If you are a regular or have just discovered Tarantula: Authors and Art, welcome. This May, we celebrate Meira Ahmemulić, a first-generation Swede whose art explores identity and belonging. Interviewed by photographer Sandra Vitaljić, herself a first-generation immigrant, their exchange deepened into a poignant dialogue, with Vitaljić responding through a heartfelt letter on shared experiences. If a friend forwarded you this article, welcome; if you like it, share it or why not subscribe?

Dear Meira,

When my partner and I decided to move to Sweden with our young children, we assumed we were as far as possible from the stereotype of immigrants we grew up with in Yugoslavia. Our limited childhood image of “gastarbajteri” (from German gäst arbeiter - guest worker) was of mostly uneducated, low-skilled men working in German factories and construction sites, often leaving their families behind. Sometimes, their wives accompanied them, but many children were left to be raised by grandparents. Parents sent money home and visited twice a year, bringing German candy, Coca-Cola cans, and other gifts. These things may seem trivial now, but in socialist Yugoslavia, foreign goods were rare luxuries.

Growing up, I considered myself lucky—I was born and raised in Pula, a coastal town near the Italian border, so we often travelled to Trieste to shop. As a teenager, I could buy jeans and T-shirts with English slogans, while others sought out LPs and cassette tapes. These were glimpses into the capitalist West, a world full of inspiring pop culture and infinite opportunities.

Most gastarbeiters lived simply, saving money to one day return home with a Mercedes and build a big family house to retire in. Many came back worn out, their health deteriorated by hard labour, reuniting with families they had grown estranged from. And then there were the political immigrants—Croatian nationalists, exiled and radicalised, who later in the 1990s donated money to support Croatian independence and its nationalistic party that came to power.

To cut a long story short, when my family landed at Arlanda on October 19th, 2018, we weren’t fully aware of the implications of our decision. I won’t go into detail about what brought us to Sweden—it’s a question I’ve had to answer more times than I can count, often leaving me feeling exposed and uneasy. What I will say is that we were not economic migrants chasing a better life. We had stable careers and financial security at home. I came in search of a homeland, which I could believe in—one that shared my values and welcomed my contributions. I was looking for a kind of utopia.

However, I quickly came to the realization that I was just “another immigrant,” regardless of my motives, my education, and my personal and professional competencies. Everything about me was reduced to that label—”invandrare.” Immigrant. I struggled with the indignity and the heavy connotations of that term.

