The Power of Transformation with Selma Selman

A conversation with Tarantula: Authors And Art's Inspiration for February, Selma Selman

“Dear Omer,

Every time I miss a train, it takes me to the path ahead of time. Then I imagine I'll meet you in some cold trains full of colonized people - we don't understand the white man's language, we have to be quiet. That's what they told us. The trains are full then empty like my bed last weekend when I had a threesome. I travelled for 12 hours in one day.” Artist Selma Selman uses her lyric performance on Instagram to write to a fictional character.

Addressing topics like labour and economy, touching on femininity, patriarchy and fluidity of identity, she states that the core of her practice is transformation. She transforms scrap into value and teaches her community how to extract gold from the discarded motherboards in a non-toxic way.

Selma Selman is of Romani origin, born in the small village of Ružica near Bihać in Bosnia and Hercegovina. Growing up with a long-standing tradition of reusing and recycling scrap metal and other materials, a practice that was only recently discovered and valued by the first world, she includes it into her art practice with the assistance of her family members.

She earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Painting Department at the Banja Luka University and graduated , with a Master of Fine Arts in Transmedia, Visual and Performing Arts from Syracuse University in New York. She continued her schooling at Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam.

Apart from being an accomplished artist, she is also an activist who empowers Romani girls and supports their education through the organisation Get The Heck To School, which she founded.

Sandra Vitaljic: What brought you to art?

Selma Selman: Ever since I can remember, I wanted to become an artist. My relatives went down that path before me, and I had the privilege that my teacher, Dragica Biukovic, was always there for me to "push" me further if I faltered. She also bought my first painting. Art opened a new perspective for me. With artistic work, I reclaimed my freedom, privacy and my ‘self’.

How did your family react to your choice to become an artist?

I grew up in an environment where a girl’s life path is predetermined. They should marry and devote their life to creating a family, but I went in a different direction.

At first, I painted on commission, and my father served as a sort of manager. I produced many landscape paintings because people in Bosnia are in love with their river Una, animals, etc. Earning money from my artistic work and receiving support from other strong women in my surroundings, such as my former art teacher in middle school, convinced me that I should pursue this path. It wasn't easy. One of my first works. “I will buy my freedom when” is about that. I bought my freedom with success that transcended the boundaries of my environment, and it seems to me that even today, I am still in the process of redemption. Today, they are proud of me. I am some sort of celebrity in my community.

A few of your works are dedicated to your mother. Tell us about those projects and the need to tell her story.

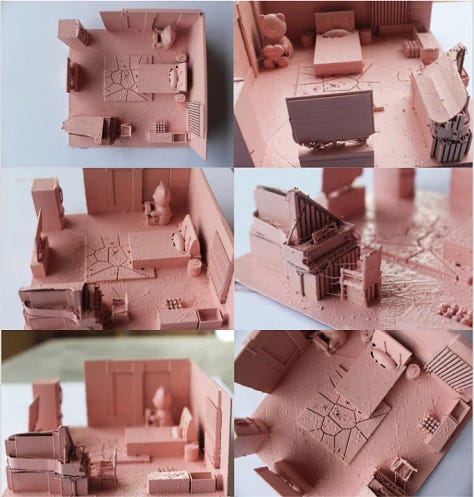

My mother and I have a very close relationship. She had a very different life path than I did, and she did not have an institutional education, but I consider her to be the most educated and smartest person I’ve known. I’ve learned a lot from her. She got married very young, before the breakup of former Yugoslavia, and after the war, she found herself in a newly formed country with no papers or citizenship. The work Salt Water at 47 tells that story. After a long battle with different paperwork, I filmed my mother’s first encounter with the sea, which was the first time she had left the country since her marriage. A Pink Room of Her Own represents an intimate relationship of mutual help between the two of us. My mother’s mindset and her life story gave this work a dimension of sublimity and humanity, which is exactly what she tried to convey to me through all the time I spent with her. By chance, I was able to fulfil her wish for her own room where she could spend her time. My mother is today's Virginia Wolf, and I just realized it.

There is also The Motherboards cycle, which reveals our bond in a subtle, more abstract way, among many other pieces. I can only thank my mother for giving me that unconventional knowledge that I value the most.

In your performance "Mercedes Matrix" you involved other family members. Can you tell us more about this project?

