This month, we have a special collaboration with curator Lorena Parada from LA Art Stockholm, who introduced us to Edgar Jiménez, a Colombian artist who is our May inspiration. Parada invited Viviana Mejia, a Colombian writer and curator, to create a narrative for our second contribution this month.

Whether you are a regular or have just discovered Tarantula: Authors and Art, welcome. Why not consider subscribing?

“Es mejor ser rico que pobre,”[1] exclaimed renowned Welterweight Boxing Champion Kid Pambelé when asked, "Of all this that has been your life in boxing, what do you like the most?" These infamous words have resonated in the Colombian zeitgeist for decades, ever since the boxing legend uttered them. It’s a simple but powerful message, especially in a country where 19,621,000 inhabitants live below the poverty line.

Antonio Cervantes was born in 1945 in San Basilio de Palenque, the first free town in the Americas during Spanish rule. It was the first of the walled communities known as palenques, founded by escaped African slaves as a refuge in the seventeenth century. It is the only town that has survived until the present day and holds enormous cultural and historical significance. In San Basilio de Palenque, Cervantes lived a life with many struggles. He would wake up early to fetch water and plow the bijao leaves to wrap the cakes his mother made. He would cut a load of firewood to feed the wooden stove and sell fish door to door as he walked barefoot under the hot tropical sun. As the years passed, he made his way through life by polishing shoes and selling contraband cigarettes. Cervantes was full-blooded and contemptuous. Ready to start a fight and hold his weight. According to his first manager, Nelson Aquiles Arrieta, he was “lean like an eel and solid as a rock.”

