Something Funny Happened On The Way To The Supermarket Art Fair

Some stories just never leave you alone

If you are a regular or have just landed on Tarantula: Authors and Art, welcome. As our house team of writers joins you on this adventure this year, we hope that the stories we tell as well as the artists we feature will inspire you to start your own creative journeys. If you enjoyed Maja's tale, please leave us a comment, share it with your friends, or subscribe

.

On the third day of the art fair, which took place in Stockholm, I was getting ready for my afternoon shift, when I found myself crying at the bottom of my extremely white bathtub. After greeting and meeting hundreds of people since May 10th when Supermarket opened, I found a moment for release.

The few months leading up to the fair were intense yet guided by a dream. It was the first time we were going to introduce our magazine to the real world, to artists and art connoisseurs in person rather than just digitally. Our first print magazine was being designed and written, artists that we featured were contacted, texts edited, there was a lot of correspondence and a few sleepless nights. It was a wonderful but at the same time exhausting experience, as most independent projects are. But being part of this creative process is what makes life worth living.

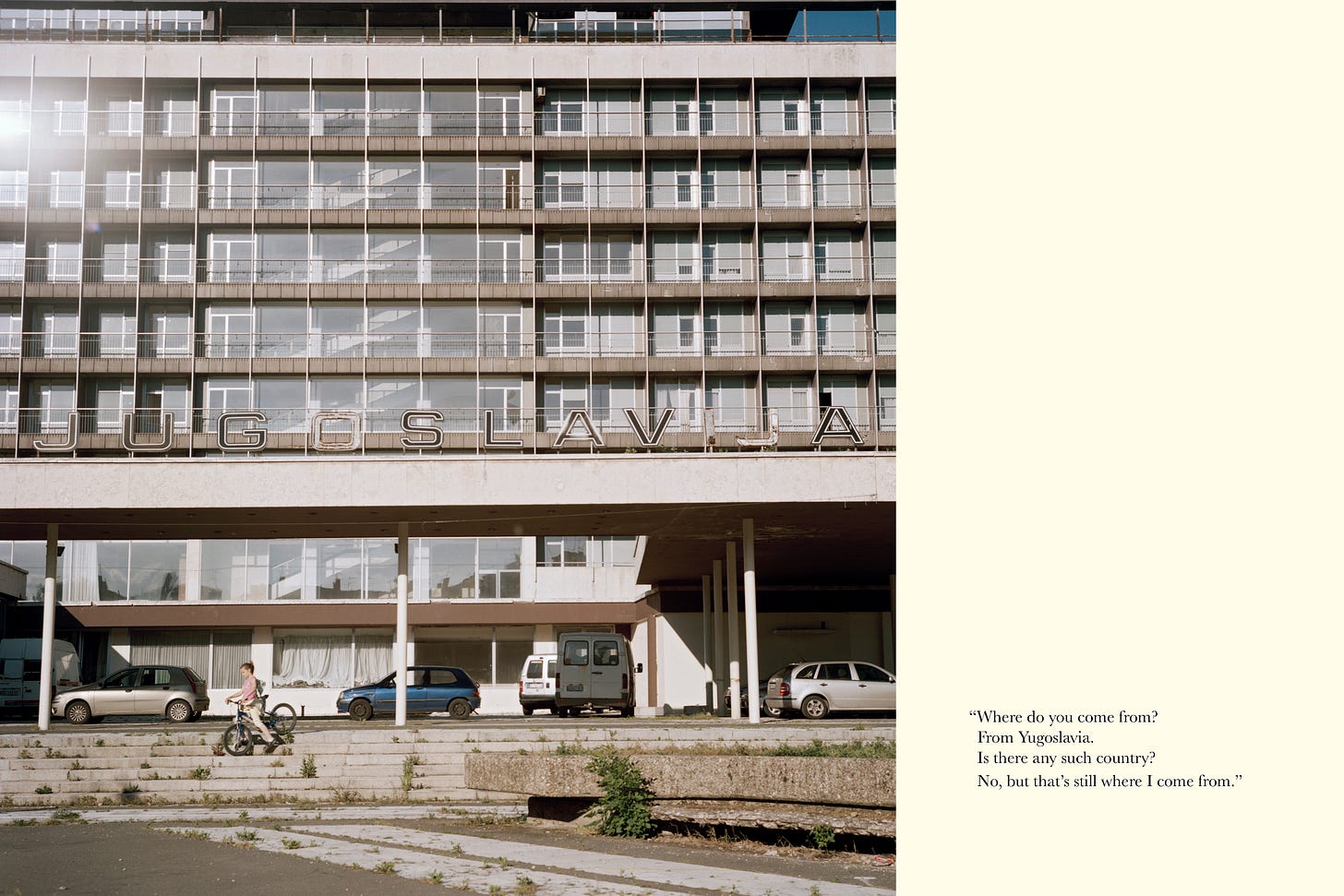

The cover of our first print issue was graced by Polaroids of female nudes, women who directed themselves in front of Dragana Jurisic’s camera. Their tastes, traumas, pleasures as well as wounds all vividly displayed. Dragana Jurisic is a Dublin based, Irish photographer. Her name, on the other hand, is not Irish, just as mine is not Australian, Swedish, or American, where I spent the majority of my life. Her name, like mine, reflects our origins: we were both born in Yugoslavia. A name that produces so much anger in many, but it is a place where I had a Pippi Longstocking-like utopian existence in my youth, a life for which I never stopped longing.

I was startled as I read Jurisic's interview with Sandra Vitaljic, another Stockholm-based photographer who was also born in the same "ghost country," for lack of a better term. I’ve never met an artist who so accurately captured my entire life. My thoughts, feelings, as well as my sense of belonging to an invisible order.