Due to the ongoing economic crises of Bosnia-Herzegovina, it is incredibly difficult to organize an adequate income, especially for Roma people due to a lack of education and discrimination – they live without government assistance. With my family, I performed “Mercedes Matrix,” where I used art to translate labour's value into art. In this work, art becomes a tool to question the labour of my family and my own labour as an artist. The same acts of labour which are performed are simultaneously undertaken for my own survival as well as for the survival of my family. The mechanism of these artworks transforms my parents' living reality and the possible function of art by fusing the work and reward of labourers and artists. My family transforms scrap metal into a valuable resource for survival. Their everyday survival depends on this exact same labour, with metal and motors sold in recycling centres. When this labour is recycled back into the domain of art, it gains value as artwork and demonstrates art's ability to transmute value, just as my family transmuted the value of scrap metal as a means of trade, demonstrating the equal potential for transformative activities in anybody.

In your multimedia works "Platinum" and "Motherboards", you transform scrap into something society sees as valuable. Can we read this work on a symbolic level?

These works express my questioning of the established norms of worth to different extents. First and foremost, as in my previous works, the question of labour (from stigmatized labour to prestigious labour) is followed by the question of wealth. My mother taught me that having a wallet gives you power and that having your own money makes you an independent person. I learned how to make gold via a non-toxic method known as “cupellation,” and I will pass that knowledge on to members of my community. The process of extracting gold from motherboards (the motherboard provides connectivity between the hardware components of a computer) gives this work a compelling, intimate context and highlights narratives of the tradition in which I grew up. Gold is important in the Roma community in the same way that it is the symbol of power and prestige in the Western world, and we will not be truly free until we are worth more than it.

The topic of transformation is noticeable in all your works: transformation of value, fluidity of identity, and transformation through labour. Can you explain why transformation is so important to you?

Transformation is at the core of my practice: scrap metal into gold, stigmatized labour into prestigious labour, and incapacity into invention. Even though Western society only recently discovered the benefits of recycling, Roma people have been collecting, reusing and recycling all kinds of materials, especially scrap metal, for a century or so. I have fully accepted this principle of sustainability because it does not only apply to the material sphere. The desire for self-sustainability pushes me forward to point out problems and cry out for change.