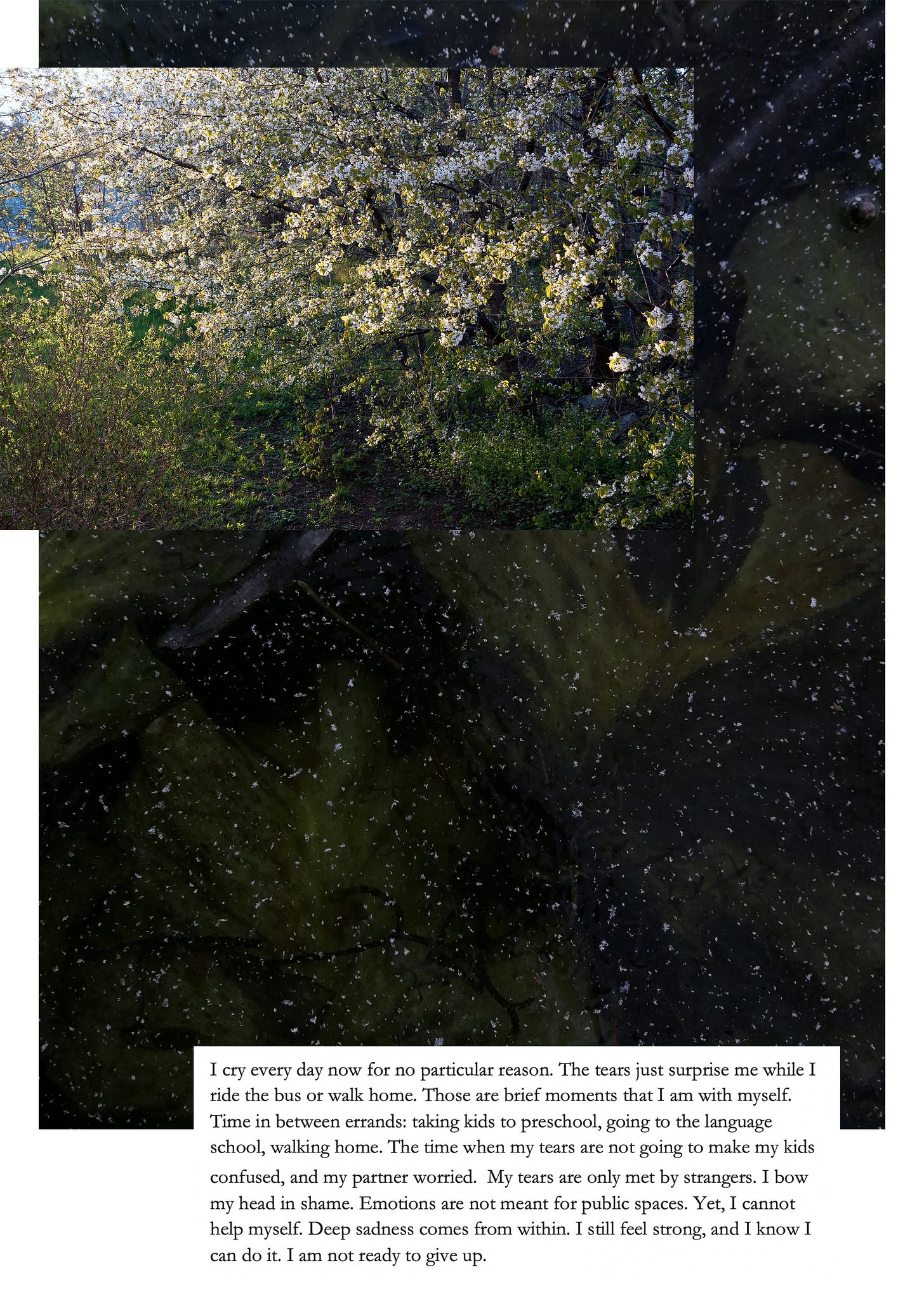

Then, I started writing. At first, it was just for myself—jotting down thoughts, emotions, and struggles. I had no one to talk to, and many of those thoughts seemed so small and ordinary, I wasn’t even sure they were worth voicing. But they were there, nonetheless.

Over time, I met other women and began documenting our conversations. What emerged was a collective diary, accompanied by my photographs and a herbarium I collected during the pandemic. As society shut down, those of us on the margins became even more excluded. To fill my lonely days and invert power dynamics, I pretended to be an explorer of a new land, documenting its flora—except that my herbarium didn’t list plant names. Instead, it captured the words of immigrant women, key terms describing their lived realities. This project evolved into the artwork I Just Greet Back—a tapestry of stories about dignity in precarious conditions. These narratives reflect a society’s inner workings, its cultural nuances, and its unspoken biases.

While researching migration, I discovered your work, dear Meira. I felt an immediate connection—not just because of our shared Yugoslavian background, but because, like you, I came from a working-class family, with no tradition of art or academia. When I decided to study photography, I had to explain to many relatives what I would actually do for a living. Despite that, my family supported me, even if they never fully understood what I was doing. Daring to dream beyond the world I knew was, in itself, a privilege. Access to knowledge is not universal. Who gets to be an artist is defined by privilege. Despite my success, my journey was always shadowed by self-doubt, low self-esteem, and the persistent feeling of never being enough.

Meira Ahmemulić, Invasiva arter / Invasive species, 2022, in Swedish

Just like you, Meira, I was interested in invasive species that were often seen as a metaphor for immigrants. When the Swedish woman in your powerful narration in the video work Invasiva arter / Invasive species shouts: “Alla krabbor som inte är svenska ska krossas! - All crabs that are not Swedish should be crushed!" I am teleported to the bus in Nacka one afternoon when I picked up my kids from preschool. They were sitting comfortably in the bike stroller I used to transport them sometimes by bike, often by walking, or riding a bus, when a Swedish women entered at the bus stop and insisted that I get off the bus because my stroller was not suitable for the bus. The bus driver resolved the dispute by stating that there is nothing wrong with my stroller and that I have an equal right to ride the bus with it as everyone else. I was shocked by this unprovoked attack, but even more by comments from the woman and others on the bus that "Hon pratar inte Svenska"/ She doesn't speak Swedish”, as if I was doing something wrong or am incapable of following the “rules." Pushing the stroller home, I cried—not because of her rudeness, but because of my own silence that swallowed me whole.

Giving up what I'd accomplished in Croatia was not an easy decision. But I felt like I had done everything I could there, and I was curious, hungry to explore new paths and continue learning. Artists often carry a strong sense of identity, but I had to reinvent myself. I am more than an artist or educator, roles I held in my homeland, working as a university professor for the past fifteen years before my departure. The most important role I’ve taken on is that of a mother—a role often romanticized or imposed as a woman’s ultimate fulfillment. I never bought into that narrative. My partner and I became parents when we felt ready, in our 40s, and it turned our lives upside down. Suddenly, I was questioning everything—my values, my choices, my identity.

