The frustration of not being able to paint a tree with all its leaves was the first impulse to try photography. Today, the Swedish artist and teacher Eva-Teréz rarely captures the reality of this momentum. On the contrary, she deconstructs it.

Cropping, editing, eliminating, and using automated processes is Eva’s artistic expression, which she uses to talk about the climate crisis, sustainability, consumerism and the damaging habits of society.

It’s fascinating how these edited or discovered pieces of photographs in her works merge into one aesthetic talking image. While photography is a medium of capturing a moment, in her case, it takes on a completely different meaning.

Together with the artist, we go deeper into her creative process and the meanings of her works.

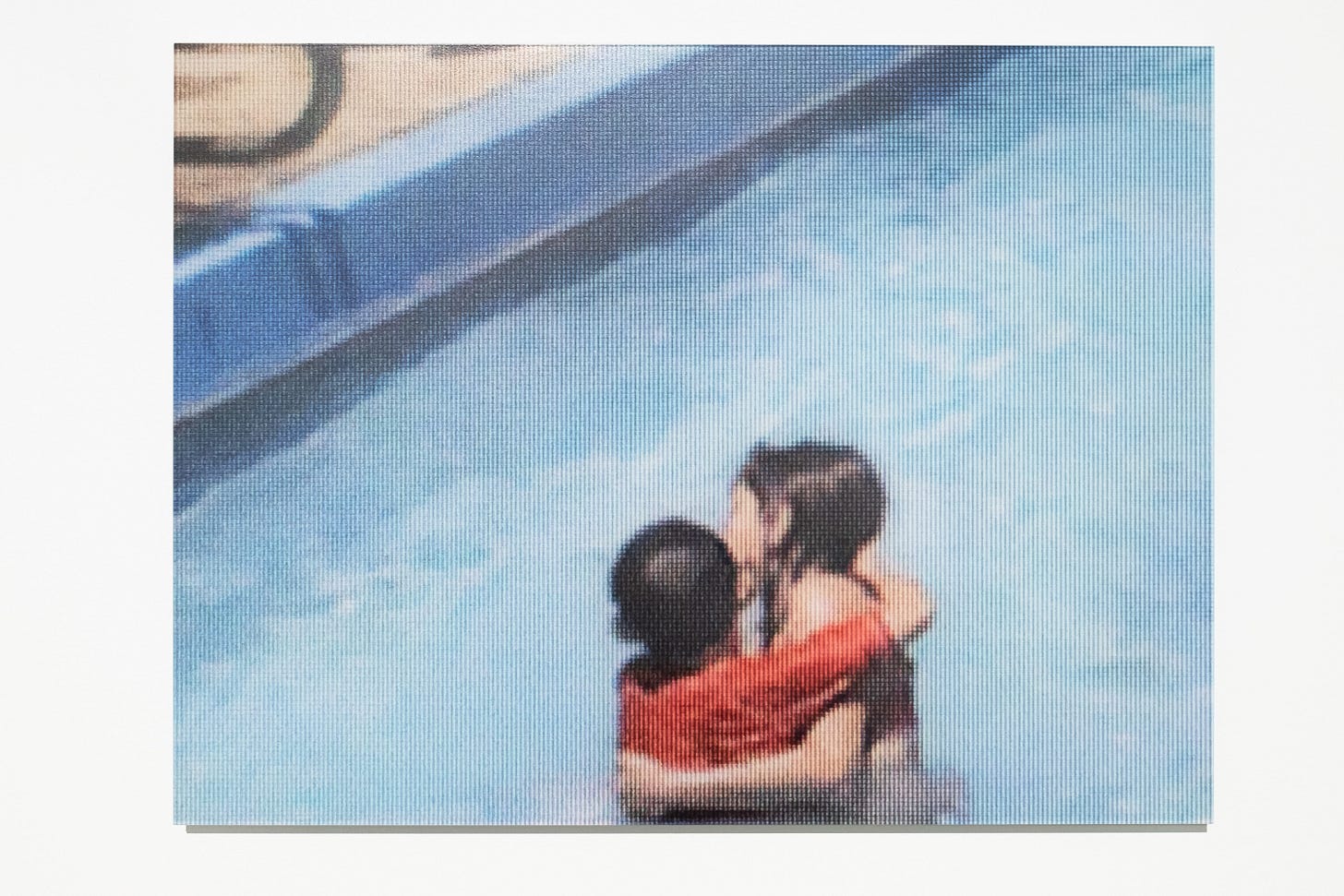

Tarantula: Authors And Arts: The exhibition “In the Absence of Shadow” that you presented at ‘Galleri Duerr’ in Stockholm, was the first time I saw your works. My eyes were drawn to the grey pictures against the white wall. I saw the silhouettes of children swimming in the pool. They were fading, shadowed, as something bad was about to happen. Was my intuition right? Was that what you wanted people to feel by watching the photos?

Eva-Teréz: I believe that art should be possible to interpret in various ways and what I can hope for is that my images will evoke some feelings in the spectator. The images you mention as “grey” are a result of a method where I have created monochrome images based on the motifs’ colors and their saturation, instead of reflected light which usually defines the photographic image. The images depict children on what is called a “lazy river”, a manmade flood with a continuous flow of water where you can float in a never-ceasing loop. For me – a perfect incarnation of non-action.

