Stitching Stories

A conversation with Tarantula: Authors And Art's Inspiration for June , Gözde Ju

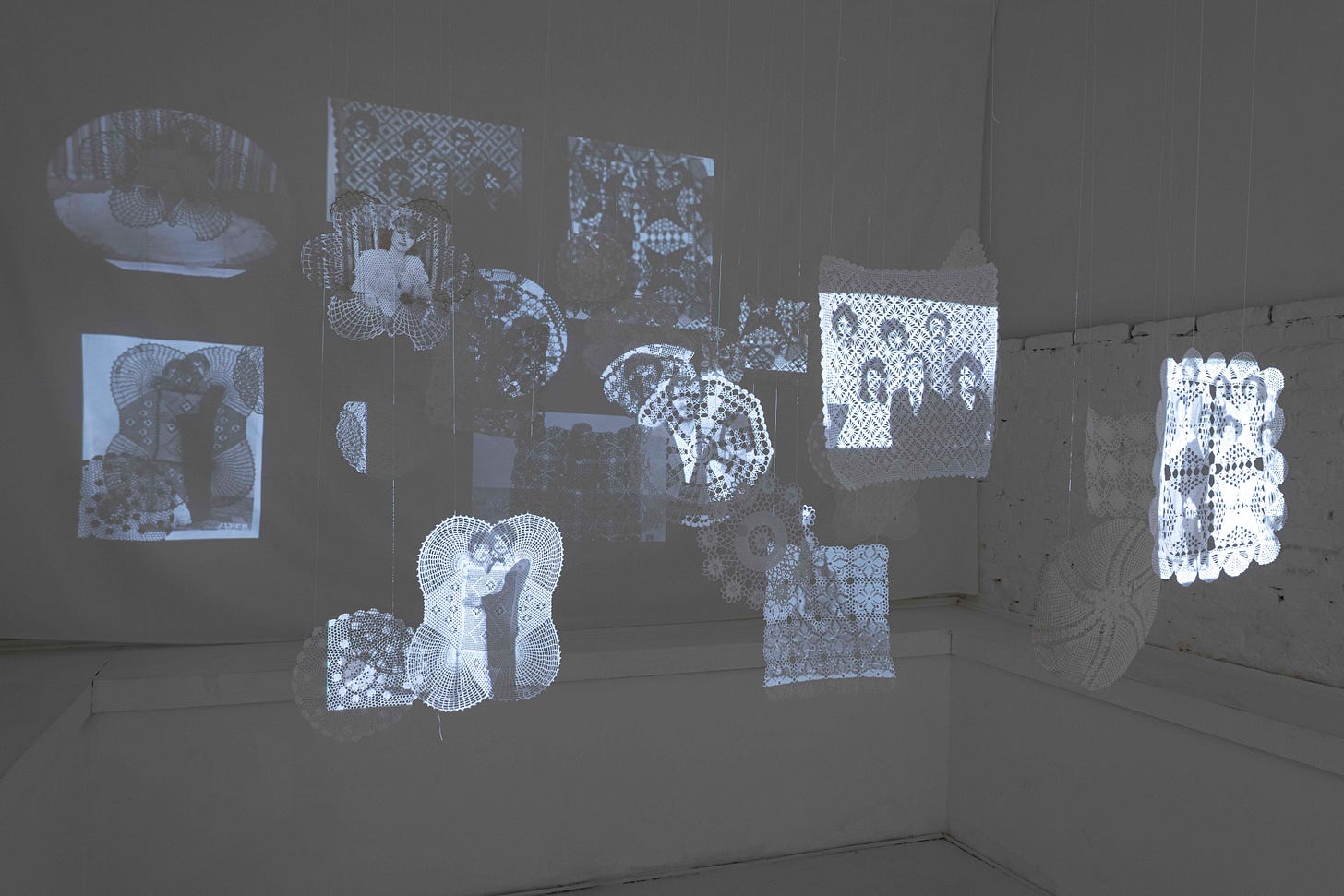

To be in a room where experiences are portrayed by handmade stitching that is so delicate and fragile, and full of history that the craft itself holds, one can't help but wonder what secrets are hidden behind the hundreds of intertwined lines. The black thread patterns, which feature small details such as a jug or a table, a painting within the stitched image, spread across the walls like the most intricrate spiderweb catching the viewer’s attention and instantly captivating them. Embrodiery, lace, stitching, which are commonly associated with women's decorative art forms, are transformed in Gözde Ju’s oevres into tales of immigration, belonging, and, of course, the role of the feminine in today's society.

When I walked into the space of the Frankfurt on Main based collective EULENGASSE at Supermarket Art Fair, Gözde Ju’s artworks immediately took my breath away. I could imagine that after long hours of stiching, surrounded by the whirring sound of the sewing machine, the threads, as Ju explains in her interview with Tarantula: Authors And Art, become one with women’s bodies. The handiwork has already been deeply ingrained in us through inheritance and trousseaus from our mothers, grandmothers, our maternal blood line. And, while lace, needlework, and doiles have traditionally symbolized purity and new beginnings, we also understand that they carry memories of patriarchy, dominion and domesticity. Yet, Ju infuses fresh life into a craft that may be on the verge of extinction, by giving threads a new meaning, and by using them to reflect on her place of origin, Turkey, and bridge with the new world she finds herself in, Germany.

Maja Milanovic: Tarantula: Authors and Art’s name is derived from the spider tarantula. Tarantulas symbolize connection and community. Your artwork reminds of the work of a spider. Do you choose your art form, or does it choose you?

Gözde Ju: First of all, I would like to thank you for your interview invitation.

