We'd like to welcome you to ‘Shortcuts,' our end-of-month 6-question interview on our Substack platform, followed by a six-day daily takeover of our Instagram account by the featured artists and galleries. Please take a moment to click here to subscribe to our Instagram if you haven't already. Now, without further ado, please welcome artist Glorija Lizde.

Glorija Lizde is a Croatian visual artist whose work explores the intricate realms of memory, inheritance, and family ties. Born in Split in 1991, and educated in Film and Video at the Arts Academy in Split, later specialising in Photography at the Academy of Dramatic Art in Zagreb, Lizde creates deeply personal yet engaging visual narratives that often merge private history with broader social and political themes.

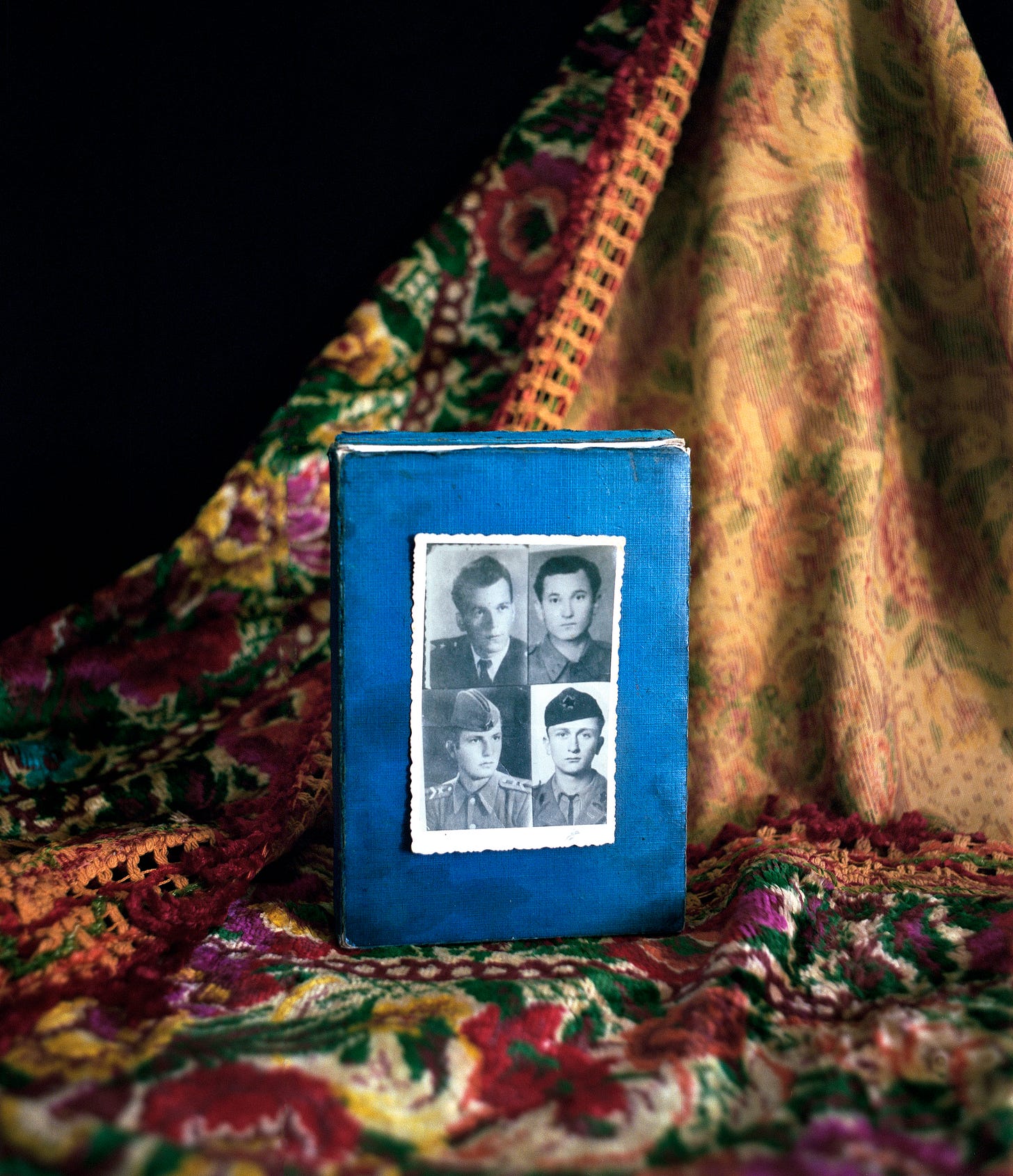

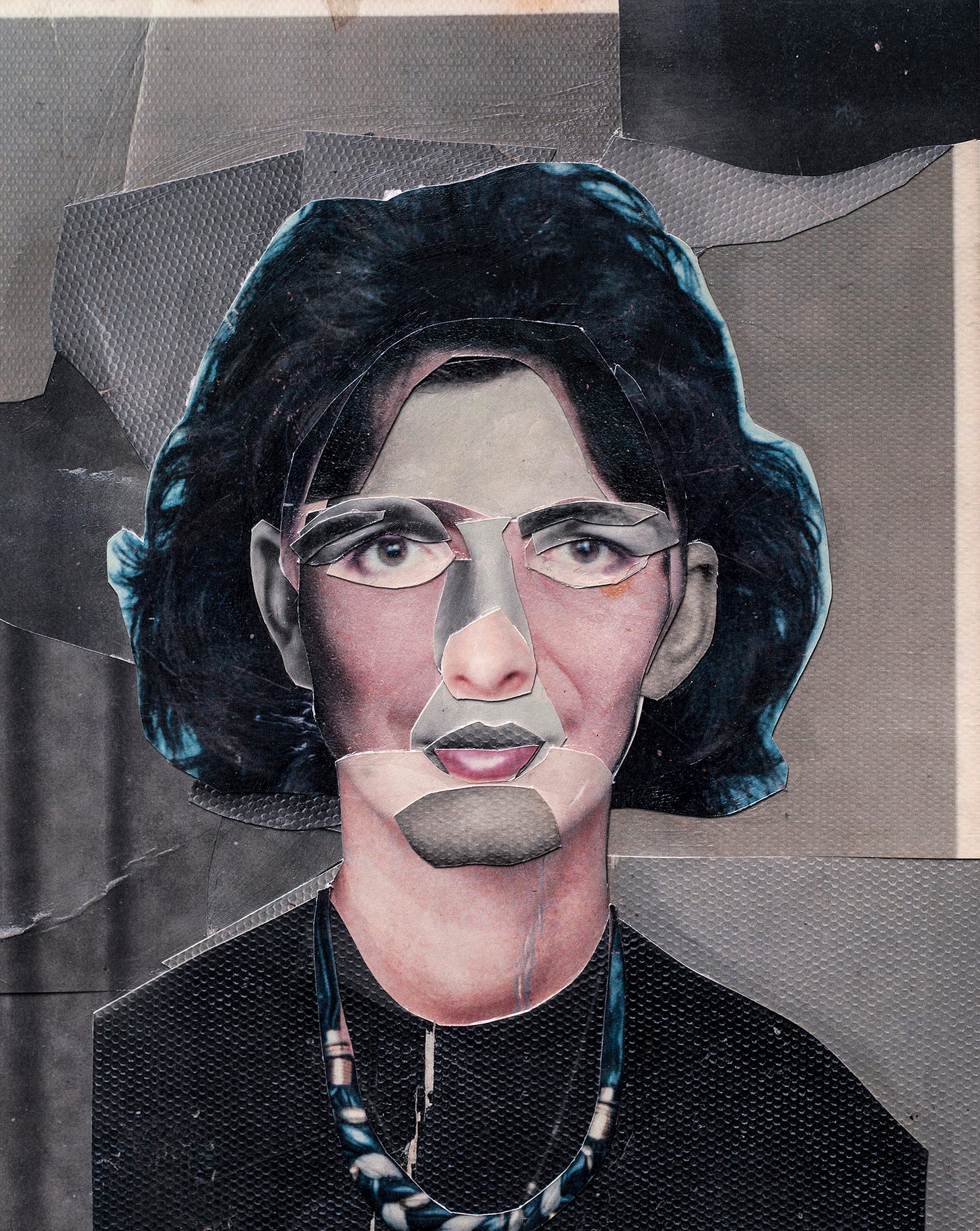

Her approach is highly research-based and intuitive, often beginning long before the camera is used. She works from sketchbooks filled with collected articles, films, fragments of thoughts, and references that shape her ideas over time. Each project builds upon the previous ones, forming a dynamic visual dialogue about the enduring nature of memory and the layers of personal and historical inheritance. Lizde frequently reflects on her own family history, as exemplified by projects like Fearless Youth, which retraces her grandfather’s experiences during the Second World War through a mixture of landscape, self-portraiture, and still life. Her more conceptual series, I Swallowed My Dream, draws on archival photographs of women diagnosed with hysteria, exploring themes of repression, gender, and the body through a feminist perspective.

