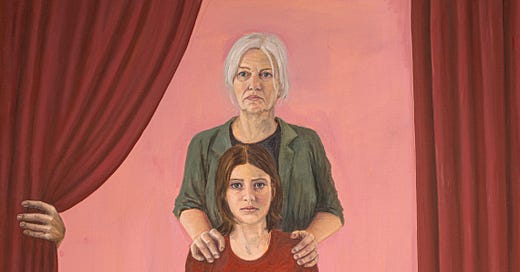

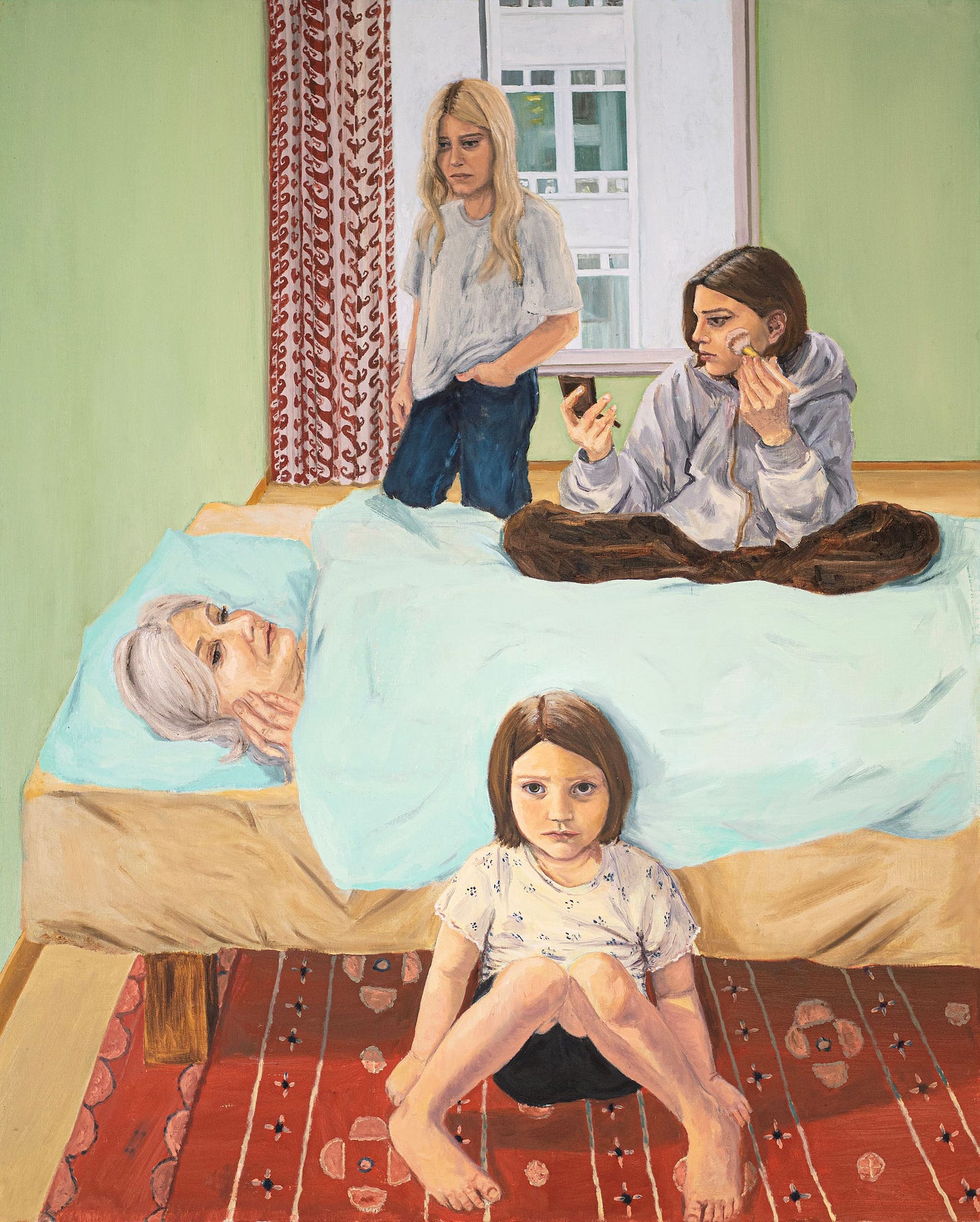

If you are a regular or if you have landed on Tarantula: Authors and Art welcome. This November, our inspiration is Swedish up and coming artist Viola Sparre. And today’s musings on the burden of old age inspired by Sparre’s work is written by our writer Maja Milanovic.

If a friend forwarded you this article, welcome; if you like it, share it or why not subscribe?

A book loomed over me from my mother’s bookshelf growing up, with its ugly khaki brown cover jackets featuring a centered thin-lined profile portrait of an old woman. It was written by Simone Beauvoir, who, I understood quite early on, was an author that belonged to the group of writers one must read to develop an intellectual mind. The book was about old age. Now, old age was something that scared me from very early on, ever since a few people casually mentioned when I was a child that I reminded them of my grandmother. At that age, when I looked up at my grandmother, I didn’t see her history, the mother of four of which one tragically died, someone who fought in a world war, someone who loved singing but ended a housewife, I didn’t see her story of matriarchy. What I did see instead is grey hair that was often teased by a comb to get volume, yellowish skin, her teeth that were left in a plastic cup each night of her bedstand.

