Unveiling as Practice - Sculpting Layers of Life

A conversation with Tarantula: Authors And Art's Inspiration for April, Tove Kjellmark

Returning to Tove Kjellmark’s studio after some time, the air felt charged — not with noise, but with presence. A veiled figure sat on a wheeled platform in the center of the space: a woman carved in Carrara marble with golden veins, her body draped in stone fabric, arrested mid-transformation. The sculpture wasn’t new, yet something about it suggested she was still becoming. Tove had just unpacked her from a large crate, one of many that had recently returned from Seinäjoki Art Hall in Finland, where her expansive solo show The Horse, the Robot and the Immeasurable had ended its run. In 2022, the show premiered at Färgfabriken in Stockholm, and I was invited to contribute to Tove's book about her artistic process, which was launched at the exhibition. That was when Tove first reached out to me, and what began as a collaboration quickly became a friendship— one rooted in a shared obsession with horses, their emotional depth, and their role as gatekeepers to other realms. Like the shamans who once rode horses to journey beyond linear time and into the immeasurable, we too were drawn to their presence as messengers between worlds.

Tove describes the exhibition as being like stepping into her mind. “It was like walking into me,” she told me, “into all the fragments I was exploring in parallel.” Part working studio, part living archive, the exhibition brought together years of experimentation — everything from monumental bronze horses to hacked mechanical toys, intimate video works, and moments of failure laid bare. It was an invitation not just to witness an artistic process, but to wander inside it.

To me, Tove’s sculpting echoes the ancient myth of Pygmalion — the sculptor who fell in love with the statue he carved, a woman he then willed to life. That myth has echoed across time, inspiring generations of male creators — from classical artists to modern-day engineers designing sentient female robots, like in the film Ex Machina (2015). But here, the narrative is reimagined. Tove, as a woman sculptor, doesn’t seek to idealize or control. Instead, she enters into a material dialogue — sensing, listening, and carving with the intention to reveal the life already buried within. She doesn’t fabricate artificial perfection but coaxes presence from within the form, giving it a chance to breathe through her hands. To unveil, in her work, is to remember what was always there — and to call spirit back into matter.

At the center of this work lies a quiet, persistent question: how do we give life to something that is by all measures lifeless? And more importantly — what illusions must we let go of to witness the becoming of something truly alive? For Tove, this unveiling is not just an artistic method — it is a mission. It is a confrontation with death, a soft excavation of what lies beneath the surface. In its original sense, the word 'apocalypse' means revelation, not destruction. To unveil is not to end but to transform — to let go of certainty and allow something new to emerge from the once forgotten or from what we thought was lifeless or lost.

Tarantula Authors and Art: The Horse, the Robot, and the Immeasurable debuted at Färgfabriken a few years ago. Now that I'm looking back, what actually happened during that period? It felt volcanic, like you were being driven by something beyond yourself.

Tove Kjellmark: That’s exactly how it felt. I was a volcano. Every day I knew what I had to do — not intellectually, but in my body. I couldn’t tear myself away from the studio. Often, I stayed until one or two in the morning. I was in a state of flow that lasted for years. It was as if the works were insisting on being born, and I just had to follow.

Let’s rewind a bit. How did it all start, and how did you come up with the title?

Intuitively. The title came early, and it felt right immediately, even though I didn’t know exactly what it meant yet. I’m drawn to multi-layered meaning — I want the work to hold multiple entry points. I have been working with robots for years, exploring our perceptions of life in machines and how empathy can be elicited by the mechanical. What moves us when something "dead" begins to gesture like it's alive?

We talked a lot about life and death when I was writing for your book. You’re a sculptor obsessed with movement. Do you think motion equals life?

Absolutely. For me, movement is life.

So how do you bring life into a sculpture?