I can say that in the beginning, my art form chose me, but later on, we continued to choose each other. In fact, I studied printmaking and painting as a double major at university, but the experimental nature of traditional printing techniques and the journey of surpassing their own plane have always been interesting to me. I was always in search of new directions that included the material itself. In this search for materials, threads played an important role. During my master's, I worked with threads on the serigraphs I printed on canvases. These were my first attempts at sewing and textiles. However, my first true engagement with threads and textiles resurfaced when I moved from Turkey to Germany.

For the first three months, I didn't have my own studio, so I used my living room as a studio. Two days after I moved, Germany went into a very strict lockdown due to the pandemic. I could only carry a limited amount of materials from Turkey and had no access to new materials. During this period, I made drawings with the paper and pens I had. While stuck at home, I thought about the concept of home, and eventually, the indispensable sewing box of every home drew me in. Thus, threads returned to the surfaces of my drawings. I began incorporating threads into my pencil drawings. This relationships, as it always does, grew and changed gradually. Thus, a process of mutual development began anew.Recently, instead of drawing my sketches, I began using a needle and thread to create them. In other words, my papers became fabrics, and my pen became a needle.

You draw with a sewing machine. Tell us a bit about the process.

When I think about my childhood, the sound of a sewing machine always accompanies my memories; the sound of my grandmother's sewing machine, echoing through the entire house with its "tak tak tak"... My grandmother created wonders on that old black machine. She would repurpose worn-out and discarded clothes, turning them into large bedsheets and pillows. As a child, I would look at that bed sheet and try to figure out which fabric pieces belonged to my grandfather's clothes and which ones belonged to my grandmother. The machine's sound and fabrics hold a special place in my mind, so it's no surprise that they've found their way into my artistic practice. Now, this sound continues to exist in my own studio, creating different stories.

In your art, tradition and modernity meet. What can stiches from the past teach us about the present?