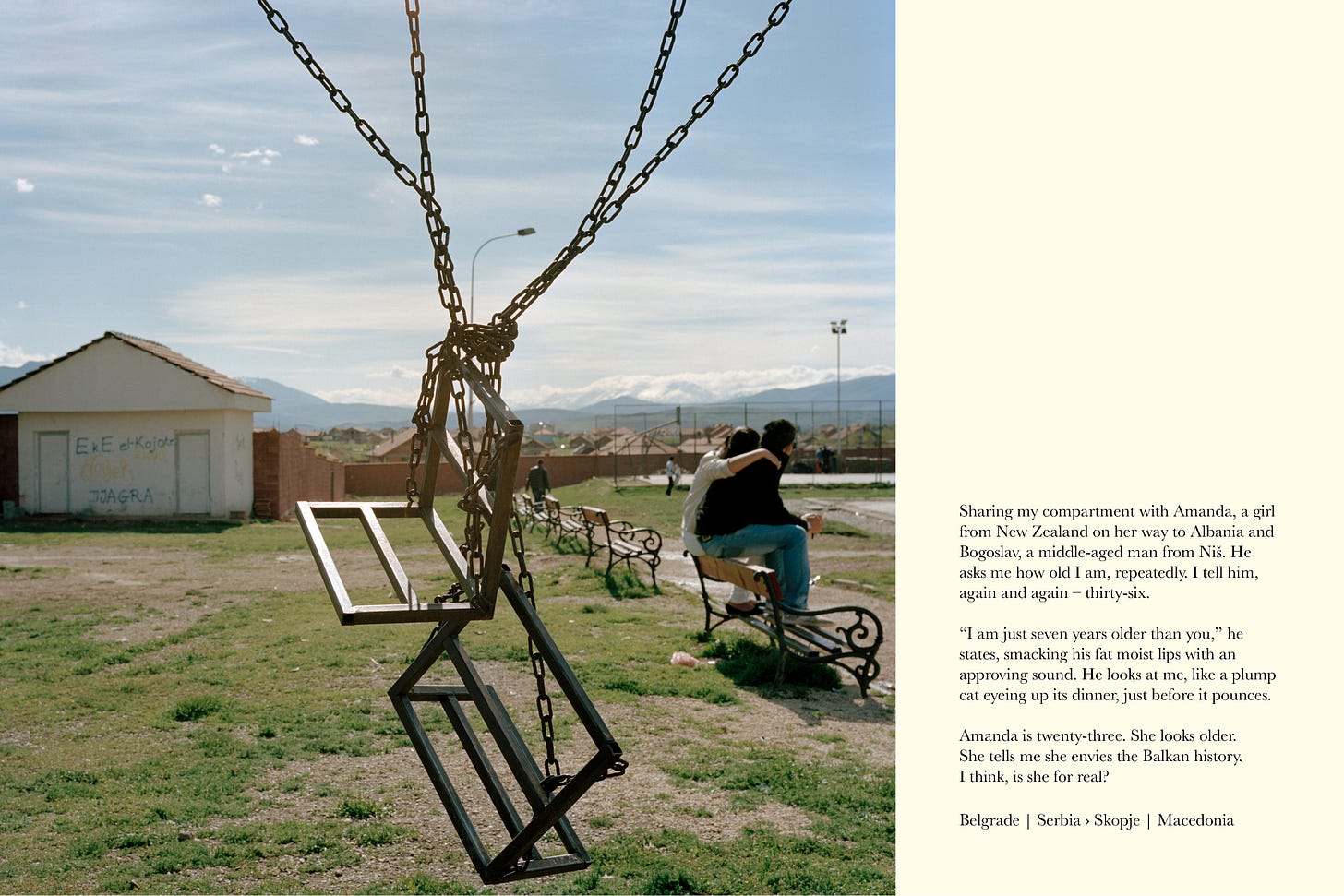

Jurisic’s journey took her across former Yugoslavia “in attempt to re-live my experience of Yugoslavia and to re-examine the conflicting emotions and memories of the country that was” as she explains on her website. As I read that, I realized that it was exactly what I tried to do shortly after 9/11, which I experienced from my apartment in New York City. For many years, New York was a complicated but safe haven for my mixed, Serbo-Croatian family from the war, but when the twin towers fell,, a strong urge brought me back to a post-war Balkans. And just as I remember exactly the events of the morning when life in New York changed in an instant, I also remember the morning when the war in Yugoslavia drove me into a new destiny. The morning I started to question what is identity, what are nations and religions? How can a country just disappear? Nothing in my life has felt permanent afterwards and yet change is something I still fear.

The war in Yugoslavia broke out while I was living in another apartment in New York. I was maybe 17, my best friend Nina, a German girl, had slept over the night before. We were one month into the fall semester after a long summer. That summer I returned to Yugoslavia to visit family and friends. One day, that same friend called me from Germany to warn me not to travel from Serbia to Croatia, that a war had started. I had no idea what she was talking about. ’There is a conflict but everything is about to end very soon,’ so I thought. Together with my mom, I flew from Belgrade to Zagreb with what I later realized was the last plane for a while between the two capitals. And we took a bus back from Zagreb to Belgrade, going down the same highway that we had traveled on countless occasions to see my grandparents, aunt and uncle. We drove by gorgeous sunflowers facing the sun, and hay fields with circular bales of straw coiled up; fields that separated us from nameless villages and cities, one which would soon become quite famous, Vukovar. Images coming from that town on our TV screens left us astounded, but it took some time for everything to sink in. It was nearly impossible to reason with what was happening. Until that morning.

Nina and I woke up to get ready for school, and while she was in the bathroom, I entered my living room where my mother was frantically running left and right. She was shaking as well as getting ready for work when she told me in a rush that our grandparents’ apartment was hit by a missile. I remember when I told my grandmother that my first best friend in New York was German, she felt a bit uneasy as I was raised not to hate anyone, but it was ok to hate Germans whom she fought during WWII. But who was I allowed to hate now? Who did I belong to now, Serbia or Croatia, these subgroups whose traditions or ways I knew nothing about? Their hatred for one another shocked me because I had traveled freely and lovingly along the same highway my entire life, ignorant that it would one day be divided into two nations.