Women of age were often portrayed in movies at that age as the wicked old witches. Their archetype embodied evilness, jealousy over lost beauty, eating young children to rejuvenate. Ageism was always hostile towards women. I was hesitant to reach for Beavouir’s book, which was entitled Old Age, but after my mother’s recommendation I opened the covers. Beavouir’s words spoke directly to my fears “Old people’s sadness merges with their consuming boredom, with their bitter and humiliating sense of uselessness, and their loneliness in the midst of a world that has nothing but indifference for them.” They are treated like the other, a burden: a heavy load. After a few pages, I closed the book forever, at the expense of never becoming an intellectual. But I knew one thing for sure, I was never going to become old.

It is probably not surprising to most that decades after forgetting about the book, I stopped posing for photos and started avoiding posting them on social media. What gradually began to happen to my face and body are the first indicators of getting forgotten - someone unwanted, silenced. My friends make me aware of this by spending money on endless hours of exercise, botox, and fillers. We are ageing despite all our efforts to look younger and to remain significant. And, as some of us have older children, some younger, as we postponed aging by becoming older mothers, I look at our children who still rely on us on a daily basis, fearful that one day they will forget about us or abandon us to elderly homes. Sandwiched between aging and not aging, right in the middle, I also look to the other side of the lifeline, at our parents who are obviously at that scary stage of life. Some fight it, looking amazing, yet their bodies silently suffer; others slowly losing their minds hoping that we, their children, will treat them gently and with dignity.

I grew up in a society where generations lived in the same house. The elderly helped with contributing to raising the children, cooking. My parents were the first generation to leave home and live their lives independently. So, I witnessed my grandparents aging from afar. As long as they were together, they still lived as usual, but the minute my grandfathers died, the grandmothers lost their voices. They were the source of the children's arguments on how to properly care for them. When memories, emotions, and divergent viewpoints collided, everyone became emotionally spent and somewhat more estranged from one another. I witnessed the aftermath and wondered how can this burden be handled when offsprings are falling apart?

Intellectualism has defeted us on this topic. Many philosophers have contemplated death, but aging wasn’t considered before Simone de Beauvoir. What looms over me these days as I gaze in the mirror at all the transformations that I have undergone in my bathroom in Sweden, a place I never imagined I would grow old, is the myth of Ättestupa, where the elderly were said to cast themselves off cliffs to unburden their families. I came to understand that Sweden starts getting ready ‘not to be a burden’ from very early on. They are raised to become self-sufficient and not ask for help. This can sometimes feel cold to foreigners and whole conversations are often erased because you are not supposed to complain about your ailments, but you also don’t want other people’s stories to ruin your day. And yet, what I am seeing these days, looking at the elderly in my extended family, is people hiding trying their best to stay under the radar and concealing their newly poor states, not to be sent to old people’s home - a kind of new ättestupa. I see my future in them and I feel anxious.

I now understand fully in my body that aging is inevitable. Every day, I am the youngest I will ever be as the days drift by. Perhaps I will become a burden, but was I not already a burden as a small child, a baby? Perhaps this concept of "burden" is a construct of a society that values productivity over connection. Living with these values, the future can feel bleak. And yet, as I wrestle with these fears, I find clarity in unexpected places.

Recently, I listened to a podcast featuring Swedish-Ethiopian, now American, master chef Marcus Samuelsson. I wanted to brush up on my Swedish because, as much as I have realized I will grow old, I also understood that Sweden will be the place where it happens. In the podcast, Samuelsson compared the deaths of his adoptive Swedish mother and his Ethiopian biological father. His mother spent her final years in a care home on Sweden’s west coast, a wealthy nation offering facilities to ease aging. Yet, she lacked stimulation. His father, meanwhile, lived in Ethiopia with his children, attended church, and continued his daily rituals until the end. Both passed away at 90, only months apart. Samuelsson reflected that his father, though living in a less affluent country, likely had the better life in his final days—surrounded by the familiar, engaged in the rhythms of life he had always known.

It seems that continuity is essential. Simone de Beauvoir recognized that societies often treat the elderly as the Other, exiling them from meaningful participation in life. But Samuelsson’s reflection suggests another possibility: a community where elders are not cast aside but remain woven into the fabric of everyday life. Parents, grandparents, friends, young and old—they don’t need to live together under one roof, but they should stay connected, engaged, and valued until the very end.

Perhaps this is what we must remember as we confront the transformations of aging. As Beauvoir warned, the loneliness and uselessness we fear in old age are not natural—they are imposed by a world that refuses to see the elderly as part of itself. If we take the time to truly listen, we might recognize their voices not as echoes of the past, but as human voices, still vital and deserving of a place in our shared present.

Beautiful Maja! Scary but beautiful!