What We Leave Behind

A conversation with Tarantula: Authors And Art's Inspiration for October Minna Kangasmaa

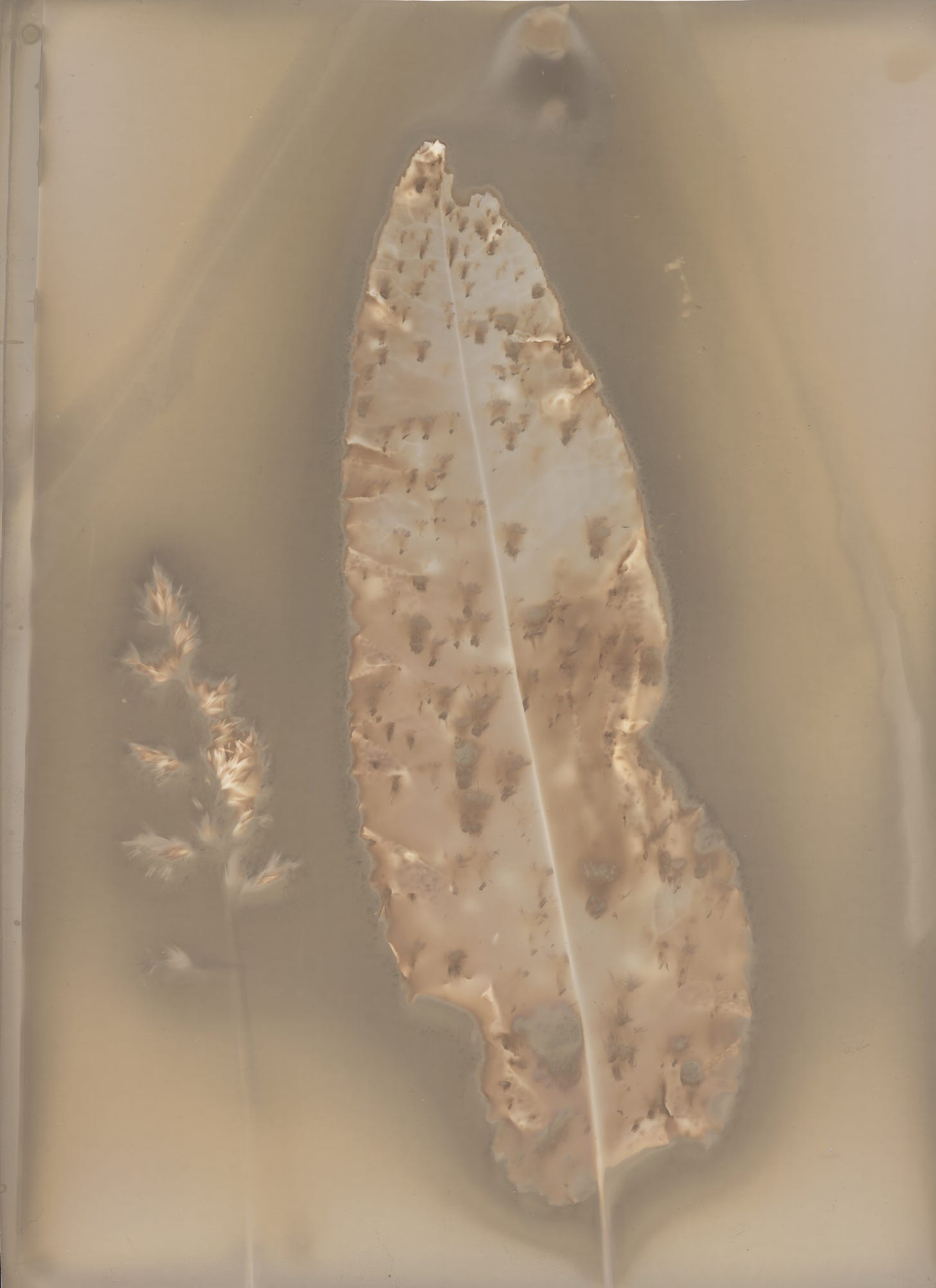

As I enter the ID:I Gallery in Stockholm, I discover delicate images on the wall, and I wonder if they will slowly fade away with time or remain fixed in their fragility. Images are photograms of plants placed directly on the surface of photographic paper. Each piece has a different format, hand-cut with raw edges. Each plate is unique, contrasting the indefinite reproducibility of the digital image and the predictability of the standardized photographic formats.

Henry Fox Talbot's photogenic drawings immediately came to my mind. Talbot truly believed that nature was writing on the surface of the photo-sensitised paper when he titled the first photo book ever published “The Pencil of Nature.” Since photography's invention in the 19th century, our understanding of it has expanded significantly, and we no longer regard it as a manifestation of nature or the bearer of truth.

Standing there, before those simple cameraless photographs made by artists Minna and Tuomo Kangasmaa my mind was unintentionally flapping through the image base imprinted in my memory bringing to the surface everything from Anna Atkins to lynching photographs, accompanied with an equally wide range of emotions. Even if photograms are the most basic type of photography, we are only able to perceive a reflection of our own culture and not the hand of nature.

