We'd like to welcome you to ‘Shortcuts,' our end-of-month 6-question interview on our Substack platform, followed by a six-day daily takeover of our Instagram account by the featured artists and galleries. Please take a moment to click here to subscribe to our Instagram if you haven't already. Now, without further ado, please welcome Ghana-based artist Ulla Deventer.

Sex workers, abuse, violence and horses were the subjects that Ulla Deventer focused on for the longest time. At first glance, the transition from dealing with the precarious living conditions of female sex workers to photographing horses is not an obvious one. Capturing the beauty and elegance of horses seems like an escapist task, but for Deventer, it is a dive into the origins of social violence and looking into structures of abuse.

Her project about sex workers led her from Brussels, Athens and Paris all the way to Ghana, where some of the women she photographed and interviewed were from. She wanted to better understand the culture, social conditions and economic hardship that led many young women to work within the sex industry in some of Europe's capitals.

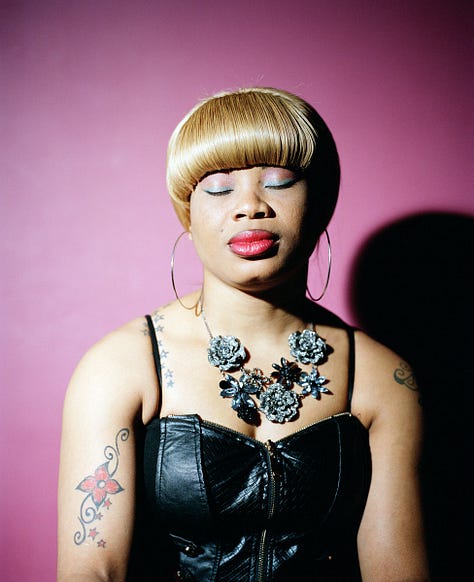

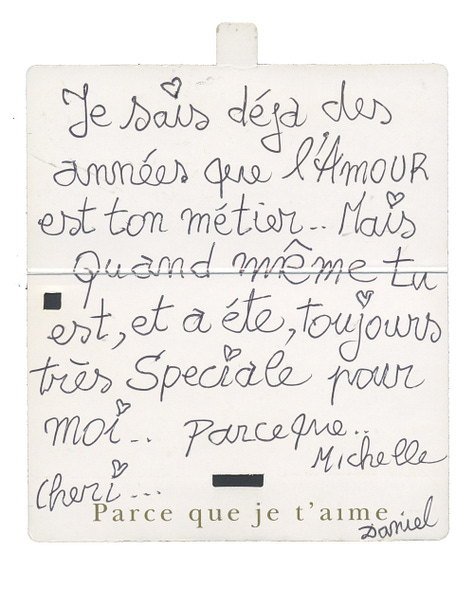

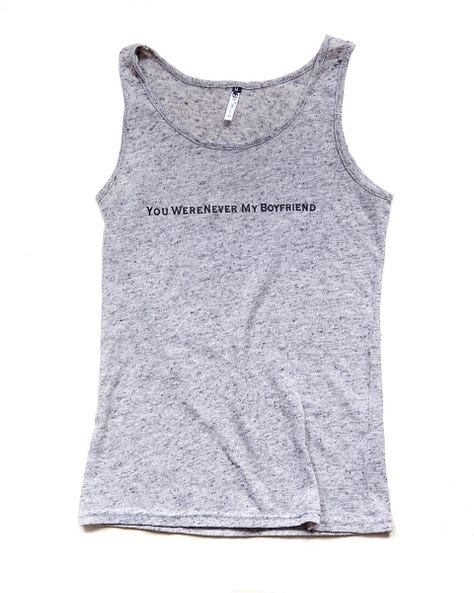

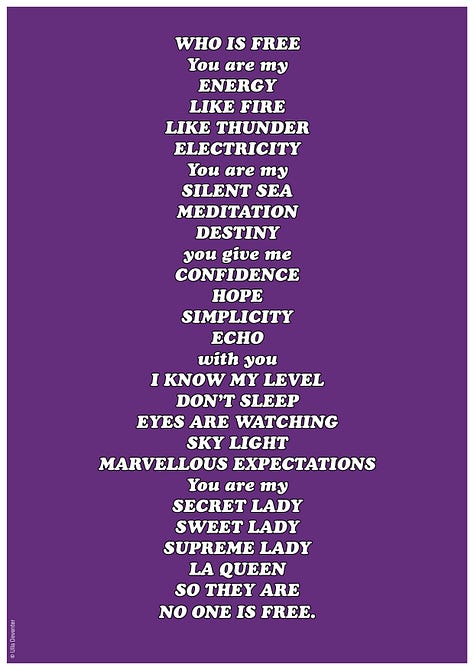

Her series Butterflies are a Sign of a Good Thing is not a documentary work but an elaborate combination of staged portraits, still-life images, written notes, drawings, and textiles. It explores girls' dreams, hopes, and living conditions, departing from a cliche representation of sex workers. Deventer developed a close friendship with some of her subjects and sees her work as collaborative in its nature.