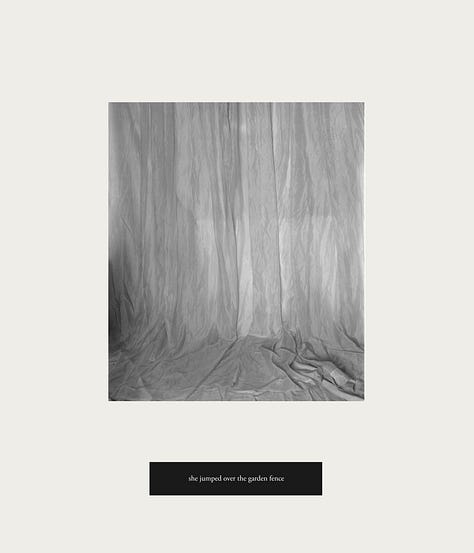

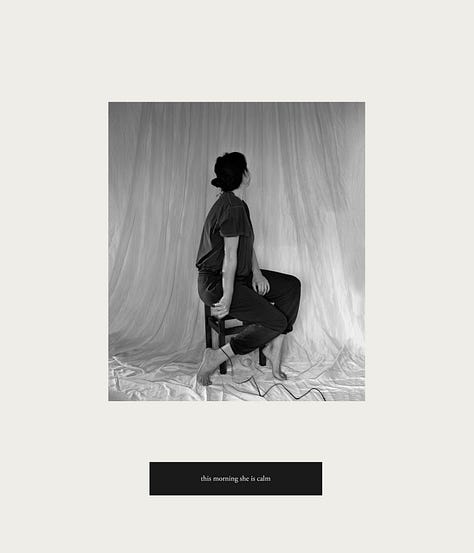

Throughout her work, Lizde is attracted to the tension between subject matter and execution—using tenderness and visual restraint to tell stories rooted in trauma, discomfort, or unease. This contrast creates space for empathy and reflection, offering viewers an emotional entry point into difficult or suppressed histories.

Glorija Lizde’s photographs have been exhibited widely, from New York to Athens, and are included in institutional collections such as the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb and the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts in Japan. She was nominated for the prestigious World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass in 2020 and selected for the Parallel – European Photo Based Platform, an international program for emerging artists, in both 2018 and 2021. In 2022, she was awarded the Dr. Éva Kahán Foundation Scholarship and Residency and received the Radoslav Putar Award, which recognised her as Croatia’s most outstanding young visual artist.

In this conversation, we explore the underlying themes of her practice—the emotional architectures, intellectual frameworks, and subtle strategies through which she reclaims and reinterprets inherited narratives.

What conversations do you hope your work will spark?

I try to make my work primarily for myself, I believe there is always someone who will connect with it. I often begin with something I want to bring to light, something overlooked, silenced, or forgotten. These are usually narratives that haven’t been given enough space in public discourse. Through my work, I try to reexamine and recreate them, delve deeper, and see what surfaces.

I start with a memory, or with an individual I feel a connection to, and explore the parts that feel unclear or unresolved. I want to weave personal memory into the broader public narrative, to make space for overlooked histories and hidden stories.

I hope that the work sparks empathy, that it encourages viewers to think not only about others, but also about the complexities of family relationships, memory, and the ways we reconcile personal and collective experience. I search for stories that I believe need to be out there. I hope that my work makes viewers think about people and situations left out of dominant narratives, the relationships we don’t talk about, and the struggles that affect us.

Could you describe your creative process? Tell us about one of your projects

My work is research-oriented most of the time, it’s an important process for me since I like to prepare before moving into actually making photographs. I keep sketchbooks in which I collect everything that resonates with me; articles, books, films, references or fragments of thoughts or ideas that cross my mind. I find this time tracking very important as some ideas seem powerful at first but lose that strength over time, while others stay with me and resurface later. In that way, each of my projects grows out of the previous ones, there’s a thread that connects them all.