Throughout her whole artistic career, Minna Kangasmaa has focused on the interaction between mankind and nature, employing a variety of techniques, materials, and approaches to explore this universal yet intricate interconnection. Her works also include concepts of transition, transformation and synchronicity resisting to be presented as completed and finalized work.

Tarantula: Authors And Art: You recently had an exhibition at ID: I Gallery in Stockholm. Tell us about Chiaroscuro, the project you exhibited with your husband, media artist Tuomo Kangasmaa.

Minna Kangasmaa: The story of the artworks in the exhibition at ID:I Gallery in Stockholm began in 2010, when media artist Tuomo Kangasmaa and I had parallel solo exhibitions at the Oulu Art Museum. At that time, we received three large rolls (60 m) of unused old analogue photo paper from the art museum since the museum no longer had use for it in the digital era. On the cardboard box of the rolls was written "last used 1998." We stored the rolls in our studio with the intention of using them someday. Then, we forgot about them for fourteen years. We dug them out again like old memories.

Our exhibition Chiaroscuro features plants exposed to direct sunlight outdoors. All works were handmade silver gelatin photographs created using the photogram technique. The photographs were produced without a camera, in a straightforward process, where the quality of the photographic material, the amount of light and the fixing chemicals of the images produce an artistic impression that is only partly controllable.

Throughout human history, plants have been depicted in all known ways: two-dimensional and three-dimensional, realistic and stylized, black and white or using color, symbolic and for identification purposes, scientific and artistic. We collected plants from partly planted cultivated areas and partly wild plants from wastelands. The plants we used were in different stages of their life cycle; some were fresh flowers full of chlorophyll, while others had almost withered leaves that were almost rotting. For us, the plants represent the northern time, which means a short summer with plenty of sunlight, but only for a short period of time. Our work adapts to this. Summer is an intense and dense time to make these photograms. Plants also react to the amount and quality of light in different ways. Like photographic paper, plants contain a light-sensitive pigment, leaf green, i.e., chlorophyll. The photosynthesis of plants is the dominant medium of the entire spectrum of life and the plants' creative interpretation of the sun. Only plants know how to turn light into food.

Interestingly, you connect light writing on a sensitive surface of the photo paper and the plants that use light to produce food for themselves. Were you inspired by living in the North, with its white summer nights and long, dark winters?

The northernness runs deep in me. My roots are in the North. When living in the North, changes of light during the year, with bright summer nights and dark winter days, is part of my every day. It's natural and I live with that. Still, it inspires me a lot.

It influenced the title of our exhibition and the series of photographs, Chiaroscuro, which comes from the Italian words chiaro, “light,” and scuro, “dark”. Chiaroscuro is an Italian term which translates as light-dark and is characterized by relatively sharp differences between light and dark. This kind of big difference in light and darkness is very familiar in the North.

Nowadays, Chiaroscuro is generally only mentioned when it is a particularly prominent feature of the artwork, usually when the artist uses extreme contrasts of light and shade as we have done in our photographs. Chiaroscuro can be also used to create a strong plastic, three-dimensional impression. This is also noticeable in our photographs.

By using expired photo paper, you are embracing serendipity and randomness since the result is only partly controllable. Do you usually work in that way?

In my artistic practice, I consider the potential of serendipity. In my work, I start with things that I want to explore through art. My artistic work is a search for a conceptually appropriate medium, technique, form or material. The external appearance of my works is always meticulously prepared, and they can be conceptual entities; despite this, the process of making them is very open and intuitive. I like that configuration.

Although I plan my work very far in advance, I always try to take advantage of serendipity. It means to me the ability to make unexpected discoveries guided by chance, as well as the ability to draw conclusions from noticing surprising things, even if my original goals were different than what I ended up with. The flexibility of thought helps me realize that what I have found is more valuable than what I was looking for in the first place, which gives me the courage to abandon the old plan and dedicate myself to the new one. From this point of view, serendipity is not about mere uncertainty or the unlucky or random nature of circumstances. I think it emerges through perceptiveness, attentiveness and vigilance. I dare to let chance lead me, usually in a subject area of which I have extensive knowledge, as I usually know how to take advantage of the opportunities that serendipitous discoveries present.

I noticed change is an important aspect of your work. In Chiaroscuro light changes photo paper during long exposures. In your installation Prima Materia II (2021) you work with a wall structure made from raw clay. During your exhibition in Copenhagen, the wall structure changed colour, cracked and even collapsed. Why is transformation/change in your focus?

