We'd like to welcome you to our new column 'Shortcuts' which will be published at the end of each month, in which we'll hand over our Instagram account to artists, galleries and artist-led organizations. The week will begin with a 6-question interview on our Substack platform, followed by six days of daily Instagram postings by the artists/galleries, in which the artists will freely publish one of their works in addition to their own thoughts. We at Tarantula: Authors And Art, along with you, our readers, get to sit back and enjoy the daily surprise of discovering each new work of art. Please take a moment to click here to subscribe to our Instagram if you haven't already. Now, without further ado, please welcome Shadman Shahid.

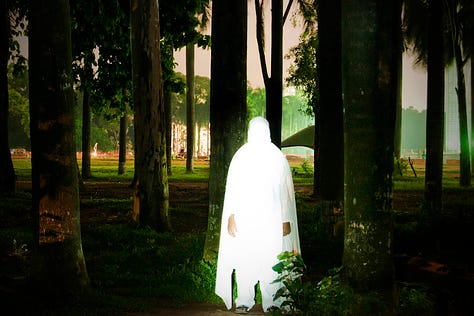

Photography has always been perceived as an accurate reflection of the reality around us, even though we are aware of it's manipulative potential. As a result, using photography for exploring the immaterial isn't an obvious choice.

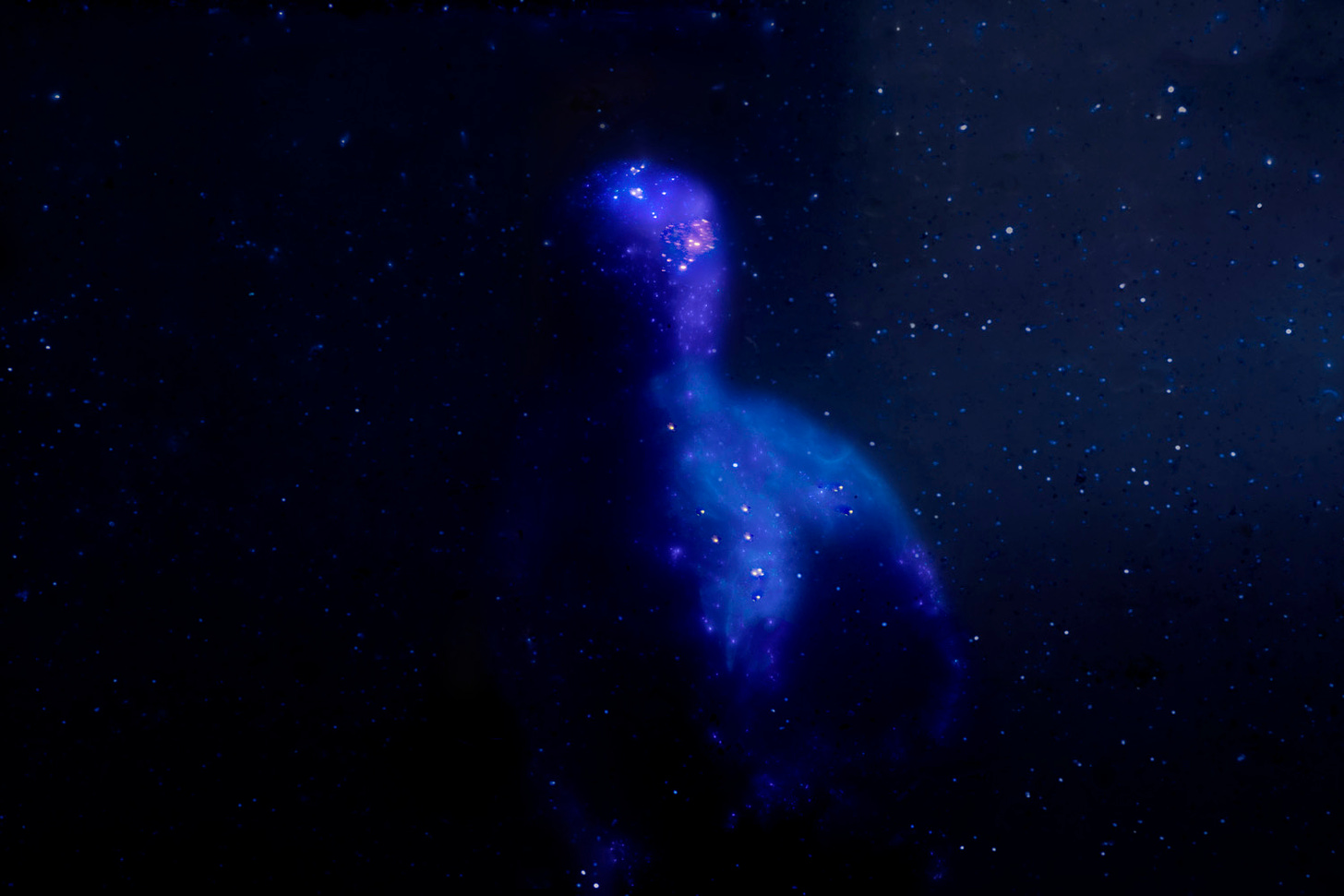

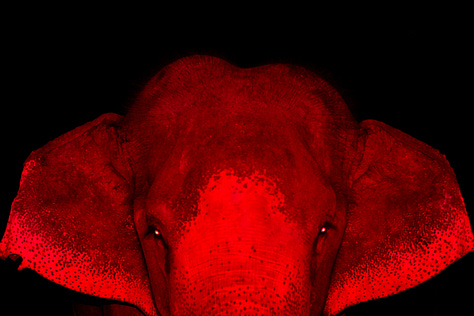

The title of the work by Bangladeshi photographer Shadman Shahid, Ajna, means "the eye that sees the immaterial" in Sanskrit. With "Ajna," Shahid is on a quest for self-exploration and expression while condensing many moments into one. Using long exposures, bright, striking colours and darkness, he chooses magic realism as his story-telling method.

His other works, which explore subjects like ghost cities in China or the life on St.Martin Island, are not as colourfully saturated. The content of the work always drives his aesthetic.Working on the thin line between documentary and fiction, he has brought a different mindset to documentary photography.

Shadman Shahid is currently based in the Netherlands, where he is working on personal projects while also teaching at the Royal Academy of Art in Hague. Before moving to the Netherlands, he was a lecturer at the renowned Pathshala South Asian Media Institute in Dhaka.

What conversations do you hope your work will spark?

It’s not easy for me to say definitively as I strive to have a balance with how directed I want the audience experience to be. There is a set of questions regarding the medium of photography and its relationship with our reality ever present in my works, but I feel that is only visible when one looks at my practice as a whole. I would say thematically my body of work is diverse, so each time I speak about something different, the scope of conversations changes. In 'Ajna,' the piece I am presenting here, I want the audience to engage in an intrapersonal dialogue. I will let the images decide what conversations they should provoke.

Could you describe your creative process?

I would say it is explorative, intuitive and organic. I start with a framework, of course, but one with malleable boundaries and within that, I let my ideas and creations grow intuitively. But at the same time, I am a big believer in limitations as a boon to the creative process. Limitations of space, time, social constructs, the body, and the camera are all useful and integral to my creative process. This work, for example, started due to my photographic curiosities. I was curious to what extent photography, a medium that is so chained to material reality, can mediate immaterial imagination. I was also fascinated by the relationship of shutter speed with the flow of time, more specifically, how slow shutter speeds condense multiple moments into one. These curiosities set the parameters for the project within which it was able to grow organically.