That morning in New York, I became a mute. Four years of college passed by without making many friends or being vocal. Maybe it’s not a coincidence that during that period I found writing, specifically playwrighting. My first longer play was about two brothers waging a war over their pizza restaurant. I gave them words that I could not say on my own.

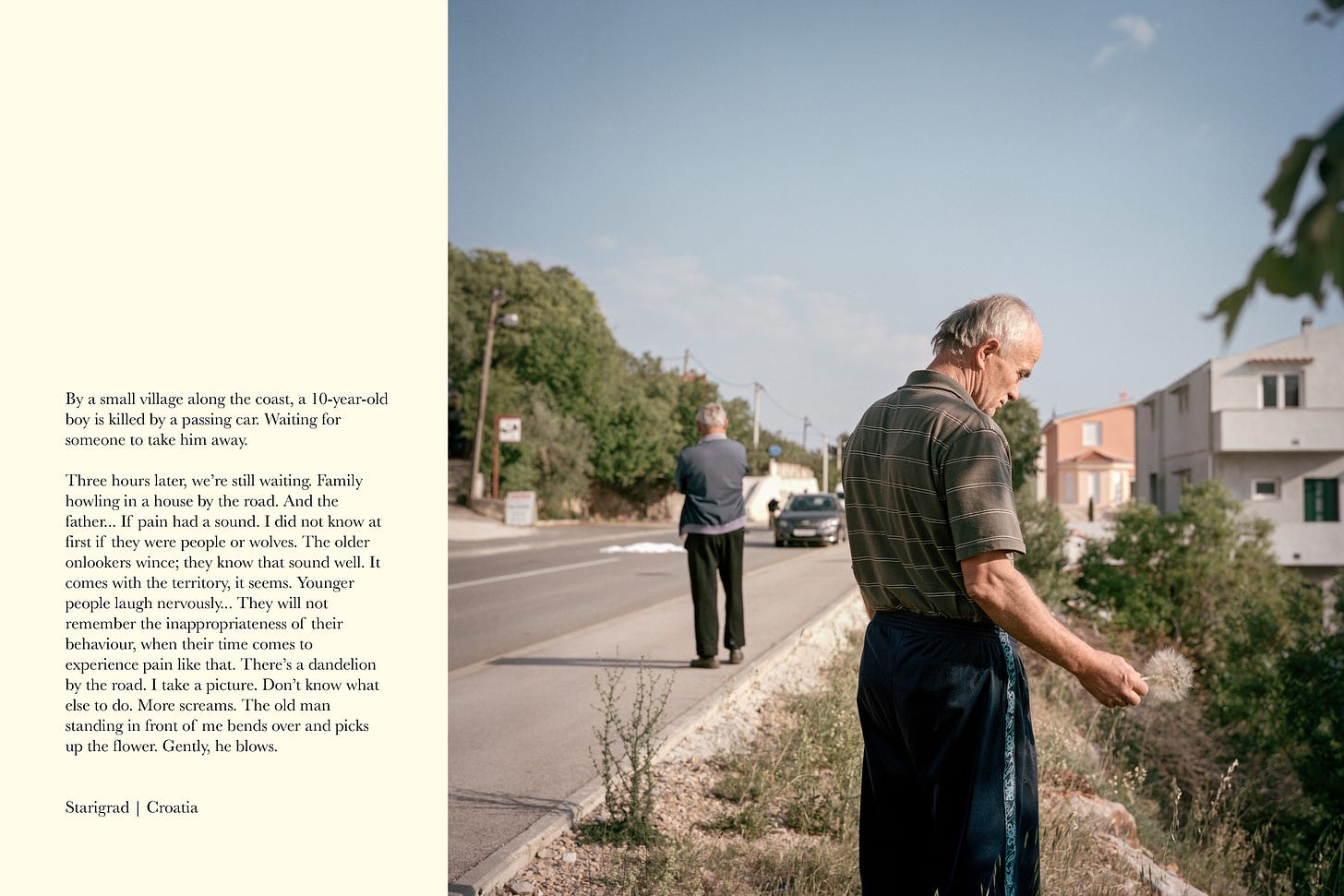

Dragana Jurisic’s photographs and texts opened a wound from 30 years ago along with what happened on the second day of the Supermarket Art Fair. A young 21 year old Ukranian woman living up in a refugee camp in the north of Sweden protested on the entry floor of the fair as one of the exhibits showed Belorussian artists, all women who revolted against their dictatorial government and whose lives were at risk. After many attempts to present the gallery’s point of view, she left the art fair angry at the organizers, galleries, Sweden. It was an uncomfortable moment for everyone involved, and especially for the good natured and open minded Swedish organizers who were trying to support everyone. Times are sensitive, and as most of us think of the war as something over there, it’s closer than we think. It hijacked the everyday lives of many.

When a friend of a friend of a friend from another gallery at the fair came down to say hello and check out our booth, even he jumped to conclusion when he saw that the first article mentions Yugoslavia. “Oh this is some Balkan magazine,” he said matter of factly with a slight condemning voice. I justified the magazine that we are a mixed group of expats, which we are, who met in Stockholm. But his tone stayed with me, some would just brush it off. I know that I am also extra sensitive as are many others who have lost their roots but continue to coexist in the world carrying the burden of their birth countries.

Feeling vulnerable myself, I looked at the twenty one year old Ukrainian, and empathized with her and what she was going through. I remember being 17, becoming an insomniac, imagining how one could kill the then-president of Serbia, Milosevic who was clearly to blame for sending troops into the rest of the country.

