If you are a regular or if you have landed on Tarantula: Authors and Art welcome. This February, our inspiration is Bosnian Romani artist Selma Selman. And today’s self reflection inspired by her work is written by our writer Maja Milanovic.

If a friend forwarded you this article, welcome; if you like it, share it or why not subscribe?

I stare at my overflowing trashcan of leftover food and plastic. Should the raw piece of meat be in it or in the compost? My building recently implemented composting as part of its new waste-reduction strategy. Was I supposed to recycle the little plastic covers?

A year ago, while attending the Supermarket Art Fair with Tarantula: Authors and Art, I witnessed efficient waste management in action. The fair's attentive staff, stationed at the front desk where various bins were strategically placed, enlightened me about Sweden's selective approach to plastic recycling. However, discovering that not all plastic is treated equally left me feeling even more perplexed.

I continue to look at the content of the small trash bag, and I am sure that despite it being paper, I shouldn’t recycle the filthy tissues on top of the garbage that contain my bacteria from a week long cold that just won’t go away. I close the bin before the bacterium spreads and I'm very certain that nothing in the bag is worth checking by forensics or archeologists hunting for evidence or valuable treasures. Happy that I at least consider sorting trash correctly, I instantly forget about it until a disagreement breaks out in the house about who will take out the trash or who has been responsible for the bags more frequently in a week.. Despite the massive amounts produced annually, we all want garbage to disappear as if it contains the deepest secrets of our humanity.

Just the other day, when I saw the garbage collectors early in the morning I came to a realization that they come so early, so that we don’t have to encounter them. If a certain small dog hadn’t barked at them because of their fluorescent vests, I wouldn’t have even noticed them. They help maintain this illusion that garbage is nowhere in sight: the dirt, the microorganisms, the stench can not reach or kill us.

In the Western world, we often go about our days without much thought given to garbage, despite being the largest contributors to global waste. Yet, for millions in other parts of the world, the dumping of garbage in landfills marks the beginning of their workday. For some, what we deem as mere "stuff" and leftover food, devoid of value, is the very essence of survival. It signifies life, not death. And for others, it can tragically lead to death due to hazardous working conditions and insufficient protections against toxic fumes. Regrettably, many of us fail to recognize their plight, viewing them as second-class citizens.