For example, I Swallowed My Dream developed from a set of archival photographs of women diagnosed with hysteria, which I first encountered six or seven years before I even considered making work around them. At the time, I was drawn to the images but didn’t yet know how to approach them. Eventually, I began studying them closely and started collecting and saving related material—photographs, illustrations, paintings, posters, and medical articles focused on hysteria, as well as texts examining the relationship between photography and psychiatry, particularly the ethical implications of photographing patients, mainly women, in medical settings.

As the project developed, I began sketching photographs and planned the setting and equipment for the images. I then created a series of self-portraits, carefully reconstructing the poses of female patients found in the photographs while holding the shutter release myself. It’s an object I consider important in the images, as it disrupts the dynamic between photographer and subject. Once I developed the negatives, I felt something was still missing. I returned to my research folders and began rereading medical journals and patient reports. That’s when I realized I needed to include texts, and excerpts from the clinical descriptions of patients' behaviors written by doctors. In this work I also produced a research booklet, compiling the found photographs and historical illustrations. It was a way to rewrite history, to make my own archive of hysteria.

How does your studio or workspace (physical or mental) look like?

I work from home, which can be challenging at times, but it also gives me the freedom to work whenever I want. Most of my time is spent planning and researching, often in the evenings or late at night when everything feels calm and quiet. While I would love to have a dedicated studio space, I’ve grown to appreciate the fluid rhythm of working from home —pausing to cook, folding laundry, and then drifting back into work. These small breaks, filled with repetitive, almost automatic tasks, often become moments of unexpected clarity. It’s the same thing with driving, I love driving long distances, the body is already busy with something so the mind can wander. It gives me time to process and absorb what I’ve been reading or uncovering, letting ideas settle, shift, and take shape.

Is your art influenced by where you were born or live now?

It is, but I’d say I’m more influenced by the people and things closest to me than by the place itself. My work stems from the personal—my family, memories, familiar objects and spaces, the things that shaped me and that I return to again and again in my practice. These elements trigger something internal that I feel compelled to explore through art.

Creating work outside of the place where I was born has always been a challenge, whether during residencies or while living in Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, where I studied. I always felt I needed to be at home to produce something.

This sense of geographic and emotional connection is perhaps most evident in my project Fearless Youth, which documents my grandfather’s experience during the Second World War. I photographed his warpath throughout former Yugoslavia, places which are burdened by history and marked by traumatic events and developed the work further through a series of self-portraits and still lives. In these photographs, I reinterpreted the personal objects that belonged to my grandfather as well as the war memorabilia he left behind. It was a way for me to weave an intimate and subjective story into a public narrative about the wars that have shaped this region.

Who are some of your most important female (womxn) sources of inspiration and influence?

I’ve always loved and appreciated the work of female photographers such as Cindy Sherman, Jo Spence, Francesca Woodman, Elina Brotherus etc. Each of them engages with the self through self-portraits, personal narratives, role-playing, or performative gestures. I’m drawn to the works that have strong contrast like the works of Louise Bourgeois or Paula Rego who uses soft pastels but her subjects are unsettling.

I am very inspired by the writings of Annie Ernaux and the works of Sophie Calle. Both of their works are methodical, almost clinically detached, yet intimacy and tenderness are always present, subtly permeating the work.

I’ve always been drawn to the idea that something harsh, traumatic or disquieting can be shown in a gentle and tender way, that meaning stands in opposition to the way the work is executed. I think there is something very powerful and compelling in expressing trauma or discomfort through tenderness, it opens up space for empathy and reflection.

What personally or professionally excites, worries, or keeps you connected?

There’s so much happening in the world right now that’s deeply worrying and of course, there are always personal and private concerns as well. In the midst of all that, my work feels like one of the few solitary spaces where I can detach, reflect, and do something for myself. And if the work resonates with others, if it sparks dialogue or creates a shared sense of experience, then that’s a meaningful extension of it.

I’m always thinking about the next project, researching, experimenting, and figuring out how to make the work. I truly just enjoy being in the process, by myself, that’s something I look forward to every day. Even when it’s frustrating or not coming together, it’s one of the few things I feel I have full agency over. I can step away or return to it on my terms, and it will still be there. That gives me comfort and meaning.

It’s also why I love photography; it’s a solitary process. I am the only one involved in it and I can always decide if the work makes sense or not, if it should be brought out into public or not. It’s a way for me to handle and process things, memories and emotions; it’s a tool for personal growth.

For further information about Glorija Lizde, please visit her website and Insta pages, but first, spend the next week with Maria by following her takeover of our Instagram page!