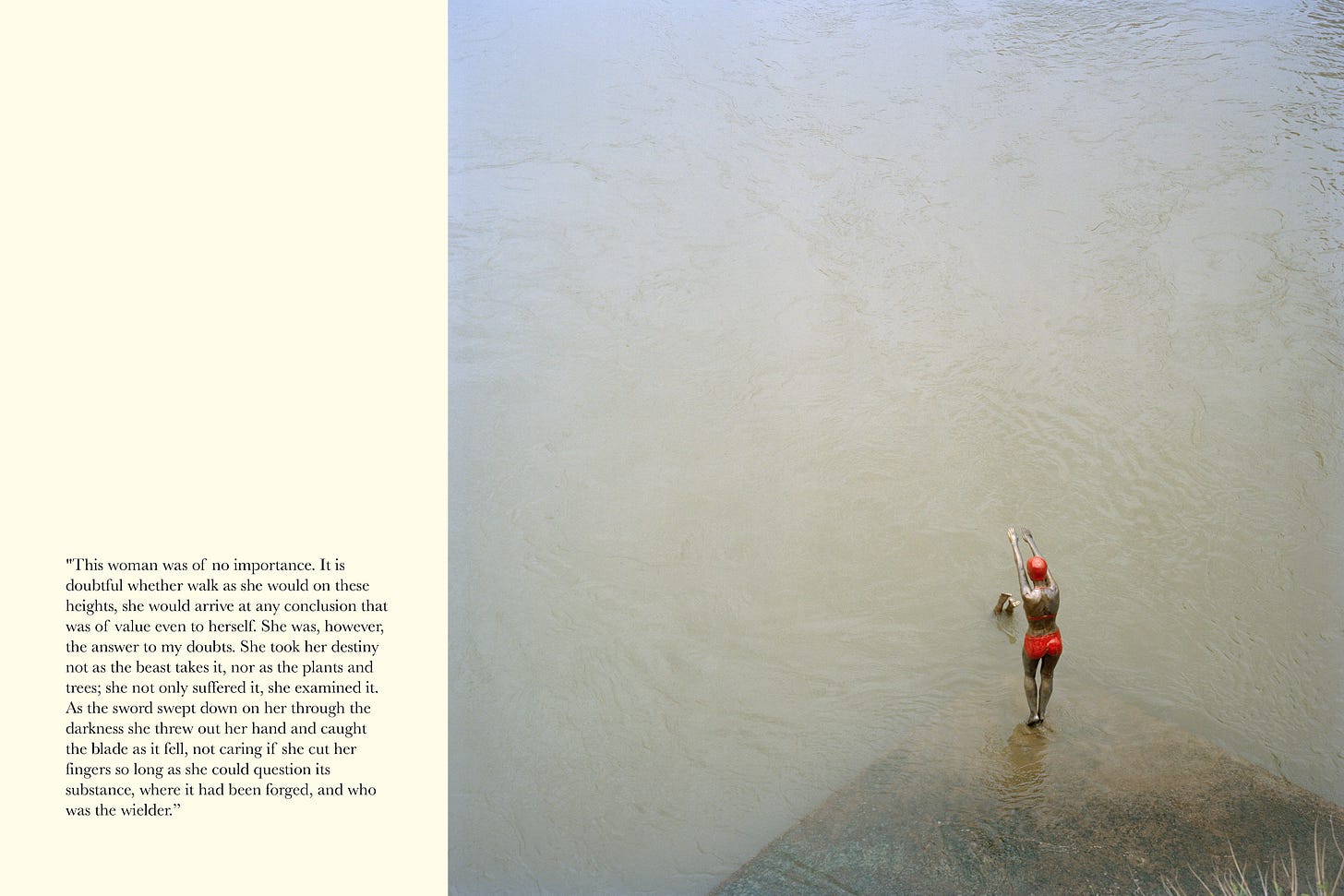

I looked at the young woman and thought one day, when the war is done, she will return to her homeland to look for what she left behind, but for a while she might have a hard time finding it. And maybe she never will. A birth and re-birth of a nation can be quite brutal, leaving many people without a compass.

After 9/11, I was determined to find my way back home. I packed my bags, said goodbye to my immigrant parents and spent three years on the road between relatives and work in Croatia, friends in Serbia and in pursuit of a broken love in Macedonia by trying to fall in love again with the wrong man. It was messy, yet I felt very alive. I was blamed for what the other side did in the war because I belonged to them as well, and celebrated because my mother gave birth to me, therefore I presumably belonged more to the side from which my mother came. I felt adored and accepted while living in the area that was not involved in the conflict, and how I wished to stay in love and be there. But their borders felt suddenly too small, and soon after I left, nationalism crept across that area, manifesting itself in kitschy art and slogans.

I smoked many packs of cigarettes during that time, which I never did before or after, but it was a very Balkan thing to do. I went to a lot of raves and parties and drank a whole lot and ate beautiful local food. Working on films during that period, I also visited notorious prisons, encountered the remnants of the Ottoman Empire in the highlands of Macedonia, and visited islands that were once off-limits to the public. I was fired from a job for writing few of the words from one side into the TV scripts of the other side even though the difference in language is 0,00000000000001 %. (Maybe even more zeros involved) Twenty years later, scriptwriters from both sides freely cross the border to create TV series together.

For a long time, I disregarded my own scars and tried to find compassion for all of them even though none of them gave any attention to my hurts. I was always to blame for something. I was in their country, I didn’t have one of my own anymore, even though my roots were buried deep under that land. I have put myself through all of this in hope to find what I’d lost, but hadn’t found much that connected me to a sense of home. I felt alone in a room full of people who had learned the same language I had when I was born. So I left when love came unexpectedly from the North. It was time to let go.

And after another stint in New York, I found myself in Stockholm. Despite arriving with a loving family of my own, again I felt alone, trying to build a home in a culture nothing like any of my cultures before. No matter how liberal and open they appear to be, they protect their own. Maybe I just lost faith in countries or big groups of people anymore. Thus, on that third day, on my way to the Supermarket Art Fair, the wound burst open. But after the cry, I put on my clothes and went back to the fair where I met so many interesting artists who wanted to share their stories, I presented our magazine that was created by international artists and writers, and just for a second, despite carrying the story that will never leave me alone, I felt calm and sensed that I belong.

Come back next week to read about some of the artists that we met at the Supermarket Art Fair!

❤️❤️❤️

Thank you, Maja