“… It makes me cry. I want to talk about something I am not sure I can talk about. I want to talk about the inside from the inside. I do not want to leave it.

I am so happy in the silky damp darkness of the labyrinth, and there is no thread.” Hélène Cixous, The Book of Promethea

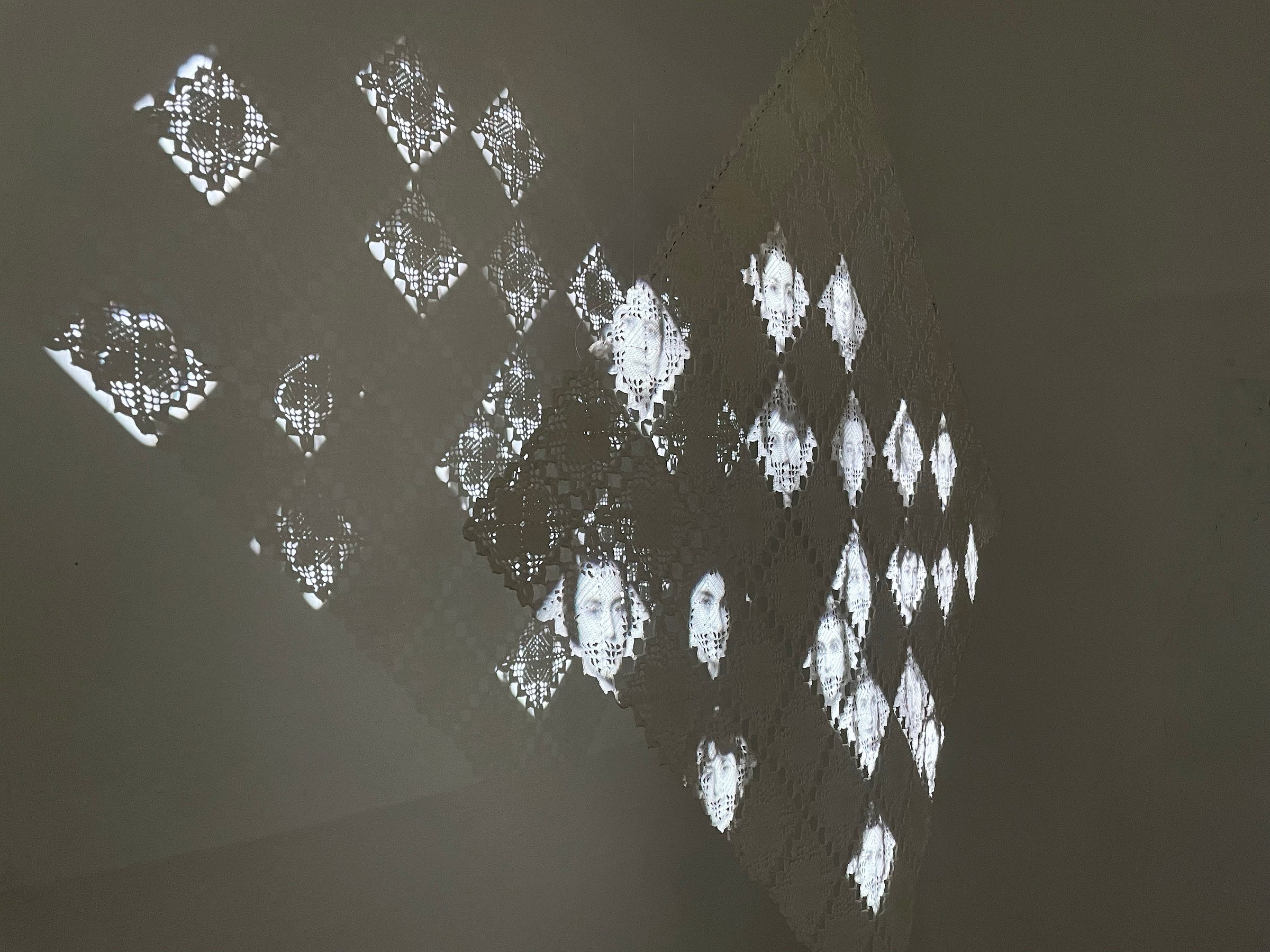

I’m attracted to artists who use thread as a medium, like this month’s featured artist, Gözde Ju. With a silent toil of the hand, the capacity to charge threads with emotional expressions fascinates me. Throughout history, intricate weaves have pushed humanity forward by acting as a powerful means for artistic, personal, political, and everyday stories as well as subversive reflections on society at large. What artists have always known intuitively, psychologists are now recognizing: we think with our hands as much as with our brains.

