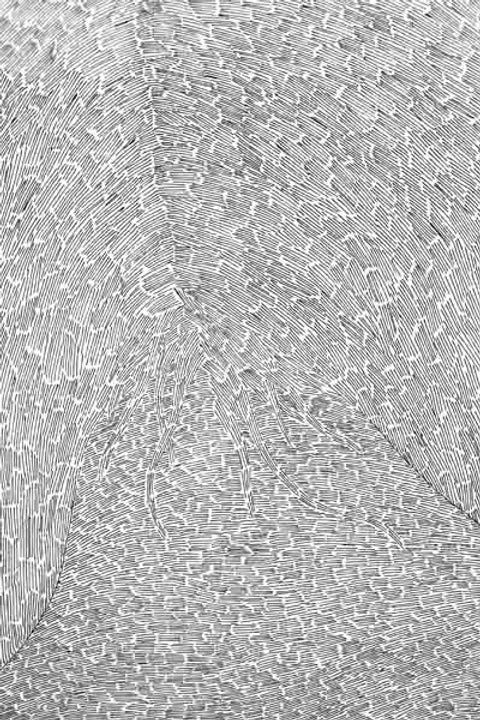

I actually started drawing these kind of figures before the war. In my “Catharsis” project, I created drawings that were two meters high and 150 wide, with very tiny details. I used a pen 0.02 and was making small lines about one centimeter. And in that project, there was actually some work with hair, but the hair was added onto the original hair of the character. I was trying to depict people as just "human" without mentioning things like "from where" or "whom" or "I've got" - just human.

You said the pencil was 0.5, the lines 1 cm long. Do you ever impose these constraints on yourself before you even begin working?

That is a good question. In that project, I gave myself limits: I will use this pen, no thicker, and the lines should not touch each other, therefore it ended up being one line moving in a specific way. It hurt because sometimes I felt like making a big line, but it wasn't allowed. Every 20 minutes or half an hour, I washed my hands with soap and water. Otherwise, it was not possible to create.

You created a ritual.

Indeed, and it has to do with the work. Cleaning your hands, cleaning your surroundings, cleaning your problem. And then there was no longer any pain in my hand. After that, I could resume my work. It's not only about the work itself; it's also about the process of creation.

I met you at the Juxtapose Art Festival in Aarhus where I experienced your VR project. Wearing the glasses, I felt reluctant to leave the captivating world you created. My initial impression of your artwork was that it evoked a sense of beauty. However, upon visiting your website and seeing your other work, I was surprised by its darker tone.

Sometimes it's about the presentation of the art as well. For example, if I show one of my drawings on an old wall in a dark factory, you would think "Oh, that's so dark. It's deep in the dark." But if I show it in a clean, calm room on a white wall, and add a little bit of perfume, then you would feel sympathetic to the same drawing.

My colleagues recorded me while I was immersed in your VR and I looked like I was dancing.

That's one of the reasons why I make it interactive, so that you can use your hand to move objects. In a way, the audience starts performing for my work. In a show in Algeria, I made a VR about one character AEIOU. The exhibition consisted of three parts: drawings, talking about the character and VR. I built a room where the audience could react to the character, interact and become the character. I laughed so much and was so glad about how the viewers reacted to him. Drawings of Aeiou are currently being exhibited at Studio 44 in Stockholm.

Aeiou is a character that you keep on returning to and exploring. Who is "Aeiou"?

Aeiou is everyone.

How did you come up with the name?

When I started working on that idea, I listened to music and read poems by Mahmoud Darwish, a Palestinian poet. In his book of poems, "I Don't Want This Poem To End: Early and Late Poems," I came across these lines:

Now, distance is the domain of the Swallow alone

Now, you are two, you are three, twenty,

A thousand, how should you know in your multiplicity who you are?Now, you were

Now, you will be

So know who you are...so as to be

So, I created this character Aeiou. I tried to name him by using many different methods like they do in art history, but it didn't work. For about three days, I was trying and repeating words, letters, and things to find the name. And what I discovered was that most of my trying was focused on the vowels, so I took international vowels, English vowels, that I think everyone in the world can understand, and created his name.

He's an existential character.

This character is unstable in his personality, in time and place. He can be anywhere at anytime, and he has no control over where he can stay. He can't control his emotions and he's playful, he's trying to enjoy his life but sometimes he finds himself in sad and very confusing situations that he doesn't want to be in and he tries to adapt. In another word, I can say, he is the psychological side of displaced people. Not only in war, but all kinds of displacements, because he is very open. Even if Aeiou accidentally finds himself in a box, he must adopt if he wishes to survive.

It's a bit absurd.

My work portrays the absurd as realism or pathaphysics. I make things really absurd in order to gain insight into reality that is beyond comprehension. The intention behind Aeiou is to make people believe that he might be them.

You also make diaries in order to understand your surroundings.

True, I make diaries.The Damascus diaries is one example.

That was during the war, right? 2012-2015. And then the project abruptly stops because you left.

Yes. It's currently on display as part of the Moderna Museet's new exhibition in Malmö.

I found the project fascinating because you captured people's behavior, moods, and how everything changes during that time. It's similar to a time capsule. In 500 years, what may someone learn from viewing your diary? Would they even believe that the events of the beginning of this century occurred?

In my diary, I have a piece titled "Post-1000 and One Night." We are aware that "The Thousand and One Nights" is a fairy tale and works of fiction. My art is created with the intention of being revisited, which is why I refer to it as "post." When they return, they may wonder themselves, "Is that what happened?" in the same way that the original stories did. They start to wonder if it's all made up since they can't believe how much violence is happening.

I would like to finish up with talking a little bit about your shows. You just had an opening at the Moderna Museet in Malmö titled “Unhealed,’” and the other at Studio 44 in Stockholm is “Nutopia.” Tell us a little bit about them.

The idea in “Unhealed” was to present what happened in the Arab world during the uprising. Something is still left unhealed in the aftermath because people had hope, they wanted to be free and thought that they would gain what they're asking for, but it went in the opposite direction.

In “Nutopia,;” I produced new work but the main subject is Aeiou. He fits in this exhibition perfectly as a citizen of this Utopian city. It's also about hope.

But you said that Aeiou represents the displaced person.

Hopefully, in Nutopia, there's a place for everyone, even him.

I finish recording, and Muhammad sits in his chair, looking almost relieved that the interview is over. Once, the artist mask is taken off and he settles back into his mundane body, I realize how hard he must work to portray himself as a human and an artist without constantly being judged from the outside by the burden that his birth nation has placed on him. That's when I decid not to write about his origin or his views on the world, but rather to let his artistic self emerge.

As we share some sweet pastries and continue to speak off the record as two displaced people, a glimpse of Aeiou appears. He is slightly more nervous than the artist, fidgeting and warm. It is time for the world to adopt and leave him alone.

For more information on Muhammad and his forthcoming events, visit his website: mhd-ali.com and Instagram Page @muhammad_ali_studio