Ulla Deventer studied at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste Hamburg, the Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts de Lyon and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp. She is a PhD candidate at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, Ghana. The British Journal of Photography selected her as one of its “Ones to Watch.” In 2019, she was selected as one of the five finalists for the ING Unseen Talent Award. Her work has been exhibited internationally and supported by several scholarships and awards.

What conversations do you hope your work will spark?

My work is driven by personal emotions that I can share with the individuals I portray. They inspire me to share their stories, and my language is visual, although I sometimes incorporate quotes from conversations or literature.

My work acts as a valve to cope with the pain I sense in those individuals, to a global, universal pain in the sense that we are all struggling with our own issues. After several years of collaborating with various women on this subject, I now portray horses. They allow me to become more intimate than with women because I can show their eyes and their identity. The violence they face is very similar to social violence, which enables me to look at structures of abuse from a more complex perspective.

I pose questions: Why is society soaked with abuse, but few people speak up about it? Why are humans more obsessed with their egos and positions of power than with love and care? Sharing these stories in my installations can hopefully leave my audience with very personal thoughts that last and grow, eventually opening up broader conversations. We all have some of these stories inside us. Sharing them could be an important first step towards more empathy.

Could you describe your creative process? Tell us about one of your projects.

My creative process is like a constant brainstorming session, combining my thoughts and emotions with what I experience, do, observe, and hear from others. Sometimes, I only notice one thing that seems to capture the essence of what triggers me the most. This might be the start of new work.

I work very intuitively, by feel. I seldom use sketchbooks or create storyboards. I rather take notes or recordings. My notes and some key works and objects around me inspire me to think, touch, or adjust them. Related theories are important, too; I especially enjoy listening to podcasts. The visual grows mainly in my mind and details emerge while making the work. Most of the time, I think something has the potential to develop into a powerful piece right from the start. It won't speak to others if it does not speak to me. I am very radical in my editing. I am, therefore, also very slow in my process.

In some of my recent works, I portray traumatized horses in photographs and, more often, slow videos, which gives them more presence with their body language and gaze. I can create these works because I have known the horse community for years and go to their activities. I am often at the race track or visit their training and their stables, they know me as a rider as well. And through my horse rescue activities with The Six Freedoms, a network I founded some years ago.

It is important to be close to the community I work with and to get to know the life stories of individuals to create something meaningful. This takes time. But this way I collect my archive, as memory, recorded, or as physical works.

My strongest installations have been site-specific and only lasted for one event. Sometimes, I enter a space that calls for one of my works. As a start, I then select and edit a video and sometimes sound and add other elements, like objects and ready-made, domestic fabrics, to complement it. The light condition is very important in the installation space as in my video or photographic work. I need to be in control of it and prefer showing my work in the dark. It gives more focus and links to the night, which is universal and connects us all globally. In the dark, there is no feel for time and space. We all long for intimacy. But it is in the dark or secret when abuse happens so easily.

For practical reasons, I work on a low budget and with low tech. I like things to be simple and easy to move. It has to feel accessible, not like something untouchable, because of its high value.

I have also created performances with jockeys Alex Uwuso and Issaka Garriba, police horses Naa Gbewa and Olala, trained by Eva Ippendorf in natural horsemanship, together with dancers President Dangote, and the sounds of the jockeys and horses’ heartbeats, which I collaborated on with sound artist Leon Eckard.

Detail of the multi-media video installation "Passion can be Destroyed" at Villa Monta in Kumasi, Ghana, April 2023

These are projects I seek to develop further, and I most recently worked on a dinner performance for horses and humans in collaboration with Zoë Binetti, aka zozoTransistor and experts from The Six Freedoms. The idea is very simple, and I have had it in my mind for a long time: setting up a dining table in the middle of the green, with a white tablecloth decorated with food that can be enjoyed by both species. We made a first try-out that went beyond my expectations. The horses behaved amazingly and the experience of all eating from one table was truly intense and beautiful. Here, too, the dining table is linked to personal, quite violent memories of the domestic and my childhood, which I try to transfer here into an alternative idea of a family, of togetherness by choice, bonded with love.