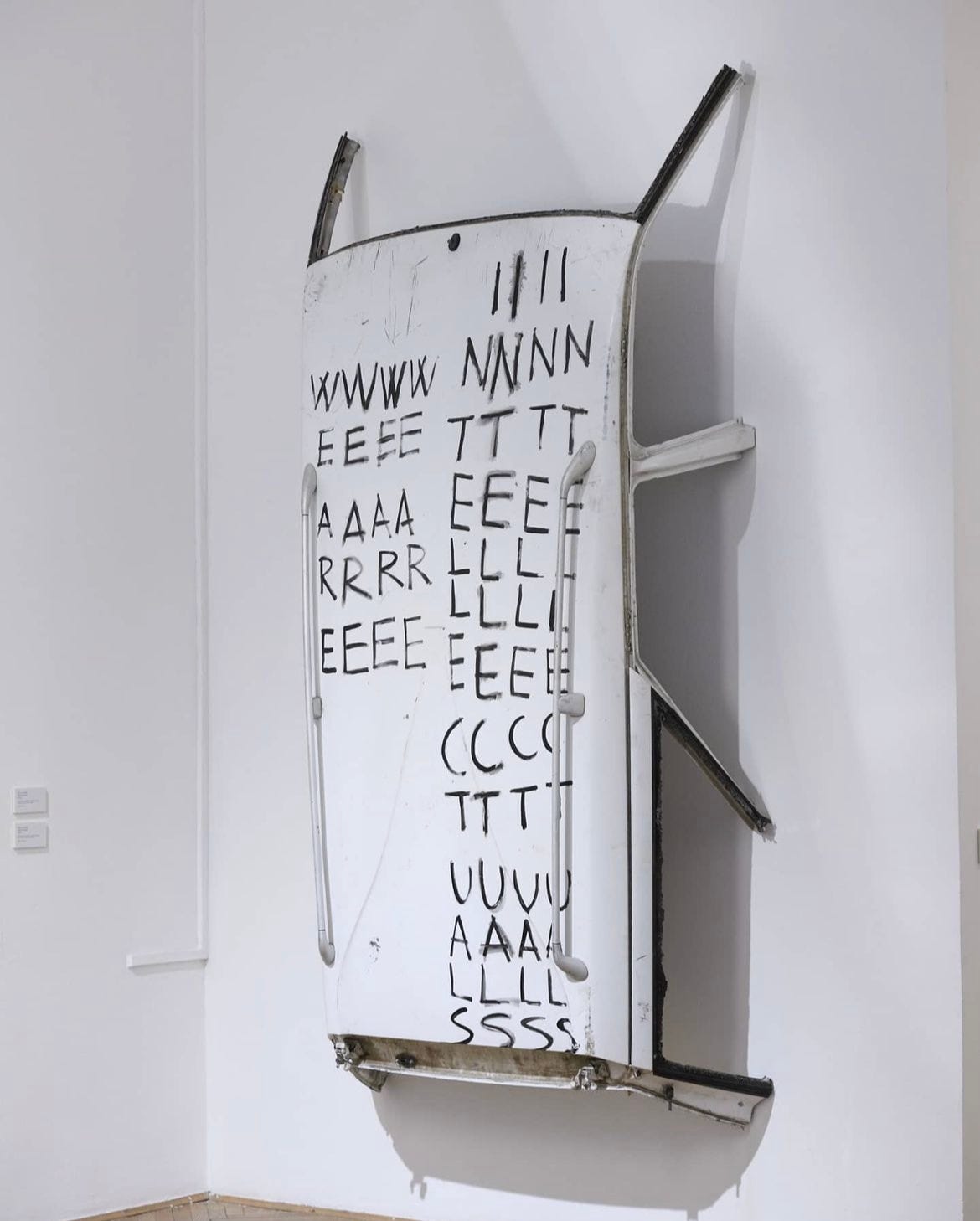

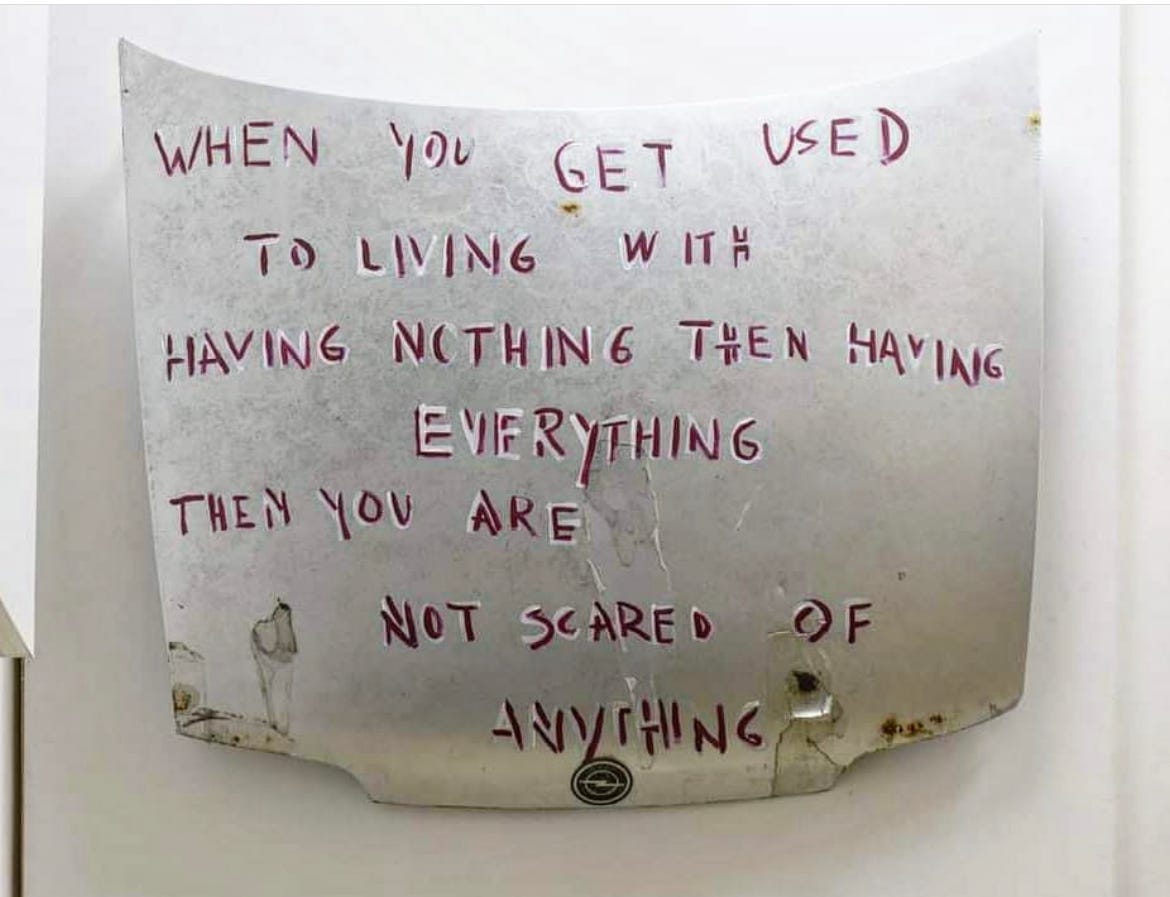

Selma Selman, the artist we featured this month, brings this to light through her work. Being of Romani descent, she takes her people's traditional labor of upcycling metal scrap to the forefront. Her artwork is powerful, strong, and beautiful. Sometimes heavy metal and sometimes Barbie doll. She questions why her people were shunned for recycling for over a century, and why we tolerate it now when she exhibits their work in our galleries. We leave her shows pondering about our own attitudes toward labor, prejudices, and our daily behaviours in terms of waste.

This stark contrast between the simplicity of waste disposal and the challenges of others who rely on it for survival forces me to reevaluate my beliefs and actions. It requires a thorough rethinking of our waste management systems, not just in terms of environmental effect, but also in terms of social equality.

To truly address the inequalities inherent in our current system, we must seek solutions that empower the disenfranchised and emphasize human well-being alongside environmental considerations. just then can we imagine a world in which waste management is not just practical, but also humane and equitable for all.