How does your studio or workspace (physical or mental) look like?

My workspace at the moment is in a small room in my house in the Hague, which is about six square meters in size. When you enter through the door, a wobbly, old table is on your left. Beside that is a small shelf which has my books, but only the ones I have gathered after moving to the Netherlands. There is a small bed on one side of the room where I lie down to read and think. The walls are filled with my students’ photographs that they have gifted me over the years. There are two boxes on the floor filled with my newborn’s clothes. On one of the walls, there is a whiteboard with the research question for my next work written. It says, “To what extent can photographic fiction address the absent reality of the colonial British Raj in Bengal?” Below that, there is a reminder to read Walter Benjamin’s words on the incompleteness of History. The window in the room is tiny and depressing, but there is a hazy skylight, which helps.

Is your art influenced by where you were born or live now?

Yes, absolutely. The space I inhabit, its geographical qualities, the landscapes, and the historical, political and cultural aspects all shape my identity and my perspective, which in turn shapes the art I create. For example, in Ajna (and in all my works, actually), I use magic realistic tropes, a genre that is born from our region of the world. This way of storytelling, where magic and reality seamlessly blend into each other to form a singular narrative, has been pivotal for us to understand and process reality. The aesthetic choices are a reflection of our limitations as well as our visual language that has developed over time. The work also reflects on the existential philosophical questions that have kept our region's philosophers, artists and storytellers busy for many hundreds of years. So yes, I am heavily influenced by where I was born.

Who are some of your most important female (womxn) sources of inspiration and influence?

There are too many, so perhaps a good idea would be to stay within the field of photography. Sayeeda Khanam was one of the first female Bengali photographers. She played a massive role in documenting the liberation war of 1971 and is an inspiration to all Bangladeshi photographers. Dayanita Singh is greatly influential in our parts of the world. I am in love with Vanessa Winship’s works and also Shirin Neshat’s. I find the practices of Newsha Tavakolian and Andrea Stultiens inspiring and exemplary.

What personally or professionally excites, worries, or keeps you connected?

To speak very broadly and generally, I am worried about the loss of humanity in human beings. Perhaps we are collectively too tired and overwhelmed to stay human. I think we need to slow down, take a break, a moment to rest, regain our strength and restore the humanity within us.

What excites me is how the scope for collaborations and collective movements has increased dramatically over the last few years. This opens up all sorts of possibilities for reshaping our world.

Shadman Shahid Art Exhibition

For further information about Shadman Shahid, please go to his website, but first spend the next week with Shadman Shahid by joining our Instagram page!