Consumerism, the climate crisis, sustainability - these are the themes that you address in your work. You choose issues that are problematic for society. Tell us more about the projects you have created, how their ideas came about and what you wanted to say with them.

I am interested in how humans act together as a society or how we, myself included, do not seem to act at all. We live as if we are not aware of the unsustainability of our habits. Using contemporary visual imagery, I try to understand how these habits of ours might impact our future. Through various techniques, which in different ways reduce the amount of details in the final images, I wish for the viewer to see the images for what they are – depictions, not so-called reality, which is otherwise often associated with the photographic medium.

What do you think is the purpose of art in general? And how much impact do you think art can have on its receivers?

I do not think that there is, or should be, just one purpose. The impact one artwork will have varies greatly from one viewer to another. As with all information, it is not just what our eyes see, as what prior knowledge and understanding we have of what we look at, that will affect the “impact.”

In your artwork, we see many different uses of photography that the ordinary eye doesn't recognise or know. Like using photogrammetry through Google Maps 3D and Street View. What was the first reason you started working with them to express your ideas?

I began using found photography and text in combination with my own photographs around 2015 whilst working on an artist book; Without Interrupting Your Life. It enabled me to portray the topic I was working with and since then I have continued to make use of found imagery for my works.

Your process seems to take a long period from the beginning to the final image. Tell us about the process of how the idea becomes a form?

Often the most time-consuming phase is to collect the imagery. For example, to portray people with their to-go cups in Google Street View, I had to “walk” the streets of many cities as it wasn’t possible to search for “person with to-go cup” since the imagery in Street View is not indexed in that way. For my works, I most often search for and collect hundreds or thousands of images, from which I later make a quite narrow selection. For a lot of my works, the most important step is the cropping of the image. It is as much about what is shown in the picture as what I choose to leave out. Or most often – even more about what is left out than what is visible. Not only what is left out by cropping but also details that are lost, or obscured, by digital artifacts or insufficient resolution, caused by an automated process in the creation of the image, or by later editing.

In your work ‘Holy Grail’, you use Google Street View images and walk the virtual streets, observing people and the culture of coffee to-go, to create the feeling that you were actually there. For other works you have been using Google Maps 3D to search for places like airports, theme parks and shopping malls. It's like you were traveling around the world while still sitting by the computer in one place. Is it like surveying the world and drawing conclusions?

Yes, as mentioned, for Holy Grail I went for virtual walks to find the people I wanted to portray. For two other series, I’ve been able to first do some research to know where to “travel” on Google Maps. It was not my intention to survey or draw any sociological conclusions, but it has been an inevitable part of some works. For example, for Holy Grail, I walked around Dallas, and compared to New York, the city was virtually empty of people; no to-go cups to be seen. Also, in other cities in the south of the USA, there were fewer people out in the streets. I assumed it is because people in these cities more often travel by car and prefer to drink their coffee whilst driving or in other air-conditioned spaces.

In one of your interviews I read that your artistic works are usually based on digital errors. I related to this sentence. After working at a photo studio myself for a few years, I started getting bored of beautiful images people would enjoy, so I started to be interested in the mistakes or errors that I have made. What do the errors in your works mean?

For me, the errors both act as a reminder of the image being “just” an image, and not reality, but they also add a materiality of sorts. When working on digital files in their immaterial state, the pixelation, artifacts, or other digital qualities, lends dimension and tactility to the image which I try to retain and enhance, through the choices of printing methods and physical materials for the final works.

Do you take simple photographs, like capturing moments of your life, your family and friends, celebrations? What do you think of these kinds of photographs as a visual artist who uses photography in very different ways?

Unfortunately, I do not photograph friends and family that often. If I were to look at the images snapped with my mobile phone camera, I would probably find more pictures of nature than of people. During the pandemic though, I snapped some portraits of people at zoom – it was very much in line with my artistic working methods, capturing images through making screenshots and with a nice, low image quality at that!

What was the reason you chose photography as a medium for expression?

As a 12-year-old, I was very dissatisfied with not being able to draw perfectly, e.g., a tree with every leaf included. At 15, I spent all the money earned at my first vacation job to buy a camera and two lenses and started to learn how to photograph, develop film, and make prints in the darkroom. Now that I could capture every detail of the trees, I realized that accurate details were not what I wanted either. I liked experimenting in the darkroom but had no ambition at all to become an artist or a photographer. It was not until several years later when I discovered Photoshop and the digital camera, that I got interested in working professionally with photographic images.

We live in a world full of images, what do you think is the future of photography?

If you had asked me five years ago, I would never have thought that today we would have online AI apps, generating photographic images. I don’t think I can make a good guess of what the future will hold in terms of new technological development. Hopefully (and sadly enough), we might have learnt not to interpret photographic images as being closer linked to reality than other types of images.

Can you share with us your next creative plans and what are you currently most interested in as a visual artist?

Through the years I have learnt that my creative plans always end up somewhere else than what I imagined when I started. Therefore, I cannot share recently started projects right now. I have even stopped applying for grants where I need to describe what I am going to achieve months later. But I continue to work with and dig deeper into the specificities of digital materiality – exploring new ways of translating the immaterial files into a physical state.

To learn more about Eva-Teréz’ works, you can follow her on her Instagram account.