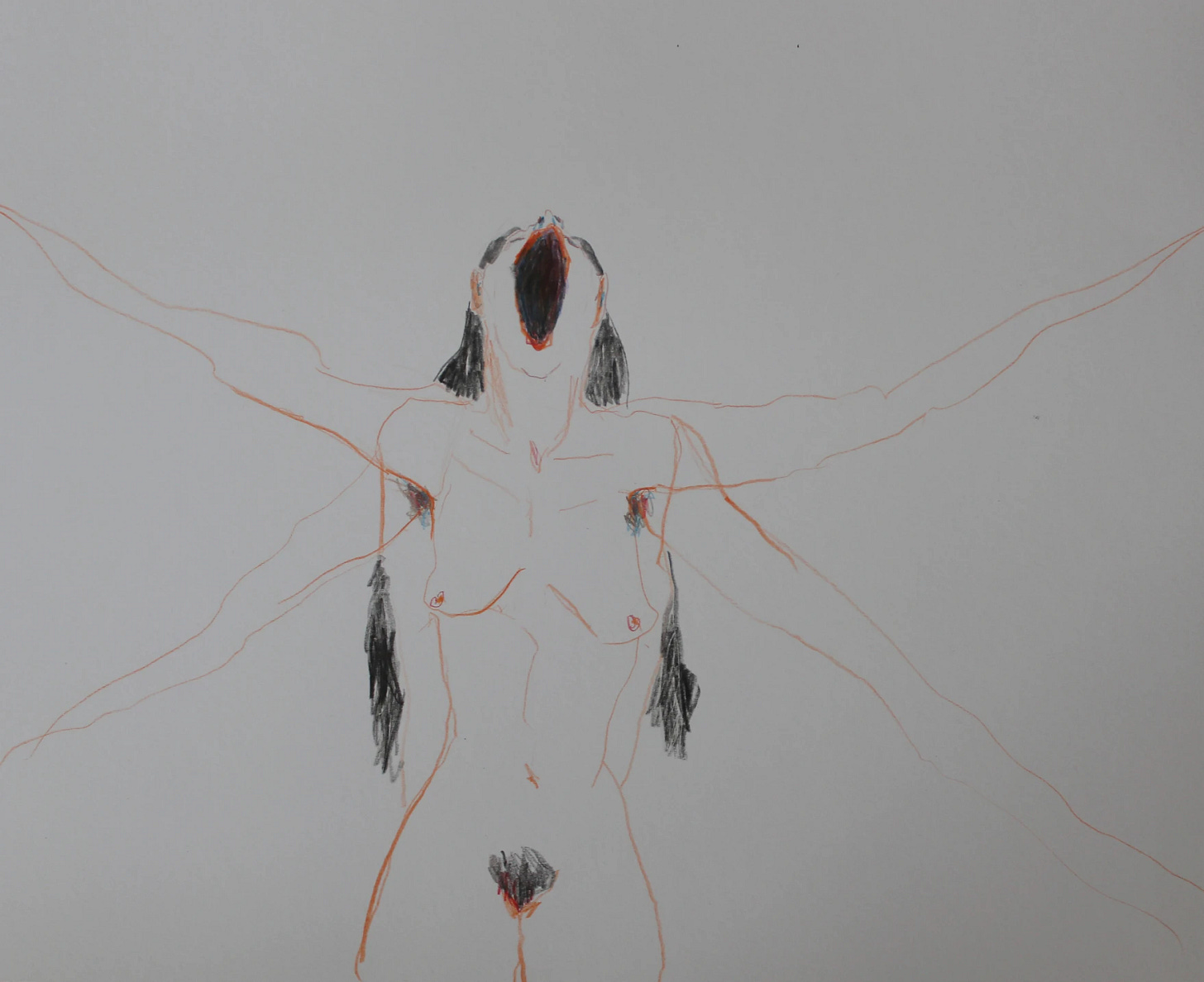

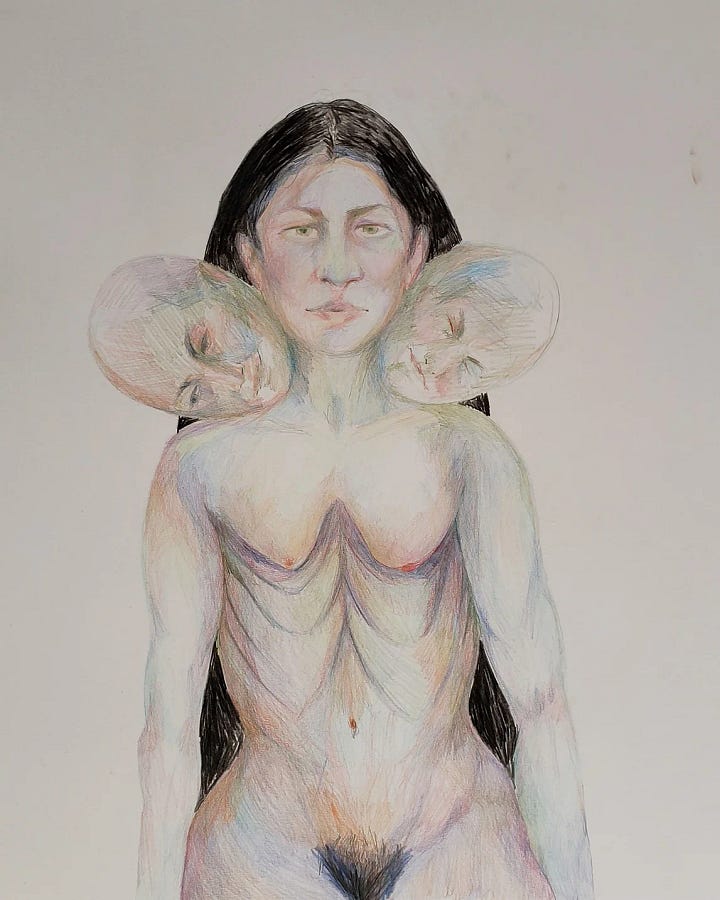

Can you explain the term "Superpositional Intersectionalism,” which stands as the title of your drawings?