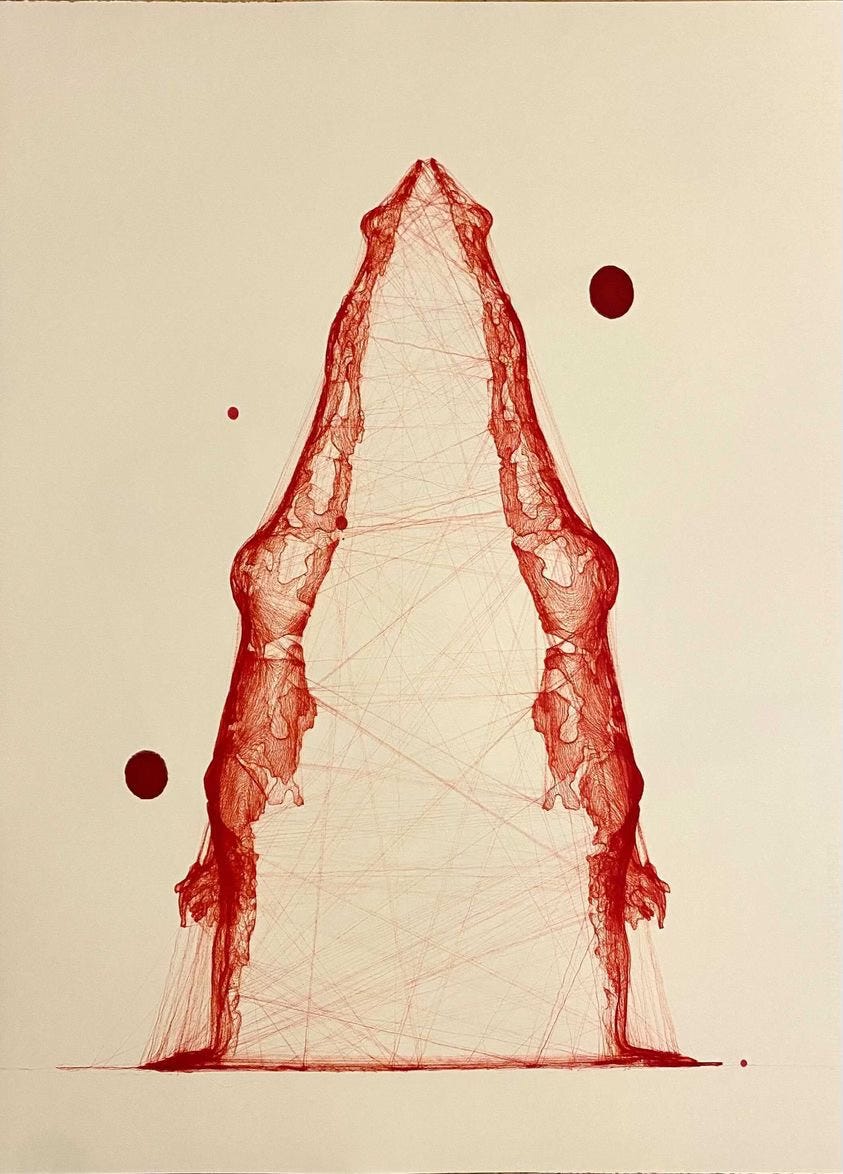

It’s about being present in the process. While shaping, carving or building, I have to stay open to signals, to surprises, to detours. Curiosity drives me. I never fully know what will emerge. Some days I have no idea where to start, so I begin by drawing. Eventually, I enter a space where I lose sense of time. Sometimes I’m in a trance. Sometimes I’m in the vast nothing. It’s a total openness. That’s where life starts.

There’s also something deeply personal in the act of stripping layers — I think a lot about how, early in my work with robotic animals, I would literally skin them, removing their fake fur. It was strangely emotional. Beneath the artificial coverings, I found these translucent plastic bodies — vulnerable, almost fetal. It reminded me of therapy, of peeling off emotional armor to reach something tender and real beneath. That experience deeply shaped how I think about unveiling—not as destruction, but as return.

Video: Tove Kjellmark, Dot Horse

You have this unusual ability to merge ancient sculptural techniques with high-tech tools — AI, motion capture, 3D scanning. What do these technologies give you?

I love working with things that I can’t fully control. Technology becomes a way to gather material, to catch what the eye alone can’t see. If I think about the viewer — it’s in their response that the illusion of life truly happens. If I feel something is magical, like these plastic robotic animals I once hacked and skinned, then usually others do too. I filmed myself interacting with them. Then I filmed from inside them — using spy cams. When they moved in herd, people began to see them not as toys, but as something alive. That tension fascinates me.

You also brought in the horse. When did that begin to enter your work?

Our horse, Noir, died around that time. It was devastating. He was such a powerful, gentle being. My daughter was heartbroken. Horses had always been part of my life, but never part of my art — until then. Suddenly, I realized how emotionally charged they are. There’s this tension between vulnerability and strength that stirs something deep in me.

It stirred something in many people. During the exhibition, visitors kept sharing personal stories about horses.

Yes. Horses awaken something. For me, horses have always symbolized freedom. As a child, the stable served as my sanctuary—especially during difficult times. When Noir passed away, I mourned him more profoundly than I have for some people I’ve lost. I think I began to understand him as a symbol, a portal. That’s when I remembered Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge—19th-century pioneers of motion capture. They were obsessed with capturing the movement of horses. That idea of translating invisible motion into visible form really resonated with me.

You’ve talked about the horse as both a free agent and a kind of machine. That duality runs through the exhibition — even in the title.