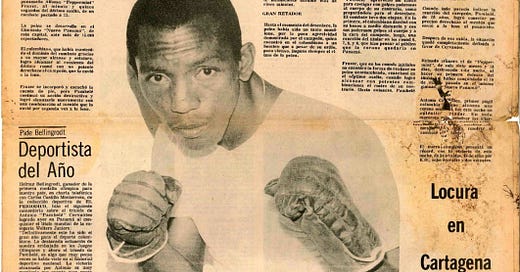

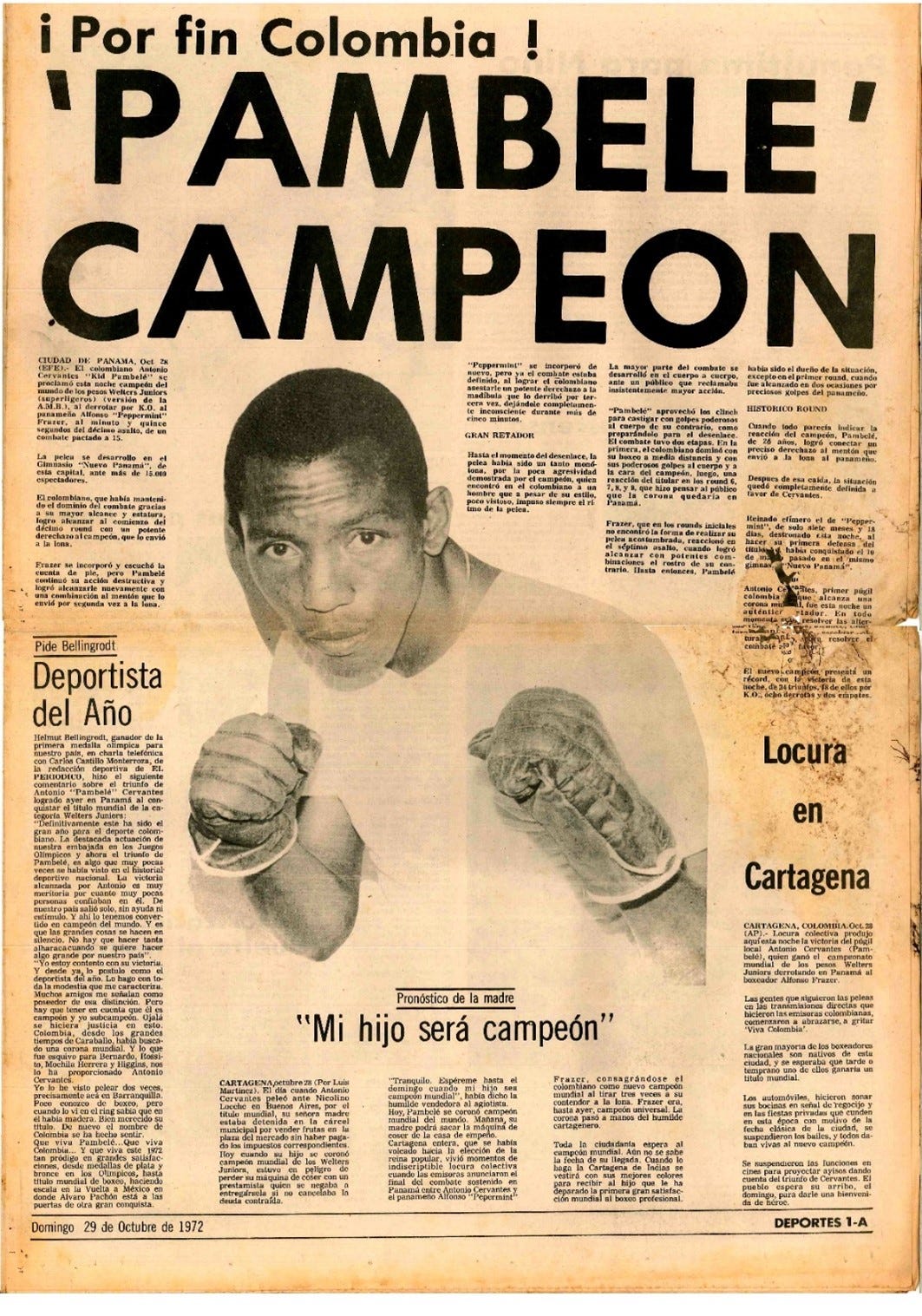

Like all boxers, he needed a recognizable moniker, and Cervantes asked to be called Kid Pambelé, after the famous Nicaraguan boxer of the same name. This was the nickname his godfather had bestowed upon him as a young boy. His first fight was when he was 18, and thanks to his lithe and sinewy physique, he moved swiftly across the ring. Pambelé’s interest in pursuing a pugilist career was sparked, yet he wasn’t a natural fighter. The up-and-coming boxer doubted his talent so much that he bet against himself and ultimately got caught, thus was fined by the Colombian Boxing Federation. In 1967, he fled to Venezuela to pursue his career, where his first manager thought he was good but not as good as he turned out to be. It took time to find his way in the boxing world. By 1971, Pambelé hoped to win his first junior welterweight championship but didn’t. However, in 1972, he was ready to take the world by storm and, against all odds, won his and Colombia’s first World Boxing Championship against the World Light Welterweight Champion, Alberto “Peppermint” Frazer.