“Superposition” is a term borrowed from quantum physics that defies the ability to exist in several states at the same time until measured. Intersectionality is transformed into an “ism,” implying a grand narrative about the interconnectedness of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender. This is a term I created to describe my almost dreamlike paintings, where I combined many aspects of my identity into one more or less abstract structure on paper.

You use social media for your performances. What is the potential of social media as a tool for artists?

I usually use social media to introduce my poetry. Social media gives us instant visibility and more direct communication with the public. This is why many of my followers get in touch with me after seeing an exhibition or attending performances. I love to encourage that intimate and direct way of sharing the experience because it is very important to me that my artworks understand and can relate to both individuals with and without the knowledge of the art world.

I was particularly drawn to your letters to Omer on your Instagram. Tell us more about that.

With my Letters to Omer, I share my most intimate thoughts and feelings with an imagined male individual named Omer. I tell him my secrets and desires and imagine what life with him may possibly be like. These are love letters to a non-person person, Omer, who is sometimes a robot and sometimes the system we live in. My letters are often very sad, scary and dramatic, and sometimes funny and confusing, but most people like them because they can relate to them, which is why I keep writing them because they are probably worth it.

You are also an activist and have established a foundation to educate Roma girls. What does your foundation do, and what challenges do Roma girls face today?

Get the heck to school/ Marš u školu is the project that I am very proud of. The foundation provides scholarships and daily lunches to over 50 girls in my village, and we’ve already received positive feedback. Those girls are now finishing their schooling, which was not the case earlier. They used to drop out of school as soon as they could start earning some money or getting married, but now they all aspire to be artists one day. That is a lot of pressure. I mainly find the funding because I support them with my own earnings and a few donations from honourable donors. Besides that, they each follow their own path. I am here to support them and to show through my example that they can achieve more with the right education, courage and perseverance.

What role does Studio Selma Selman have in your hometown? Do you perceive yourself as a role model for your community, and what responsibility does this bear?

As I mentioned before, I am somewhat of a celebrity for people there. They call me Tito. Given that Tito remains an important figure in former Yugoslavia thirty years after the country's disintegration, I embraced this and transformed myself into a superhero. They can see my successes, and many girls desire to follow in my footsteps, but there is also an assumption that I do not belong there. Because of my career in the West, I am considered a white woman there, which at times makes me sad. I don’t consider myself to belong anywhere.

You exhibited and performed in different places, both locally and internationally, from Pristina, Sarajevo and Belgrade to Kassel, Cologne, Amsterdam, Vienna and New York. How do audiences react to your work? Is there a difference in reading and understanding of your work?

An intimate relationship with the audience is very important to me, as is the audience’s ability to understand and experience my works the same way, regardless of prior knowledge. This is why I unabashedly presume that the reactions of the audience are similar. We can all agree on what is oppressing us; there is a little difference in the basic needs of those who live in the village of Ružica and those in New York. Some of them may have more advantages, but their desires are the same.

Do you face and recognize structural racism and discrimination in the international art world?

The art world continues to evolve. I am glad to say that I am also participating in that process. Although I do not want to be classified, my origin, the fact that I am a woman, that I grew up in a small community with little opportunity for manipulation in determining the next steps on the path to success, all had an impact on the initial attitude toward me and my art.. But, breaking already established norms has become a part of my existence, so now I feel only pride.

What are you working on right now? Where can we see your next exhibition/performance?