Right. The word "robot" originally meant "forced laborer." Horses have been both sacred companions and exploited workers throughout history. In my piece They Shoot Horses, Don’t They, I explored that contradiction. It was based on a real racehorse named Simba. He was put down because he could no longer perform. His body had become economically useless. I was granted permission to film his final moments using a thermal camera.

I projected that footage onto a concrete wall in the exhibition. You could see the heat — the life — slowly leaving his body. Evaporating into the stone walls. It was haunting but also beautiful.

That installation had such emotional gravity. It felt like a silent, sacred space.

I wanted to give Simba that — a moment of reverence. One visitor, a woman who had worked in palliative care her whole life, told me it was the most beautiful artwork about death she had ever seen.

You seem to be exploring what we might refer to as the veil — the delicate boundary between life and death, form and spirit, presence and absence.

That metaphor has become more and more important in my work. The veil isn’t just about death — it’s about transformation. About the layers we strip away to find what’s underneath. Even the process of sculpting, particularly in marble, revolves around the concept of unveiling. You remove material until something reveals itself.

Let’s talk about your marble figure — the veiled woman. She’s magnetizing. I can’t stop looking at her — it feels like she’s looking back at me from the end of time. You made her during your residency in Carrara, right?

Yes, in a tiny village near the quarries. It was my first time working in stone, and it was fascinating. With marble, you don’t build — you subtract. You unveil. The sculpture is already there inside the block, hidden under layers until the artist finds it.

The veiled woman is a meditation on the spiritual dimension, introspection, and making room for what can’t be named.

And Setare — my Akhal-Teke mare — played such a powerful role too.

Setare is like a spirit horse. Her pale, pearlescent coat, her light-blue eyes — she looks like she lives between worlds. When we brought her into the exhibition space, she seemed to merge with the walls. In the video piece, she was projected on a massive scale, ghostlike and glowing. She became a kind of gatekeeper — a being who dwells in the in-between.

When I was studying social robotics at KTH, I noticed something peculiar about the engineers I interviewed — it was as if they had a case of God envy.

I noticed when I visited KTH how they were obsessed with creating life-like entities, pouring years of work into building a robotic hand that could simply open a jar. Meanwhile, we already possess the ability to create life naturally — through birth. I began to feel that this urge to animate machines had less to do with utility and more with control, with demonstrating our uniqueness.

It echoed Pygmalion again — but a coded, circuital, sterile version of the old myth. That idea of “the in-between”—of” breaking the illusion of binary opposites like life and death, digital and physical, spirit and machine — it’s everywhere in your work.

It’s what I’m most curious about. Linear time, measurable reality —they’re comforting illusions. But life doesn’t work like that. Energy doesn’t disappear; it transforms. That’s what I’m trying to show. Not to explain, but to open a space where something else can be felt.

And maybe that’s the heart of your practice. Not to sculpt objects, but to sculpt experiences. Spaces for transformation.

Yes, to invite people to meet something — or themselves — without the usual armor. That’s the unveiling.

What are you most curious to explore next behind the veil?

I want to explore the wordless communication and energies between horses, humans, and other non-human others. This project still feels very alive —I’m not finished with it. But I needed a couple of years to live with the works that came out of this process. Now, new journeys are beginning. And it’s so joyful when we meet — every time we sit down, it’s like an explosion, a lightning bolt from a clear sky!

Yes! We were in such deep inspiration during those years — like we were being fed by some god-like source. It was a flood, and now you’re sitting on an incredible archive of all the material you collected.

There’s so much more to uncover. What I exhibited at Färgfabriken was only a surface scratch. We have so much left to discover about life, death, and the thin veil that gives the illusion of separation between us and other living beings and non-human others. I remember the woman who sat for a long time in front of the video work with Setare. Later, she told the guard, "Now I understand. I’ve been sitting here for over an hour. Then I turned around and saw the other visitors — and I realized, we are all the horse.”

Good luck with your new projects! If you would like to find out more about Tove Kjellmark , visit her website and Instagram page. You can buy Tove Kjellmark’s book – The Horse, the Robot & the Immeasurable at the following link.

About our guest writer Karin Victorin

Karin Victorin is a conceptual artist, writer, and researcher working at the intersection of art, technology, and transformation. With a background in anthropology, performance, and AI, she creates spaces for collective inquiry into identity, imagination, and the unseen. She lives with her Akhal-Teke horse Setare and continues to explore the thresholds between worlds — digital, organic, and spiritual.

Buy our print magazine by clicking on the following link

https://tarantulaauthorsandart.substack.com/publish/post/129709764

Looking at your horses made my heart pounding. As a small kid I had a dream: I saw myself walking in the grass along with a white horse.