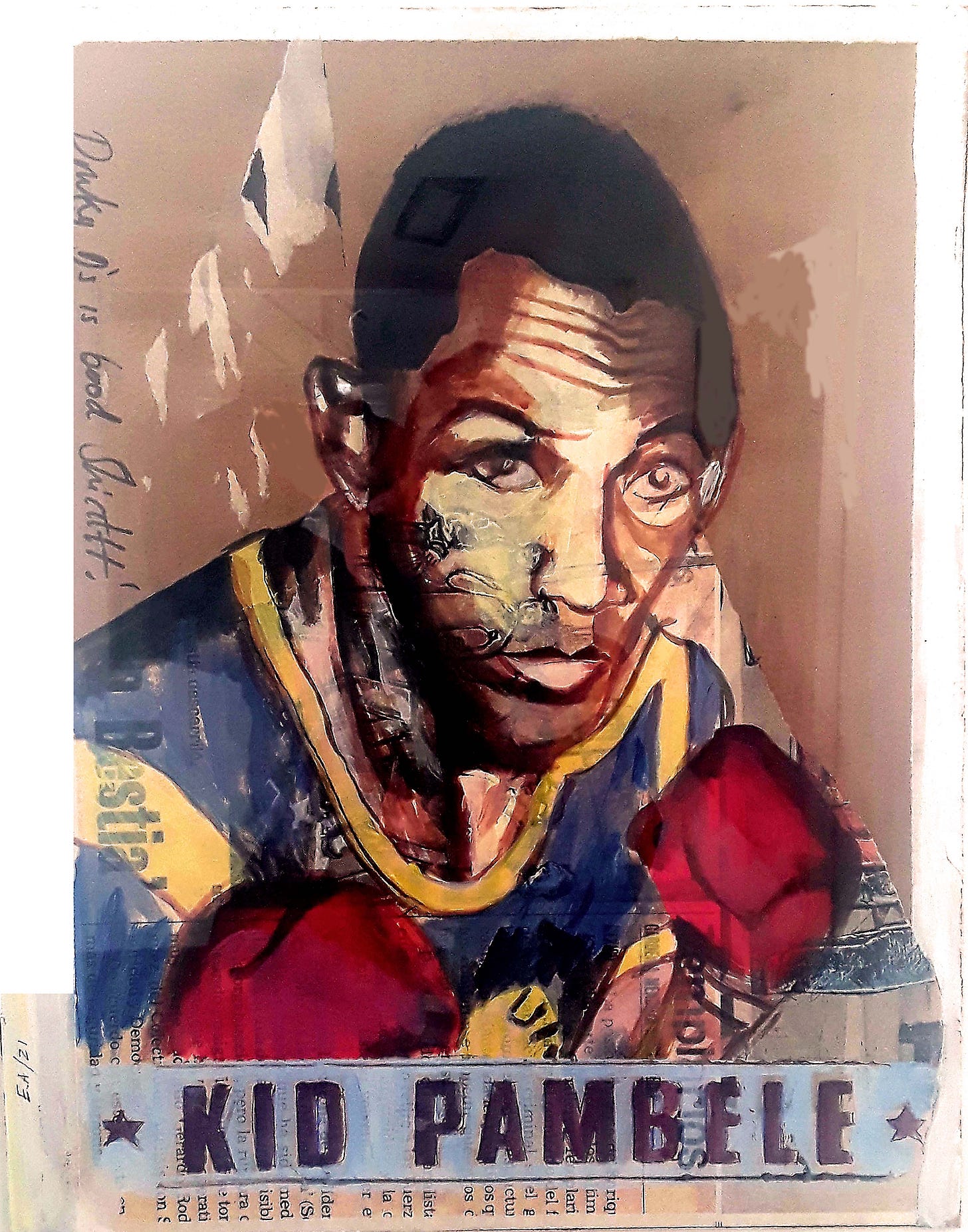

“Pambelé, el campeón”[2] read one of the many posters plastered in downtown Bogotá. Kid Pambelé is staring defiantly at the camera with his glove-covered fists ready to strike his first jab. The year is 1972, but I was seeing this in 2021. For a second, I was confused. Did Cervantes make a comeback, or was this a reissued newspaper headline, the type of gesture made by nostalgic boxing sycophants who claim that all the great ones were from the past? As I walked down the street, searching for answers, I noticed that more and more posters had turned into a pastiche wallpaper featuring Pambelé, tarot readings predicting a better future, and upcoming concerts. None of my theories proved correct. On the contrary, the answer was entirely unexpected. It led me to Édgar Jiménez, an up-and-coming artist from Cali, Colombia, who was bringing back the victories of yore to a cold and bleak Bogotá.

Jiménez intervened with those posters with a racist Jim Crow-era caricature of a black man plastered with vibrant colors. The juxtaposition of images was seemingly confusing, even contradictory, at first. But upon further contemplation and looking at the images, I realized his intentions. When Pambelé won the World Championship, his world changed. He was considered the most important athlete in Colombia in the 20th century and successfully defended the world junior welterweight title 18 times, ten of them between 1972 and 1976. To the victor belonged the spoils, and Pambelé became an overnight star. He was everywhere, with politicians and vedettes, invited to the best parties, and rubbing elbows with Colombia’s crème de la crème. This life of excess led to his experimentation with drugs and, unfortunately, a point of no return. Pambelé was welcomed at the Presidential Palace at the pinnacle of his career, and at his lowest, he was scoring drugs around its surrounding alleys in the city center.

Jiménez had found the newspaper announcing the victory in a second-hand street shop, triggering a critical memory. It reminded us how a black man had brought victory to our country; he had become a national hero, and now, he was just a recollection of the past. His artwork was a construction of memory and national identity and a reflection on a latent problem, neglected and lost in political discourse and aimless rhetoric. Jiménez’s use of a racially prejudiced image brought attention to a reality constantly ignored in our country: the racism that our Afrocolombian population faces on a daily basis. This is evident in the limited availability of better opportunities, income, jobs, land, and health care, amongst many other things. His wit is poignant, as his audacity breaks a fourth wall with the audience forcing them to think and reflect on the reality of discrimination and racism. Pambelé was a hero until he wasn’t, until he didn’t fit in, and he was just another black man aimlessly roaming the streets of Bogotá. Jiménez challenges that notion. He wants us to remember the champion, acknowledge a community, and have a long-overdue conversation.

[1]“Es mejor ser rico que pobre” translates to “It’s better to be rich than poor”.

[2] “Pambelé el campeón” translates to “Pambelé is the champion.”