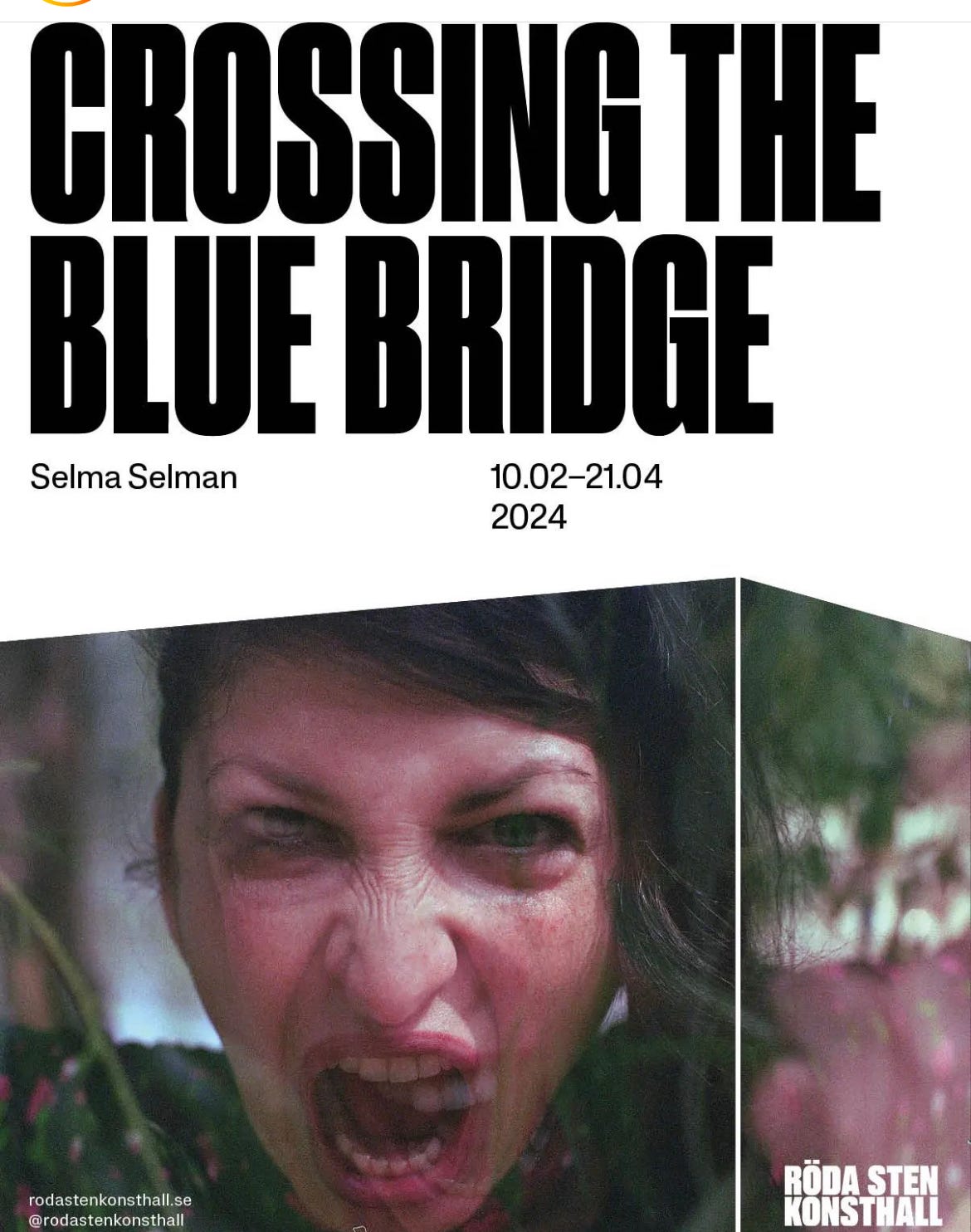

I recently closed my solo exhibition at the Gropius Bau in Berlin with a Letters to Omer performance, and I have already planned the whole year ahead. My first performance movie, Crossing The Blue Bridge, was filmed a month ago and will be shown in a solo exhibition at Röda Sten Konsthall in Göteborg, European Capital of Culture Bad Ischl Salzkammergut 2024, and Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. These will all be large-scale solo exhibitions, which I am very excited about, but there will also be many group exhibitions for which I will post information on my social media accounts, so if anyone is interested, more information will be available shortly.

For more information on Selma and her forthcoming events, you may follow her @selman.selma.

SELMA’S UPCOMING EXHIBITION

If you happen to be in Gothenburg, Sweden next month, join Selma at the opening of her solo show at Röda Sten Konsthall:

Crossing The Blue Bridge curated by @amilapuzic

Opening February 10

The opening starts at 12 p.m. with Selma Selman’s performance Superpositional Letter to Omer.

This will be followed by an introduction to the exhibition by Director Mia Christersdotter Norman, curator Amila Puzić and representatives of Röda Sten Konsthall’s partner institutions Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and Capital of Culture Bad Ischl Salzkammergut 2024.

At 2 p.m.you are invited to an artist talk between Selma Selman and Amila Puzić, the curator of the exhibition.

Refreshments and snacks will be served.

The exhibition is open 11 a.m.–5 p.m at the opening day.