How does your studio or workspace (physical or mental) look like?

I create in the streets; every place can become my studio. For many years, my studio was either a personal place or the red-light district because I collaborated with female sex workers over many years. Now, my process takes place in my personal daily life, which I share with horses and the horse community. To stay creative, I must balance the mental and physical. Physical activity is very important for me; I must stay active to create. Good ideas often come during my runs or while spending time with my horse. Simply moving between scholarly and quiet basic spaces allows me to see and apply the connections.

My home then becomes partly my studio, where I can collect and edit work and be surrounded by it. My home, too, is flexible. I move between different places, which is sometimes exhausting but also allows a certain flow. Each space has a different energy.

Is your art influenced by where you were born or live now?

Yes, definitely! This is very interesting because it becomes increasingly obvious how my childhood inspired how I live and work today. I grew up in Northern Germany, in Quickborn-Heide, on the outskirts of Hamburg. Our house borders the forest, and I was born during an extremely hot summer. My parents let me be naked most of the time, lying in the grass in the garden and gave me fresh seasonal fruits and food to eat. We kids spent most of our time outdoors and created our own spaces in the forest, the garden, or the streets. My mother ensured we had good materials to experiment with for handcrafts, paintings, or drawings. My father gave me his camera one day, and I became obsessed with directing short documentaries with my friends and taking portraits of my cats, horses, and close friends. I even invented a horse monopoly and made a receipt book for humans and horses at the age of ten. Horses have always been a source of happiness and safety for me; they heal and guide me.

All this sounds like a perfect childhood. But my parents divorced during my brothers and my teenage years, so we had to grow up apart. This period was filled with very tense and mentally violent moments, which definitely left many marks, including how I sense mental violence and abuse easily. It might be a reason I feel close to horses, too: as flight animals, they survive on their high instinct for safety and threat. Humans with experiences of trauma can relate to this and bond instinctively with horses.

Today, I feel very much at home and connected in Ghana. I enjoy the heat, the colours of the tropics, the peaceful mentality, and the life that happens outdoors. I need this intimate connection to nature, sensing it as I wake up, hearing its beautiful sounds, the diversity of light, and the weather conditions. My horse now lives next door, something I could only dream of. Having horses and horse experts living with me is obviously deeply inspiring.

Who are some of your most important female (womxn) sources of inspiration and influence?

One is my grandmother, Ulla Deventer, whose name I bear. She died in a car accident with her husband at the age of 29 while on the way to take her artwork to the market. She was a ceramist, and her studio was open to everyone, she was also surrounded by artist friends, and lived a very emancipated life for her time. People tell me we are very similar, not only in appearance but in our character and lifestyles. This connection to her motivates me not only to live a lifestyle that is different from the normative but to work and experiment with materials. Her remains include a few ceramic pieces, some photographs of her, and a life-scale portrait painted by her friend Bernd Funke, which is now in my father’s house where I grew up, and I can sense her strong presence through them.

Then, philosophers like Donna Haraway help me connect my interdisciplinary and interspecies-inspired practice to my thinking processes. She advocates for interspecies connections based on responsibility, such as caring for one another, and explains how we are connected in webs and across species and that we ought to bond in kinship rather than by blood. This refers to other philosophers like Derrida, whom I admire, but Haraway has a scientific background and can apply theory vividly to practice since she also lives close to her dog.

Then works of art friends inspire me, and there are several friends with who I am in regular exchange for feedback. Tracy Naa Koshie Thompson combines science, food, and microbes to create large-scale, colourful installations and images that are moulded by non-human forces. Lisa C Soto creates spaces that connect nature with humans. Godelive Kabena Kasangatis’ performances and installations question the power relations between men and nature, just to name a few. We all are part of the Blaxtarlines community, often produced work close to one another, what makes the exchange more intense. These are just a few of the women who inspire me.

What personally or professionally excites, worries, or keeps you connected?

There is a lot that worries me about our political, globally difficult situation, genocide, and wars. Many close friends are also facing challenging living circumstances, in addition to the omnipresent domestic violence that I occasionally witness next door and must personally act in, as well as the cases of horse emergencies we operate and the general abuse of horses and animals.

My lifestyle keeps me grounded. It provides me with beauty and hope because it relates to the people and animals I love and care about, who only give me positive energy. I am excited to develop new works; it makes me happy and keeps me going.

For further information about Ulla Deventer, please visit her website and Insta pages, but first, spend the next week with Ulla by following her takeover of our Instagram page!