Lace and many unique handmade objects from the past, as well as the women in my family, hold great value for me. I find it important to carry these items into the present because they are objects that contain cultural codes and memories. However, today these cultural treasures are in danger of disappearing; very few women now produce such handiwork, and my mother was the last generation in our family to continue this tradition. When I was young, I tried to learn with great enthusiasm, but I couldn't dedicate enough time due to my busy school life. Almost no one from my generation creates these handcrafts anymore. Another important point is that these handmade objects have always been invisible in a patriarchal society. The objects that women produced to beautify the home and create a sense of family connectivity were often seen as mere pastimes for women. However, I view these crafts from a different perspective. Lace and handcrafts carry the story and memory of the past to me, and I add them to today's memory without altering their essence. I combine this memory from the past with my own memory.

Are you choosing embroidery or sewing to carry on the ancient tradition of ladies in your family? When others attempt to stray from customs, you embrace it and use it to further feminism.

With the unveiling of the lace, tablecloths, and pillowcases, my mother made for my trousseau, my art also transitioned to a different dimension. I took a long, hard look at these meticulously crafted objects, hung them on the walls of my studio, lived with them, and finally gained the courage to create something with them. I embrace these traditions not so much to continue them but because they represent the stories of women, particularly my own. Additionally, I believe that lace and embroidery, as political objects and actions, present a fragile and delicate form in contrast to the violently structured patriarchal society. Photographs of the lace and fabrics reveal the cultural memory of the social geography.

While narrating the shared stories of my family's women or other families, I critique migration, gender, and domination. Beyond serving as common language among women, the lace and handmade items meticulously crafted to beautify the home become political objects, intertwined with the invisible domestic labor of women. I question family relationships, the contradictions within the home, gender roles, the act of creating a home, and where women fit into all this.I try to look at the memories passed down through generations. I can say that the experiences of other women and my own experiences are intertwined, stitch by stitch.

The themes of your work often follow your personal history from growing up in Turkey, whether it is portraying women from your family or images from your days in school. How, if at all, did your creative vocabulary change when you relocated to Frankfurt, Germany?

When creating my artwork, I start with myself. It is true that the society in which I grew up and the one I now live shaped or is shaping many parts of who I am. Since I had the opportunity to view Turkey from a distance, the concepts I've been contemplating have started to appear in different forms in my mind. Consequently, my approach to society and to myself is changing. I notice these changes, some of which I don't like, while others I feel the need to embrace more. I share images, visuals, and thoughts about myself from different perspectives around the world. I observe and reflect on the society in which I grew up, the society I am currently in, and various cultures. Within this kaleidoscopic diversity, I find commonalities, differences, and similarities. Everything I discover takes shape in my consciousness, and this situation is reflected in my artwork.

How does it feel to be an artist who belongs to two very different worlds?

Although there are cultural differences, I don't believe Turkey and Germany are vastly different worlds. However, living between different lands is a wonderful feeling for an artist because stories diversify, and you change along with them. You experience a sense of belonging and detachment to both countries. This gives you the opportunity to view both worlds from a distance. This distance enables you to see many things more clearly and approach them objectively. Therefore, I constantly seek a sense of belonging and feel that I belong to people. I think it's a privilege. I don't belong to just one place.

You also use old photographs. In many of them, you stitch over the men's faces while leaving the women's faces untouched. Can you tell us more about that?

For a long time, I've been collecting photographs from antique shops and flea markets in every country I visit. Along with the notes on the back, I try to follow the traces of these memories. Utilizing photographs belonging to others and my family, I aim to highlight the reality and uncertainty of women's memories, pasts, and consciousnesses while also questioning the roles they embody in their photographs; concepts such as identity, gender, and memory become subjects of inquiry.

Virginia Woolf seems to be a huge inspiration for you. When did you discover her, and what about her appealed to you?

Virginia Woolf's works' fusion of different times, places, and forms is one of the most significant influences on me and my work. Her departure from conventional forms and the dissolution of form boundaries resonate in my own work through the use of materials from different times, places, and forms. The juxtaposition of lace, photographs, colors, light, and shadows mirrors the unexpected appearance of punctuation marks or spaces in Woolf's works.