In his wonderous book “Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Future,” biologist and writer, Merlin Sheldrake, explores mycelia, the thread-like root structure of fungus. I’m not sure how much of an artist fungus is, but I wanted to explore the connection between the art of thread works and the expressions of mycelia. Through trial and error, mycelia have shown the ability to navigate through labyrinthic structures. Sheldrake suggests that certain fungus possess a form of intelligence. Other types of mycelia expand and grow; spreading across several kilometers. These laced networks show the ability to transmit nutrient signals, which serve root systems and ultimately connect trees located far apart across the forests.

In this associative comparison between the expressions of laced fungi networks and textile artworks, much of the above becomes applicable to the process of an artist’s mind and the resulting thread works. For instance, the desire to reach out, to connect, and to be a beneficial partner in a much larger structure. I can see the powers of an artwork acting in this benevolent, organic way. By their mere existence, mycelia threads possess the ability to feed and nurture other living entities. Is this perhaps its very reason to exist? Is that the potential of an artwork as well, as an innate, selfless, collaborative entity that gathers, connects, transmits, and feeds other vital forces into being?

“I am so happy in the silky, damp darkness of the labyrinth, and there is no thread," wrote Hélène Cixous. She emphasizes the contradictory feelings of being both lost and found, desperate while at the same time happy—the paradoxes of human life. The labyrinth she refers to, much like the intricate paths of mycelia, is a quest through the complexities of life. The lack of a “thread” suggests that there is no easy path and that we must navigate through darkness, uncertainty, and ambiguity. We may feel lost but are still happy to pursue our search and exploration.