Leaving the economic stability of my career and social network made me vulnerable in ways I had never experienced. Art doesn't come first when it doesn't pay the bills. My education meant nothing when I struggled to help my first-grader with homework in Swedish. My children began to notice my low social status, my isolation. Every holiday was just the four of us at the dining table. I began to question the potential harm that this social seclusion could cause to the kids. They are learning through social interaction. Would they be better off in the country I left behind—a place with fewer resources, stuck in patriarchy and nationalism, but where I had a high social status and social and personal network?

I began to wonder: How can I be the best parent if I am consumed by humiliation, masked as political correctness but rooted in systemic exclusion? Humiliation from not being able to find adequate work. From being repeatedly denied rights by government agencies. From never being enough.

That humiliation that drives so many into illness and depression.

In 2021, the exhibition Mami: ama: mödrar opened at Botkyrka Konsthall, curated by Emma Domínguez and Macarena Dusant. The show and accompanying book were the result of a collective effort by nine artists, reflecting on how their immigrant mothers' lives were shaped by low-paid, physically demanding work that often led to illness, and then further, to the denial of their rights to proper health care and sickness benefits. During the book launch, I wept, recognising my future in those stories, and my children in the youth of Fittja who read poems about their own mothers.

When I started I Just Greet Back, many advised me to “go to Botkyrka” to work there on the project. That suggestion frustrated me. It revealed society’s narrow view of immigrants and reduction to the outskirts: where they/we supposedly live, what stories they/we ought to tell. None of the women I interviewed lived there. Our backgrounds and educations differed, but society’s eyes we were all the same. For some, the narratives we share are just another conventional immigrant story similar to many others all over the world. But I refuse to keep it to myself, I refuse this normalization of humiliation, inequality and injustice. I refuse to take it as it is.

It is not about us versus them, and it is not about complaining. It is about making visible our emotions, thoughts and struggles that often come from our own demons and insecurities, enforced by exclusion and inequality. How many of us are hesitant to speak our mother tongues in public, not to expose ourselves and draw attention... How many families have broken apart, with partners growing distant in silence, each burdened by heavy loads, unable even to support one another… How many gave up their dreams, accepting to be cleaners, taxi drivers, gardeners and assistant nurses despite their university education, just to make a living?

While working on the project, I encountered the Swedish Institute’s publication Sweden – A Country Less Ordinary, which is a glossy depiction of an idealized Sweden. The Swedish Institute is a public agency that deals with the public image of Sweden and is responsible for creating and maintaining "The Sweden Brand." But after living here, I realized I had to intervene in that narrative. So, I sewed pages shut or inserted immigrant women’s stories within the covers of the magazine. I dared to ask who has access to this dreamland of "sustainability, innovation and democracy."

As I write to you, Meira, I am also preparing yet another job application. I remind myself that I’m not ready to give up. I chose Sweden as my home. And I believe that everyone should have the right to choose. In a world shaped by war, climate change, economic shifts, and migration, the ability to live where you wish should not be a privilege, but a human right. The Western world, having built its wealth on exploitation, must stop defending its way of life as sacred, especially when it never respected the ways of life in the places it once conquered. With so many people with all kinds of backgrounds everywhere in the world, I find nation-states and national identities outdated.

The other day, while we were driving back from a trip to Tyresta, I spotted a gathering on one of the bridges across the highway. I was preparing to draw my children's attention to the protest that I thought might be a protest against the ongoing genocide in Gaza, but in the last moment, I remained speechless. Men, standing with their faces masked, held a banner with the words "Vita arbetare byggde detta land / White workers build this country." I really wanted to show them your aunt's finger, Meira.

Dear Meira, we never met in person, but I hope we will. We communicate in Swedish, despite our shared Yugoslav roots. One language must win. Interestingly enough, my children embraced their international identity and introduced English as one of the three languages they speak. I suspect English is going to win.

Your work spoke to me the moment I saw it. In all your video works, your kind and soft voice speaks so loudly. I reached out to you only recently, but I carry so many unasked questions. More than anything, I think I just need a hug from one artist and mother to another. I need you to tell me that my kids will be okay. That they will become whatever they want, despite the inequalities we both see so clearly.

We are of the same generation, but I see you as my children’s future. You are what I hope they will become. I am a first-generation immigrant like your parents. I hope you can tell me everything will be alright. And I want to hug you, for every person who ever shouted: "Krossa alla krabbor som inte är svenska! "

Yours, sincerely,

Sandra