I've been making artwork with lace and handicrafts made by my mother and family for a long time. I originally encountered these laces in my mother's trousseau. In Turkey, the mother prepares a young woman's trousseau before her marriage. Tablecloths and doilies are common examples of handcrafted items in this trousseau. My mother arranged a lace-filled trousseau for me to decorate my home. I can say that I'm part of the final generation to carry on this tradition.

As I already stated, when I discovered these laces, I stared at them for hours and days. Throughout this procedure, I continued to admire Woolf's novels, and I noticed a connection between Woolf's snail metaphor and the laces. The snail carries all of the earth's knowledge inside its shell and displays it as trails and voids, similar to how lace transforms into the female body. Embroidering lace requires days of labor, and when you spend so much time with a material, it eventually becomes a part of you. Lace, in my opinion, are objects that have become a part of every woman's biology. I can perceive women's consciousness and recollections in the patterns, voids and lines of lace. I believe this has a profound impact on me.

We met at the Supermarket Art Fair in Stockholm. The theme this year was Dream On. You highlighted a subject that usually emerges in your work: migrant families.In contrast to previous works, you only portrayed their body shapes rather than their faces. What has changed? Also, how do they fit into the Supermarket's theme? What are their dreams, and what are your hopes for them through your artwork?

At the Supermarket Art Fair in Stockholm, I showed my work "Life Among Us," which consisted of six pieces. I used the free-hand embroidery technique, drawing inspiration from images of Turkish immigrant families' homes in Germany.

However, as you indicated, I represented the families in silhouette form to emphasize the "migrant home." This time, I tried to focus on the particular lives and experiences of migrants rather than the experience of being a migrant itself. How do we create spaces where we feel like we belong? What cultural objects from our own memory do we bring to these homes to create a sense of belonging? How does a home filled with belongings from two cultures turn into a "nest"? I critique the current migrant policies in Germany and around the world, which increasingly tarnish individual experiences by treating migrants merely as a group of people. The issue of migration is very weighty and significant, yet I approach it delicately by working on a material that is extremely fragile. The result is a form that seems to hover between sleep and wakefulness. Neither here nor there... A dream to find one's own trace.

Your drawings are generally filled with people, but there is another subject that emerges frequently: flowers. What is the meaning behind the symbolism of all plants?

The flowers I use, coupled with the soil, symbolize a memory linked to local culture. In addition to the photographs, they provide conceptual and formal support for one another. Each plant has a unique name and meaning based on its region. These plants remind us of the soil, belonging, and roots that are established along borders.

This interview finds you at a residence in Turkey. In what ways do art residencies help you? Could you tell us a little bit about what you are working on there?

The story begins when you leave your current location, and its significance changes as you move. Questions arise in all geographies, and the story is enriched by the cultures and experiences of other geographies. Women's handiwork varies by area, and I enjoy observing the differences and commonalities. This year, I will participate in an artist residency program in India, where I will extensively examine women's handicrafts and textiles in a geographical region known for its diverse cultures. I am quite excited about this.

The artist residency experience is unique; it enables you to discover and experience things that you can't find in books or on the internet. It expands my comprehension of art and shifts my perspective. I attended the Artist Residency Program (PASAJ) in Istanbul alongside Nazlı Moripek, a fellow artist who shares my perspective on art. Our goal was to do a collective study. We investigate themes of preservation, conservation, and protection by examining cultural and historical talismans' formal manifestations and symbolic implications. Additionally, we focus on historical and cultural rituals created by women and characterized by migration movements.

Please share where our readers can learn more about you and your art.

I'm making efforts to maintain my website up to date, and I'm also very active on Instagram. You may follow my current shows and the work I create on social media.

Thank you for allowing me to look at myself through your questions.

Thanks for this wonderful interview and these wonderful unique pieces of artwork. Gozde touched my heart and the memories of, once upon a time, wonderful handcraft.