Prima Materia is an installation about the changing states of matter and energy. The title is a reference to the formless matter that permeates all beings. The work depicts a chain of events that progresses through the material of the piece, leaving a memory trace. In this process, it balances on the interface of existence. The unfired clay in the work is a physical entity that embodies change by occupying an intermediate state between disintegration and construction. Clay dries, shrinks, cracks, and becomes permeable, giving rise to irreversible metamorphoses in the work. Clay tells about our connection with the soil and with the constant cycle of materials. Clay is a mineral material produced by geological processes, and it has been used by humanity since the dawn of time. I am fascinated by its physical properties. Clay is composed of minute grains of matter that are just 0.002 mm or less across; they give it plasticity and the ability to absorb dissolved substances and gases. Clay reacts intensively to environmental conditions; you might almost say it is alive. It is unpredictable in its motions, yet it seeks to return to its previous form as if it remembers. The history and time intertwined at its core both attract and touch us. Working in a manner that respects clay and space is a key theme in my practice. Raw clay reintroduces nature into the exhibition space, a nature whose presence and importance we sometimes forget. The work reminds us of the interdependence of nature and humanity, and of the fact that we can coexist if we want. Humans have always sought to change their surroundings; by building, we leave our mark on the environment. Mountains and rocks will gradually erode into stones, gravel, sand, and finally, clay which sinks into the ground, melts, and is reorganized. The cycle is slow, a process that takes hundreds of millions of years.

Your work often involves the interrelation between nature and humanity. Many of your works form a coherent whole under the title Systema Naturae. Could you elaborate on the concept behind this series that has been ongoing for many years?

I have been working with the series Systema naturae since 2007. The series Systema naturae is observations about the relationship between humans and nature, change, the material world, connection to the earth, transience and time - the interconnectedness of everything.

The word ‘nature’ is commonplace, but its meaning is becoming more challenging almost by the day – new ideas about nature reveal new aspects of ourselves, society, culture and history. In the 18th century, Swedish natural scientist Carl von Linné classified humans in his taxonomic system as one species in the order of primates. After the designation, he added the motto ‘nosce te ipsum’ – know thyself. Based on this motto, I have made a series of works that explore alternative ways to understand the planet as a meeting point for humans and non-humans. A key issue with this is the human capacity for empathy and how it might be extended to cover the entire globe. Our relationship with nature, including how we use limited resources and treat other people, animals, plants, and everything else on this planet – all this has implications for our present and future. Empathy plays a crucial role because it leads the way to a new kind of understanding.

In my work, I try to challenge our relationship with nature. I am convinced that there is nothing more important and urgent than monitoring the current ecological crisis. The pieces in the series reflect our age when human activity has fundamentally altered ecosystems and even the geological shape of the Earth. Plastic is one material that can be considered purely anthropogenic and whose impact on ecosystems we still do not know fully. When the organic blends into the synthetic, plastic becomes part of us. Does the merging of plastic into a permanent, inseparable part of natural systems make us aware of the problems in the concept of nature? What is nature when it is no longer nature?

You often collaborate and exhibit together with your husband Tuomo Kangasmaa. Can you tell us about how and why you work together?

I am interested in collaborating with other artists. I have been involved in several artist groups and art projects. In the autumn of 2020, I co-founded, together with my husband, media artist Tuomo Kangasmaa, an artist-run initiative called Art Hub Pikisaari in Oulu in northern Finland. Art Hub Pikisaari is an art project space and small-scale art centre on the Pikisaari island. Art Hub Pikisaari is located along the main thoroughfare of Pikisaari in an old log house in the former workers' quarter. The log building completed in the 1870s is one of the oldest houses built in Pikisaari. The mission is to create Art Hub Pikisaari, a place that serves as a hub for artistic collaboration that crosses geographical boundaries in the field of contemporary art.

What are you working on right now? Where can we see your next exhibition?

At the moment, I am working with the work called In Progress. In a way, it is both my first and latest work. The source material for In Progress comes from my old work from 1994. The artwork has been placed in the Saarela sculpture park in Oulu, where seven life-size plaster human figures have almost completely disintegrated over time. I have followed and documented the life cycle of the work. In the end, I have collected the last pieces shaped by nature and shrouded in moss that once represented the personification of the seven virtues. I have returned to the sources of my early work to reflect on what it means to be human at this moment. It has led me to multifaceted questions about faith, hope, charity, wisdom, courage, justice and reasonableness. In Progress is constructed from the remains of a decomposed sculpture and photographs, in which the past is present and what once was is still there.

It contains the proposition that the matter that surrounds us is not only passive, raw or motionless, but vibrant, transformable and non-static, actively influencing. The work addresses long-standing questions regarding the interconnections of everything in a timely way. By focusing on the material and its life cycle, I advocate for our commitment to a sustainable future. Quite often, the materials that surround us exceed the limits of the "sustainable" concept. It is that disturbing transcendence that brings the material world, which supports life in many ways, in focus and shows the materiality of art a new relevance.

The work’s title refers to an unfinished and ongoing process, which is now on display in my solo exhibition at Galleria Myötätuuli, Raahe Finland until November 24, 2024. The exhibition is produced by the Oulu Art Museum, the regional art museum and part of the Oulu Museum and Science Centre. In Progress is a satellite exhibition to the Listen to the Dust exhibition at the Oulu Art Museum. The themes of the Listen to the Dust exhibition arise from dust, specifically what we carry in our shoe soles. It also evokes the layers of time, memory and experience that we carry with us. The main question is what will we leave behind when we are gone?

Thank you Minna! You can find out more about Minna’s work by visiting her website or her Instagram page.