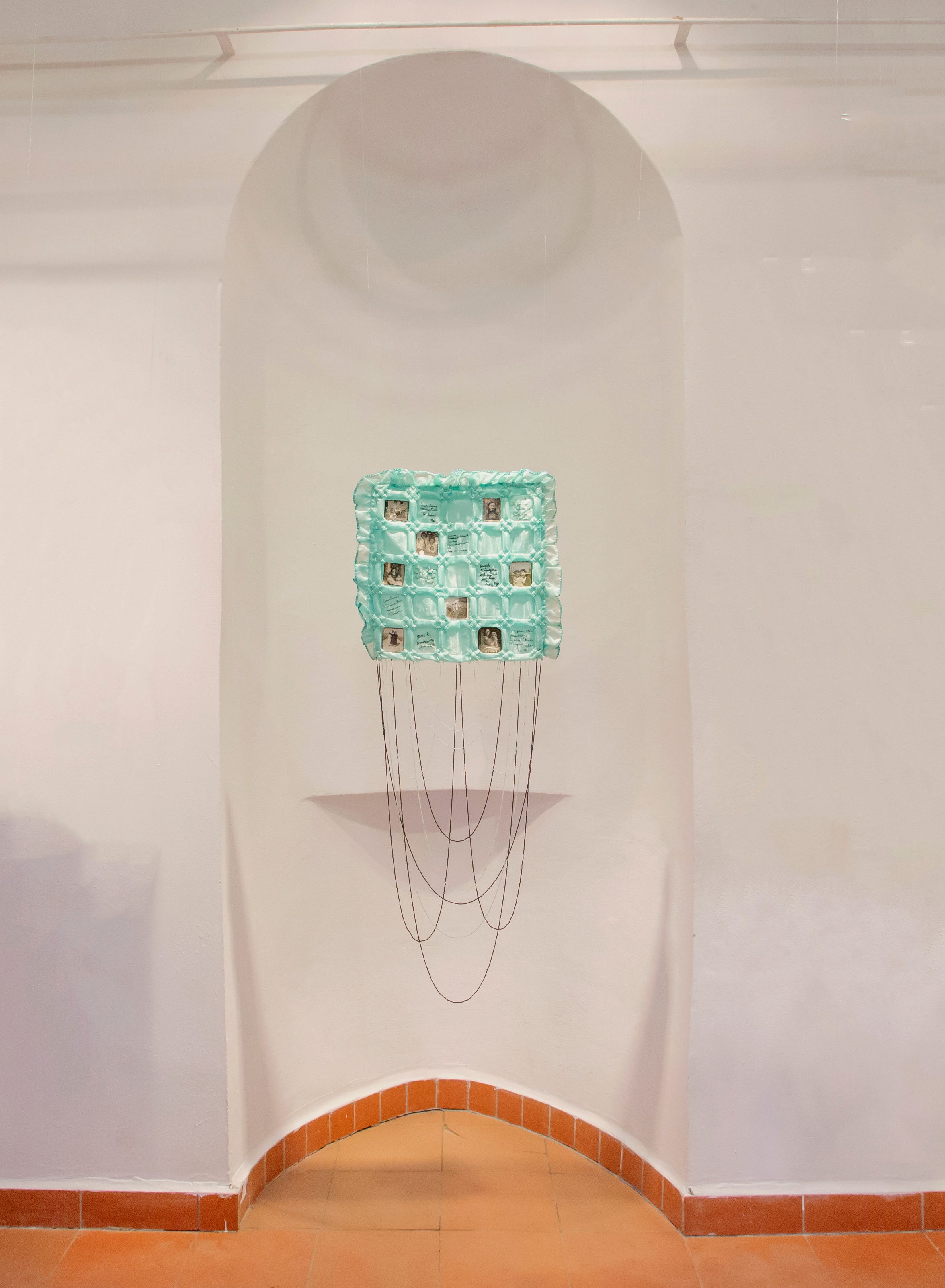

Techniques including embroidery, tapestry, and knitting have kept women’s hands busy throughout the history of humankind to provide clothing, narrative fabrics, home textiles, and more. Women performing these works were virtually invisible, taken for granted, and, for the most part, unpaid. Regardless, needle and thread have long been used by women to express stories about their lives, sentiments of belonging, conflicts, and love. In a Viking grave, for instance, some women were buried along with a kit of sewing needles. An item of great importance to carry forward into the next life.

In her book “The Subversive Stitch,” Rozsika Parker, a British psychotherapist, art historian, and writer, traces the shifting notions of femininity through embroidery from medieval times to today. Femininity is no longer shown as such, but rather through the skills of the embroiderer. Nor is it perceived as a wifely or domestic duty. Through the works of hands, Parker argues that women have always challenged the constraints that circumscribe femininity. Published in 1984, Parker concludes that despite the limitations of practicing art with needle and thread, “women have nevertheless sewn a subversive stitch—managed to make meaning of their own in the very medium intended to inculcate self-effacement.”

The process that Parker laid bare by unraveling women’s threads as a weave across history can be likened to Sheldrake’s mapping of the mycelia. Once revealed and viewed, both result in elaborate tracings of a labyrinthine expansion and growth process. Sheldrake says it best: “When I think about mycelia growth for more than one minute, I feel my mind expanding.” In my experimental attempt to combine the organic growing process of mycelia together with an artist’s use of thread, I have come to understand that there is an inbuilt yearning to communicate across the unknown and contribute to a system with selfless intent. When I observe women’s threads, I also feel my mind expanding.

About our guest writer

Cecilia Andersson

I studied photography in New York, yoga in India and hold a Master’s degree in curating from Goldsmiths, University of London. My specialization is in contemporary art where I have led artistic process work in an international context for over twenty years. I have curated numerous exhibitions in museums and public venues, conducted workshops, moderated panels and written extensively. Currently I’m head of department at Museum Anna Nordlander in Skellefteå and lecture at Umeå academy of fine arts in the north of Sweden.